Coldhearted Psychopaths Feel Empathy Too

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Psychopaths may be capable of empathizing with others in some situations, a new study has found.

The study's researchers investigated the brain activity of psychopathic criminals in the Netherlands. As expected, the psychopaths' brains showed less empathy than mentally healthy individuals while watching others experience pain or affection. But when asked to empathize, the psychopaths appeared to show normal levels of empathy, suggesting the ability to understand another's feelings and thoughts may be repressed in these individuals rather than missing entirely.

Psychopaths are traditionally characterized as manipulative individuals who lack the capacity for empathy. Their unnerving detachment seems to make it easier for them to harm others. [The 10 Most Controversial Psychiatric Disorders]

"Psychopaths can be sometimes very charming and socially cunning, and other times be callous and perform atrocities," said study researcher Christian Keysers, a neuroscientist at the University of Groningen in the Netherlands.

When healthy people see others perform an action, that observation turns on "action" areas of their own brain — known as the mirror neuron system. Similarly, when people experience pain or pleasure, they mimic these feelings in their own brains, too, Keysers told LiveScience.

Few studies have looked at what's going on in the brains of psychopaths in situations that elicit empathy in normal people.

Empathetic brains

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Keysers and his colleagues obtained rare access to a group of psychopathic criminals for the study.

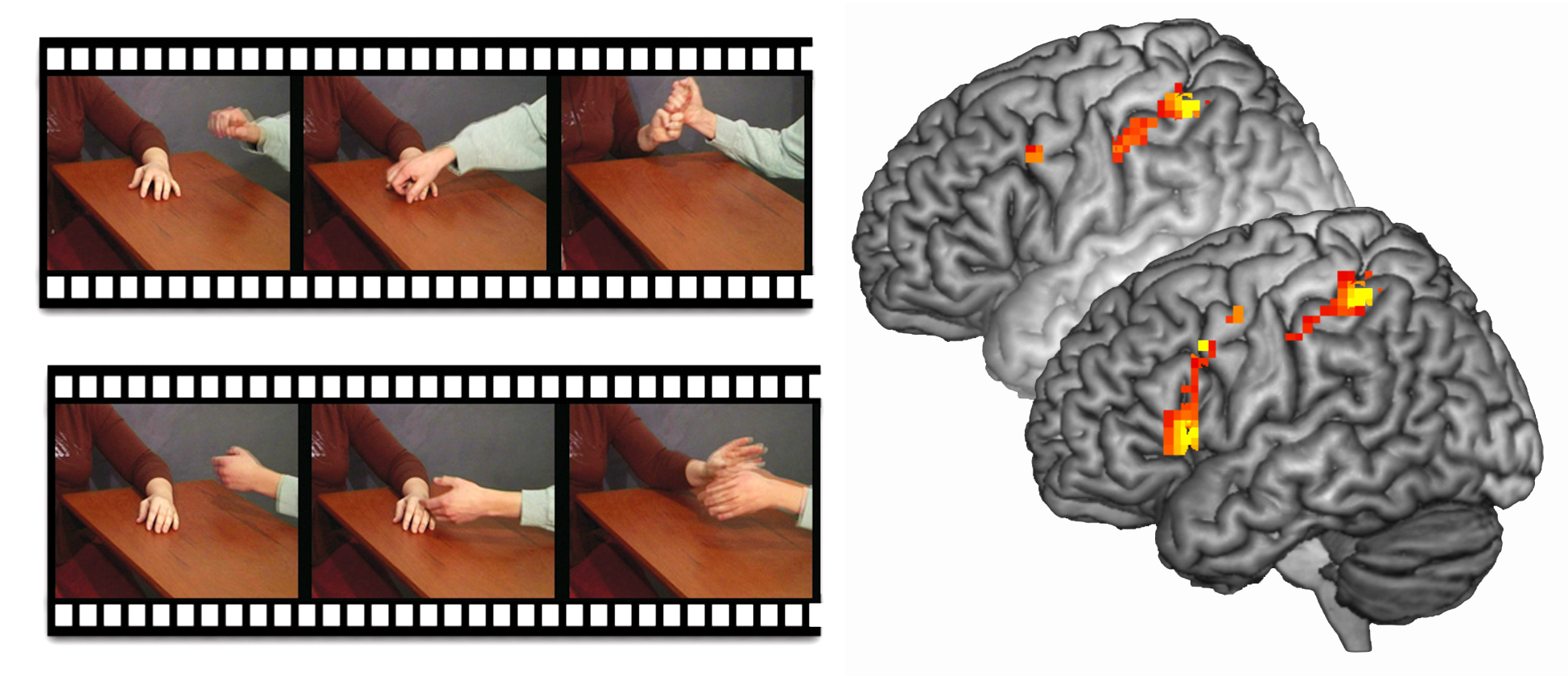

The psychopaths were put in a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scanner and shown movies depicting two hands interacting in a loving or a painful way, such as one hand stroking or hitting the other.

First, they simply watched the movies in the scanner. Then the researchers instructed the participants to watch the movies again and attempt to empathize with the subjects in the movies. (Specifically, they were told to "feel with the receiving or the approaching hand.") The researchers also performed the same hand actions on the psychopaths' own hands, to see whether it activated the same brain areas as watching the movies did. They compared the brain activity of the psychopaths with that of healthy people viewing the movies.

The scientists looked at brain activation in three areas associated with a person's own actions or feelings: the premotor system, which plans movements; the somatosensory system, which is responsible for feelings of pain; and the insula, which lets people feel emotional pain. When the psychopaths watched the movies the first time, their brains showed decreased activity in these areas compared with healthy individuals. This finding supports the notion that psychopaths feel less empathy toward others.

But surprisingly, when the psychopaths were instructed to try to empathize while watching the videos, their brains showed the same level of activity in these brain areas as normal individuals.

"They seem to have a switch they can turn on and off that turns their empathy on and off depending on the situation," Keysers told LiveScience.

Treating psychopaths

The findings suggest psychopaths are, in fact, capable of empathy, if they consciously control it. This ability may explain why a psychopath can be charming in one instant, and brutal the next, the researchers say.

The idea also has implications for therapy. Most current therapies assume psychopaths lack empathy, and so try to produce the ability. Rather than creating empathy in psychopaths, therapists could find ways to make it automatic, Keysers said.

Mbemba Jabbi, a neuroscientist at the NIH's National Institute of Mental Health, who was not involved with the study, found the results convincing. When it comes to empathy, "psychopaths maybe have a different baseline," Jabbi said, just as "somebody with a thick skin gets the sensation of a pinch much more slowly." He added that future studies should investigate more sophisticated, emotional forms of empathy.

The findings were detailed today (July 24) in the journal Brain.

Follow Tanya Lewis on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.com.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus