The 'New Arctic': Thinning Ice Is Changing Ecosystem

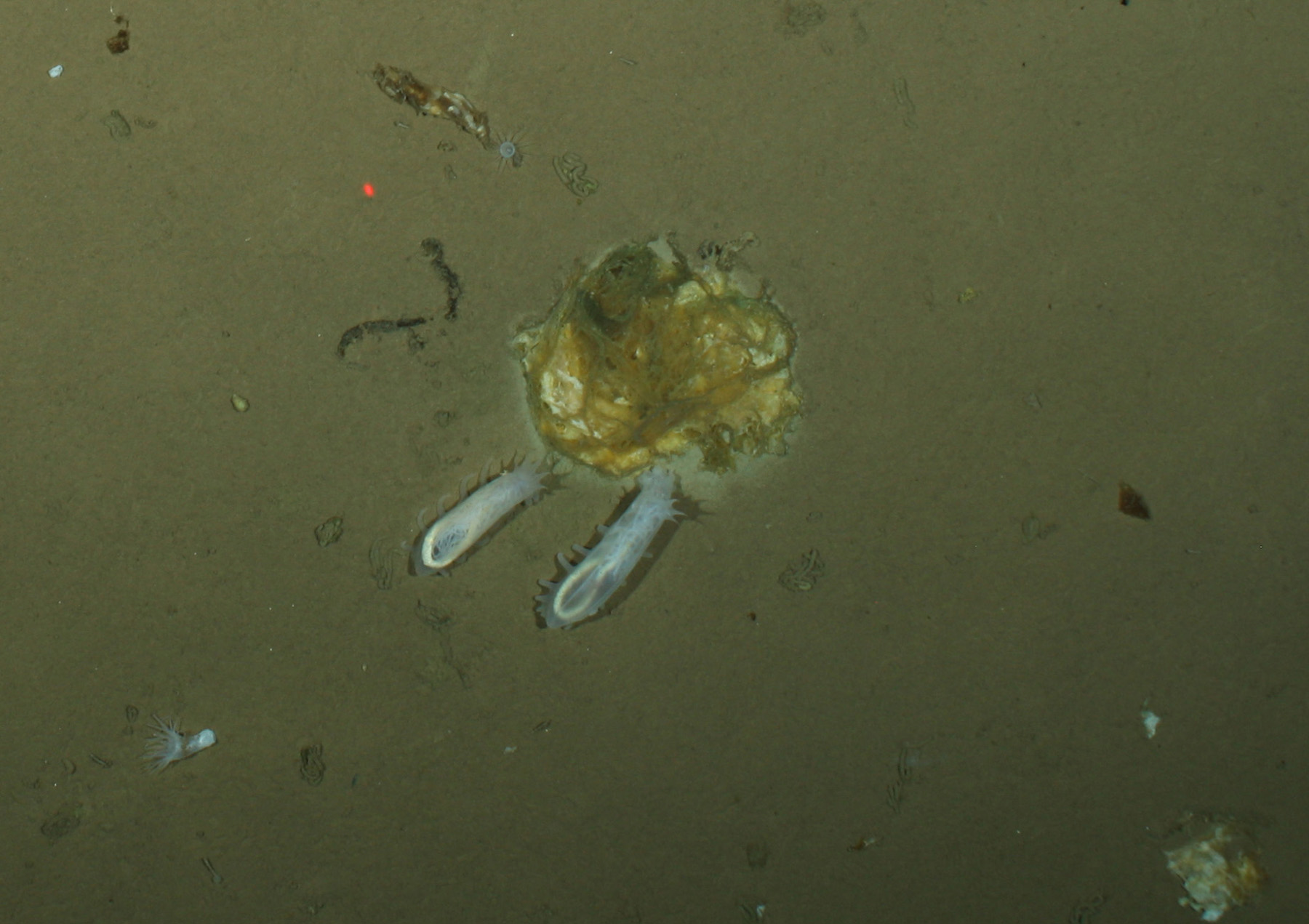

In the Arctic Ocean, algae is manna from heaven. Clumps of the aquatic life drop from the sea ice to the ocean floor below, occasionally feeding otherworldly creatures that live there, like sea cucumbers and brittle stars.

During 2012's record ice melt in the Arctic, when the ice cover over the ocean shrank to the lowest levels ever seen, researchers explored the region's seas with remotely operated vehicles. They discovered the thinning ice was speeding up algal growth.

Not only was more algae clinging to the underside of the thinning ice, but chunks of algae up to 20 inches (50 centimeters) in size littered the seafloor, covering 10 percent of the muddy bottom.

"We had cameras showing that, partially, the seafloor was green with ice algae deposits," Antje Boetius, a biological oceanographer at the Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology in Germany and lead author of the study, said in an email interview. [Video: Dive below the Arctic ice]

The vigorous algae growth could change the amount of carbon stored in the Arctic because the clumps trap carbon after falling to the seafloor. The additional food for sea creatures this algae provides could also shift the Arctic's biodiversity in unknown ways, the researchers said.

"The Arctic deep sea is normally very nutrient-limited," Boetius told OurAmazingPlanet. "We believe that we have observed a new phenomenon, which is connected to the sea ice decline, and which may change the way the Arctic ecosystem functions."

Trolling the floor

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The scientists sailed through the thinning ice in late summer 2012 aboard the research icebreaker RV Polarstern. They towed cameras and sensors along the seafloor, sent remotely operated vehicles beneath the ice, and collected water, ice and sediments for additional studies.

Clinging to the ice like vines, the 3-foot-long (1 meter) algae strands share a similarity in color and shape with "Star Wars" character Chewbacca's dreadlocks. While many kinds of algae grow under the Arctic ice, the clumps of Melosira arctica are particularly heavy compared to its brethren, and so fall to the seafloor instead of wafting in the waves to be consumed by near-surface dwellers.

The rapid growth of algae beneath the ice in 2012, quickly followed by a massive deluge of sea scum onto the ocean floor, has never been seen before, Boetius said.

"It was already known that ice algae could grow in the ice and form gigantic accumulations under the ice. But it was believed that this takes very long and that these biomasses will remain in the ice or sink out only at the warming coasts, not in the middle of the basins," she said.

The researchers think the algae clumps grew better and faster in 2012 because the Arctic's thinning ice made more sunlight available underneath the ice floes.

Signs of recent change

Once it arrives at the seafloor, up to 14,700 feet (4,500 m) below the ocean's surface, the algae gets chewed up by bottom feeders, and bacteria feed on what's left.

By calculating how much carbon and nutrients were cycled by the algae and its predators, the research team confirmed the rapid growth in 2012 was a new phenomenon.

"We have seen how this was re-mineralized by seafloor bacteria. Had this occurred many times before, the seafloor would look very different," Boetius said.

The expedition's zoologist also analyzed the stomach contents of sea cucumbers from the deep Arctic sea: Algae extracted from their guts could still photosynthesize upon returning to the ship's laboratory, evidence that the algae clumps were relatively young. The animals also had highly developed gonads, another sign of recent access to a massive food supply.

"I think we have probably seen a glimpse of the new Arctic," Boetius said.

Reach Becky Oskin at boskin@techmedianetwork.com. Follow her on Twitter @beckyoskin. Follow OurAmazingPlanet on Twitter @OAPlanet. We're also on Facebook and Google+.