Insect's Amazing 'Rubber' Made in Lab

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

A special type of protein enables insects to chirp, fly, and hop. Now, scientists have produced this same protein in the lab and say it could one day be used to repair human arteries.

The protein, called resilin, is like rubber. It can be squished up, storing energy for a quick release, and it remains extremely functional over an insect's lifetime.

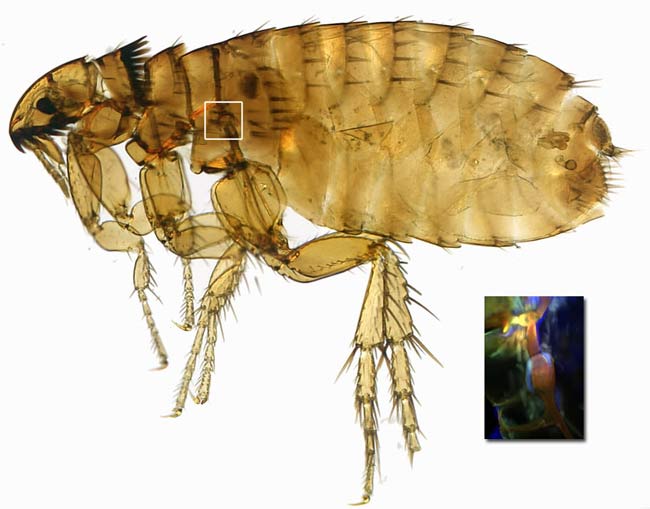

Flies take advantage of the material's durability to flap their wings more than 720,000 times an hour. Froghoppers and fleas achieve a jump acceleration of more than 400 times gravity in just one millisecond thanks to the quick release of energy from a tendon full of resilin.

While most insects use it for getting around, others, such as cicadas, moths, and some crustaceans, use it like a drum to make noise. And if incorporated into an insect's outer shell, resilin provides elasticity to an otherwise stiff structure. This is how termite queens manage to haul around a load of eggs and how ticks store their sperm.

Scientists at the Commonwealth Science and Industrial Research Organization in Australia took a copy of the resilin gene from a commonly used research fly, Drosophila melanogaster, and inserted it into the genome of E. coli bacteria. E. coli is the bacterial equivalent of a protein factory, and once the researchers had coaxed it into producing the protein, they exposed it to light to create the rubber-like molecule.

In the science world, resilience is the measure of a material's ability to recover after deformity under applied stress. Resilin is one of the most resilient materials around – it can be stretched three times its original length without breaking – and it owes its bounce-back ability to the special way its molecules are arranged.

Since it is structurally similar to elastin, the molecule that allows blood vessels to expand and contract, scientists think they may be able to use the manufactured resilin to repair stretched out, damaged blood vessels.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

This study is detailed in the Oct 13 issue of the journal Nature.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus