Icicle Images: A Cold-Weather Gallery

Three Icicles

Three icicles show how adding impurities (in this case, sodium chloride) to the freezing water creates ripples. University of Toronto physicist Stephen Morris and colleagues grew these icicles in the lab to examine their physics.

Natural Icicles

Icicles found in nature share this ripply surface. The ripples have a consistent wavelength of 1 centimeter, and researchers aren't yet sure why.

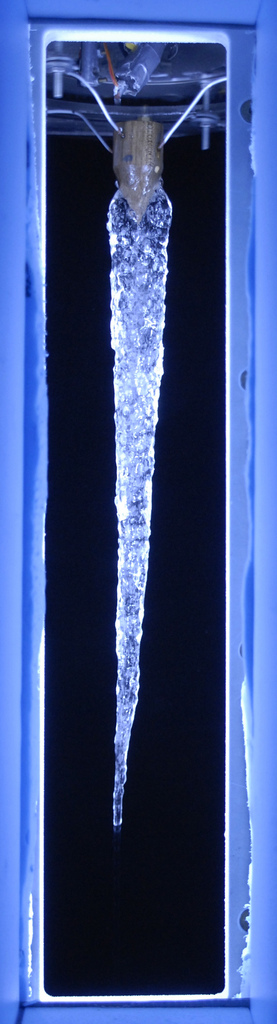

Distilled Water Icicle

A lab-grown icicle about 2 feet (65 cm) long made with distilled water. Without impurities in the water, the icicle is ripple-free.

Slightly Salty Icicle

Adding sodium chloride (salt) causes ripples to form on the icicle.

Very Salty Icicle

Adding more sodium chloride increases the ripple effect.

Clear Ice

Icicles form on a porch overhang. The physics of icicle formation is complex, according to the University of Toronto's Morris, because the water that forms icicles is supercooled.

Lab Icicle

Supercooled water forms "spongy" ice, so that not all of the water is frozen. Some is quarantined in tiny liquid pockets.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Ice Row

A row of icicles on a fence in Ottawa. These regular icicles form because of the natural instability of a water film on the horizontal edge of the fence, which creates drops a regular distance apart, according to Morris.

Church Icicles

Icicles line church eaves in Montreal, Quebec.

Icicle Melt

A drop of water falls off a melting icicle.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus