Crazy Cretaceous Find: Intersex Crabs

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

DENVER — It's a crustacean conundrum: Why did some Cretaceous crabs sport both male and female characteristics?

The answer is unknown, but new fossil discoveries reveal that intersex crabs were a small but persistent part of the population in South Dakota during the Cretaceous Period — and a parasitic barnacle may have been to blame.

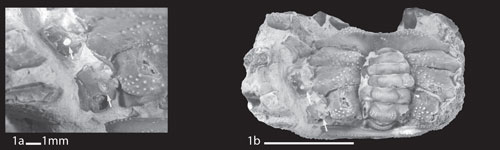

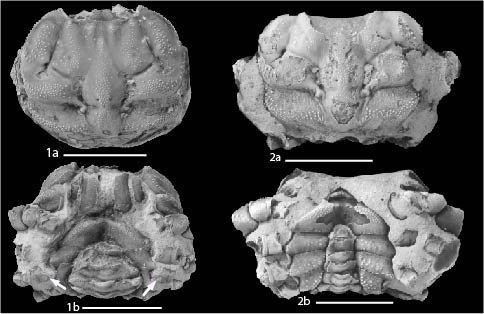

The fossils, excavated in South Dakota shale, are of Dakoticancer overanus, a quarter-size crab that lived about 68 million years ago. At the time, North America was split in half by the Western Interior Seaway, a shallow sea that harbored strange creatures like the toothy mosasaur, an apex predator that evolved from land-living lizards. [In Photos: Tiny Crabs Found in Fossil Reef]

The Dakoticancer crabs lived on the eastern shore of the sea, where roughly 2,500 fossil specimens of the species have been found. Gale Bishop, an emeritus professor at Georgia Southern University, excavated these specimens throughout the 1970s; the crabby collection now belongs to the South Dakota School of Mines and Technology. Such a large number of fossil crabs is "extremely rare," said AnnMarie Jones, a graduate student at Kent State University in Ohio who presented a new analysis of the fossils here last month at the annual meeting of the Geological Society of America.

In-between crabs

Jones is interested in population dynamics, an area that requires a large number of organisms to study. The crabs presented that opportunity, but she soon turned up something strange: A subset of the animals, about 1 percent, didn't fit neatly into male or female categories.

Instead, these strange crabs showed features of both. Typically, female crabs have broad abdomens and little openings called gonophores that release eggs on their third set of legs. Male crabs have narrow abdomens and gonophores to release sperm on their fifth legs.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The intersex crabs, however, were all mixed up. In most cases, they had narrow male abdomens with female-style gonophores on their third legs. Some, however, sported gonophores on their fourth legs, "which makes no sense," Jones told LiveScience.

"There's no modern analogy," she said. "It's incredibly frustrating."

Marine mystery

Unfortunately, none of the crabs' internal tissues fossilized, so there's no way to tell whether these intersex crabs had functioning reproductive systems, Jones said. It's also a mystery as to why the intersex crabs exist.

One possibility, Jones said, is that a contaminant in the water caused birth defects linked to the strange features. But if pollution was the problem, Jones would expect to see other fossil animals in the area with defects, and none have been found so far. A creepier possibility is that parasitic barnacles caused the strange sex characteristics. In modern oceans, parasitic barnacles can latch on to young male crabs, disrupting the glands that produce male hormones. The result is a male crab shaped like an adult female.

There's no fossilized evidence of barnacles on the Cretaceous crabs, so the parasite theory is speculation, Jones said.

"Hopefully, as research progresses, people will be able to find something similar, whether modern or extinct, and hopefully we'll be able to shed light on it," she said.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus