Chile Earthquake: Do Bigger Tremors Loom?

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Scientists had been waiting for this one.

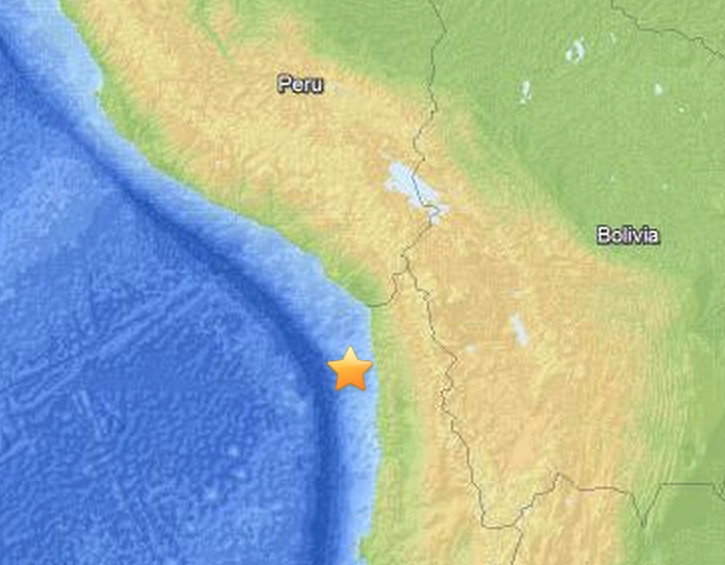

The 8.2-magnitude earthquake that rumbled off the northern coast of Chile on Tuesday (April 1) was located along the Pacific Ring of Fire, where plate boundaries grind past each other, producing tremors all the time.

But this particular quake struck smack in the middle of a 320-mile (500 kilometers) stretch of Chile's coast that had been alarmingly quiet for more than a century, said Rick Allmendinger, a geologist at Cornell University. [The 10 Biggest Earthquakes in History]

"The last earthquake in this segment was in 1877," Allmendinger told Live Science. That 19th-century temblor, estimated to have been 8.5 in magnitude, triggered a tsunami nearly 80 feet (24 m) high and caused fatalities as far away as Hawaii and Japan.

Tuesday's event was much less devastating. There were six reported deaths, a tsunami that rose to 8 feet (2.5 meters), and some landslides, power failures and property damage, according to the Associated Press.

Despite the decades' worth of built-up stress that was released in Tuesday's earthquake, there could be more energy stored along the plate boundary, ready to unleash aftershocks or even a bigger quake, Allmendinger said. It's possible that this tremor was a "foreshock," like the strong rumblings that led up to the 9.5-magnitude quake that ripped along the coast of southern Chile on May 22, 1960 — the biggest earthquake on record.

"The longer you go without earthquakes, the more likely it is that it will occur in the future," Allmendinger said. "That was the case in this particular segment."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Earthquakes greater than 8 in magnitude don't occur every year. Georgia Institute of Technology earthquake researcher Andrew Newman said they happen, on average, every 2.5 years.

The first signs of trouble started a few weeks ago, Allmendinger said. A magnitude-6.7 earthquake struck in the region on March 16, and it was followed by more than 60 earthquakes greater than magnitude 4, and 26 earthquakes greater than magnitude 5, according to the U.S. Geological Survey. But then the spot was quiet for about week before the 8.2-magnitude quake hit on Tuesday, about 59 miles (95 km) northwest of the port city of Iquique.

As a scientist, Allmendinger said he is interested in this pattern of seismicity, because it also has some resemblance to the lead up to the devastating 2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami in Japan.

"We may be able to learn quite a lot about it," he told Live Science.

Other researchers, too, are poring over data from Tuesday's event, looking for connections that could help them explain or predict the probability of big earthquakes. Newman, for example, said the tremor might demonstrate how interconnected earthquakes are in this region.

Tuesday's Iquique earthquake occurred about 13 years after a 8.4-magnitude earthquake struck immediately north of it, off the coast of southern Peru, Newman said. This pattern mirrors the 1877 Iquique earthquake, which occurred nine years after the 1868 Arica earthquake off the coast of southern Peru, thought to have been at least 8.5 in magnitude, Newman said.

In other words, one big earthquake could increase the pressure in another part of the plate boundary, triggering another big earthquake years later.

"These earthquakes seem to have really strong interdependence," Newman told Live Science.

Perhaps strangely, Tuesday's quake is the third greater than 8 in magnitude to occur on an April 1, but Newman said he doesn't make much of this April Fools' anomaly.

"Maybe Mother Nature's playing a joke on us," he said.

Follow Megan Gannon on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus