5 Scariest Disease Outbreaks of the Past Century

More people could mean more diseases spreading around the globe.

It is estimated that the world population will reach 11 billion by 2100, and one of the consequences of this population rise would be new challenges in controlling disease outbreaks, scientists say.

The population rise is also likely to boost the increasing rate of new infectious diseases caused by emerging viruses and drug-resistant bacteria -- a trend that has already been observed over the past few decades. Scientists are keeping an eye on new viruses that may cause the next pandemic, and are trying to find new cures for pathogens that have long been present in human history but are developing resistance to available drugs. [What 11 Billion People Mean for Disease Outbreaks]

Here are five closely watched diseases that have caused some of the deadliest or scariest outbreaks and pandemics of the last few decades:

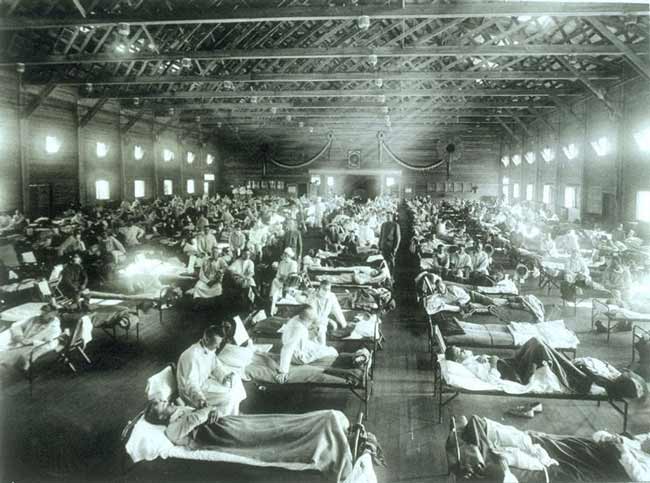

Influenza

From the gruesome flu pandemic that killed an estimated 50 million to 100 million people in 1918, to the 2009 swine flu pandemic that took thousands of lives, different strains of influenza viruses have caused some of the deadliest outbreaks of the past century. This group of pathogens is one of the most closely watched due to its enormous pandemic threat.

In its seasonal epidemics, the virus infects up to 15 percent of the population it hits. Annual epidemics are thought to result in between 3 million and 5 million cases of severe illness and between 250,000 and 500,000 deaths every year around the world, according to the World Health Organization (WHO).

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The ever-changing virus has gone through several major mutations in the past century and has been able to repeatedly spread to humans via domestic animals. Significant outbreaks caused by the virus include the Asian flu in 1957 and the Hong Kong flu in 1968, which each caused several million deaths worldwide, and the swine flu in 2009.

SARS

SARS, which stands for severe acute respiratory syndrome, is caused by the SARS coronavirus. It first infected people in late 2002 in China, and within weeks spread to 37 countries through air travel. The virus infected 8,000 people worldwide, about 800 of whom died.

Most patients infected by the SARS coronavirus develop pneumonia. The virus spreads by close contact between individuals, and is thought to be most readily transmitted by droplets produced when an infected person sneezes or coughs and the secretions are inhaled by another person. The disease can also spread when a person touches a surface or object contaminated with infectious droplets. SARS may also be spread more broadly through the air.

Scientists have traced the virus back to bats. It is thought that the virus found its way into the human population through livestock markets in China.

HIV/AIDS

Since its emergence in the 1980s, HIV has infected 60 million people and caused an estimated 30 million deaths.

Scientists think HIV, which stands for human immunodeficiency virus, made the jump from chimpanzees to humans sometime in the mid-20th century. The virus hijacks and eventually breaks down the immune system, resulting in a condition called AIDS (acquired immune deficiency syndrome). Without a properly working immune system, people with AIDS are left vulnerable to other, often deadly, infections.

The virus spreads through blood, semen and other bodily fluids. Most people currently get the virus by having sex with or sharing drug-injection equipment with someone who is infected.

In the United States, about 50,000 people become infected with HIV each year. At the end of 2009, 1.1 million people were living with HIV. Of those people, an estimated 18 percent do not know they are infected, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Globally, there were about 2.5 million new cases of HIV in 2011. About 34.2 million people are living with HIV around the world. In 2010, there were about 1.8 million deaths in people with AIDS, according to the CDC.

Malaria

Although it has likely been around since antiquity, the mosquito-borne disease malaria continues to pose a global problem. There's no vaccine for it, and in many parts of the world the parasite that causes it has developed resistance to a number of malaria drugs, according to the WHO.

In 2010, an estimated 219 million people worldwide were infected by the disease and 660,000 died. The disease is widespread in tropical regions such as Africa, Asia and the Americas, with about 90 percent of cases occurring in the African region.

Plasmodium, the parasite that causes malaria, gets into a person's blood through a mosquito bite and travels from there to the liver, where it sits silently and reproduces for days. Eventually, the parasites, hidden inside liver cell membranes, escape the liver to invade the blood, infect red blood cells, and disrupt the blood supply to other organs.

Tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) has been traced back as far as 17,000 years ago, but is still not entirely under control today. Caused by the bacterium Mycobacterium tuberculosis, TB is second only to HIV/AIDS as the greatest killer worldwide due to a single infectious agent.

In the past two decades, the TB death rate dropped almost by half. In 2012, 8.6 million people fell ill with TB, and 1.3 million died. More than 95 percent of TB deaths occur in low- and middle-income countries.

Although TB is curable, a worrisome form of TB that is resistant to most available and effective drugs (multidrug-resistant TB) is present in virtually all countries, according to the WHO.

Email Bahar Gholipour. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.com.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus