Arctic Methane Claims Questioned

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

A scientific controversy erupted this week over claims that methane trapped beneath the Arctic Ocean could suddenly escape, releasing huge quantities of methane, a greenhouse gas, in coming decades, with a huge cost to the global economy.

The issue being debated is this: Could the Arctic seafloor really fart out 50 billion tons of methane in the next few decades? In a commentary published in the journal Nature on Wednesday (July 24), researchers predicted that the rapid shrinking of Arctic sea ice would warm the Arctic Ocean, thawing permafrost beneath the East Siberian Sea and releasing methane gas trapped in the sediments. The big methane belch would come with a $60 trillion price tag, due to intensified global warming from the added methane in the atmosphere, the authors said.

But climate scientists and experts on methane hydrates, the compound that contains the methane, quickly shot down the methane-release scenario.

"The paper says that their scenario is 'likely.' I strongly disagree," said Gavin Schmidt, a climate scientist at the NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies in New York.

An unlikely scenario

One line of evidence Schmidt cites comes from ice core records, which include two warm Arctic periods that occurred 8,000 and 125,000 years ago, he said. There is strong evidence that summer sea ice was reduced during these periods, and so the methane-release mechanism (reduced sea ice causes sea floor warming and hydrate melting) could have happened then, too. But there's no methane pulse in ice cores from either warm period, Schmidt said. "It might be a small thing that we can't detect, but if it was large enough to have a big climate impact, we would see it," Schmidt told LiveScience.

David Archer, a climate scientist at the University of Chicago, said no one has yet proposed a mechanism to quickly release large quantities of methane gas from seafloor sediments into the atmosphere. "It has to be released within a few years to have much impact on climate, but the mechanisms for release operate on time scales of centuries and longer," Archer said in an email interview.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Methane has a lifetime of about 10 years in the atmosphere before it starts breaking down into other compounds. [What are Greenhouse Gases?]

Defending new model

Today (July 26), Peter Wadhams, a co-author of the Nature commentary, defended the work against critics in an essay posted online.

"The mechanism which is causing the observed mass of rising methane plumes in the East Siberian Sea is itself unprecedented, and the scientists who dismissed the idea of extensive methane release in earlier research were simply not aware of the new mechanism that is causing it," wrote Wadhams, an oceanographer at the University of Cambridge in the United Kingdom.

"But once the ice disappears, as it has done, the temperature of the water can rise significantly, and the heat content reaching the seabed can melt the frozen sediments at a rate that was never before possible," Wadhams added. "David Archer's 2010 comment that 'so far no one has seen or proposed a mechanism to make that (a catastrophic methane release) happen' was not informed by the ... mechanism described above. Carolyn Ruppel's review of 2011 equally does not reflect awareness of this new mechanism," Wadhams wrote.

But Ruppel, a methane hydrate expert at the U.S. Geological Survey who authored a review of research on gas hydrates in 2011, also called the sudden-thawing scenario unrealistic.

"I would say it's nearly impossible," Ruppel, chief of the USGS Gas Hydrates Project in Woods Holes, Mass., told LiveScience.

Methane: microbial or hydrate?

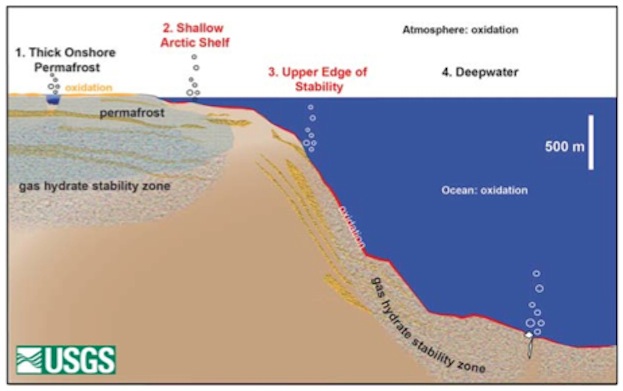

Much of the Arctic's methane sits in permafrost buried under hundreds of meters of seafloor sediments, Ruppel said. The deposits formed on exposed ground during the last Ice Age, when sea levels were lower. The rising seas have been warming the deposits for millennia. Any added warming will have to work down through the thick sediment cap.

Much of the modeling predictions in the Nature commentary were based on recent discoveries of rising methane plumes in the East Siberian Sea. However, those plumes may be from methane hydrates or from microbes.

"Methane release in the Arctic from both marine and terrestrial sources is expected to increase with warming climate, as documented in numerous papers," Ruppel said. "Much of the methane may actually be produced in the shallow sediments by microbial processes and be completely unrelated to methane hydrates."

However, there has yet to be a detectable change in Arctic methane emissions in the atmosphere over the past two decades, Ed Dlugokencky, a research scientist with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's Earth System Research Laboratory, said in an email interview.

Email Becky Oskin or follow her @beckyoskin. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.com.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus