Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

A new, glow-in-the-dark antibiotic can reveal bacterial infections festering inside the body in real time, a preliminary study in animals suggests.

If follow-up studies show the technique is safe to use in people, it could one day help doctors identify bacterial infections growing on artificial knees and hips before they become unmanageable.

"You don't have to perform surgery, take a sample, cultivate the bacteria," said Jan Maarten van Dijl, a microbiologist at the University of Groningen in the Netherlands. "Now, with this fluorescent dye, we would have a tool that would allow bedside monitoring."

Infected devices

When patients complain of warmth, swelling and discoloration at the site of an artificial knee or hip, it can be tricky for orthopedic surgeons to know whether a bacterial infection is the culprit or if the reaction is just inflammation in response to a foreign object in the body.

If bacteria are involved, time is critical: Once bacteria gain a foothold on an implant, they can form a sticky biofilm that is hard to treat with antibiotics. [Video: Bacteria Weave a Tangled Biofilm]

"The biofilm is essentially a lot of goo in which the bacteria are encapsulated," van Dijl told LiveScience.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Often, infected implants have to be removed if the bacteria don't respond to antibiotics.

Van Dijl and his colleagues were using fluorescent dyes to track cancer inside the body when they realized a similar technique could work against infections.

The team fused a fluorescent molecule with the antibiotic vancomycin, which is used to treat infections of E. coli, Staphylococcus aureus and about 90 percent of the bacteria that cause implant infections.

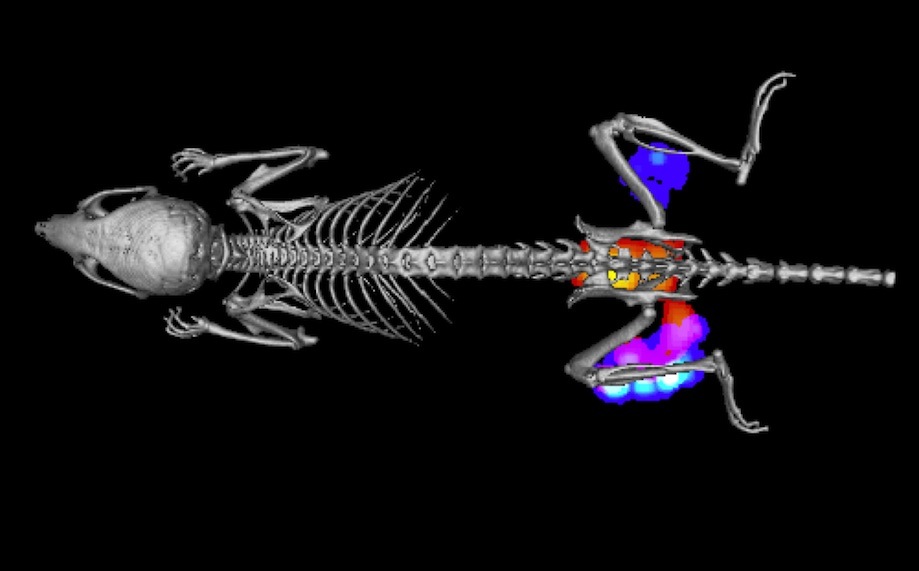

The researchers infected mice with S. aureus, and then shined a camera on the mice. The camera emitted a laser beam, which excited the fluorescent molecule, and allowed the researchers to see the infection as an extremely faint glow underneath the skin. [See A Video of Bacteria Glowing Inside the Mice]

To test whether the system could work in people, the researchers prestained a human ankle from a cadaver with the fluorescent molecule, and then detected its light using the camera.

The new technique could one day allow surgeons to quickly check for signs of infection in implants without cutting patients open. But it does have some drawbacks.

"It will only work as deep as the laser light and fluorescence can go through the tissue," van Dijl said, so very deep-seated infections could be missed.

In addition, the new molecule will have to be tested for toxicity and dosing in people. However, both the fluorescent molecule and the antibiotics have been used separately in humans for many years, so there is a good chance they are safe, van Dijl said.

The new technique is described today (Oct. 15) in the journal Nature Communications.

Follow Tia Ghose on Twitter and Google+. Follow LiveScience @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.

Tia is the editor-in-chief (premium) and was formerly managing editor and senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com, Science News and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus