Weird Quantum Entanglement Achieves New Record

A new breakthrough in the strange business of "quantum entanglement" may make measuring eerily connected particles easier than ever, scientists say.

Under the mind-bending rules of quantum mechanics, two particles can become entangled so that they retain a connection even when separated over long distances. The properties between the two are correlated so that an action performed on one will affect the other.

To study entangled particles, physicists have to be able to detect them. In some experiments, researchers measure one of the entangled pair first, and its presence signals, or "heralds," the presence of the second particle. Recently, a team of physicists at the Joint Quantum Institute in College Park, Md., achieved a new record in heralding efficiency, meaning they were able to detect twin particle pairs more efficiently than ever before. [How Quantum Entanglement Works (Infographic)]

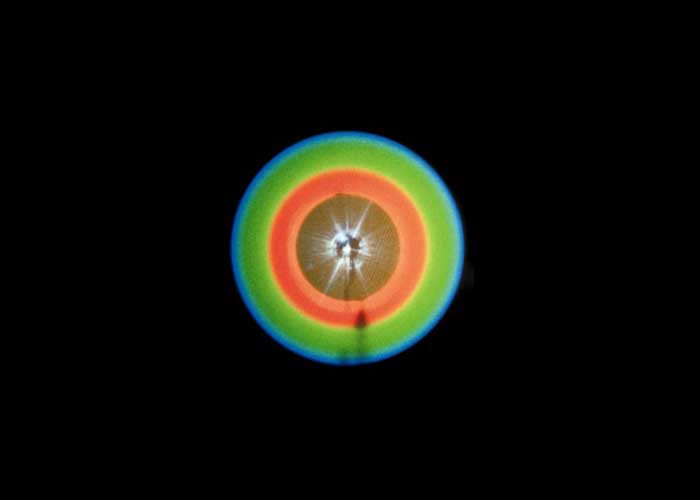

In the experiment, the researchers used what's called a pump laser to produce a beam of light that passes through a special type of crystal. Occasionally, the photons of light in the laser beam will split in two, essentially, while passing through the crystal, creating a new pair of correlated photons. These photons will hit a detector screen in a precise spot, so if the researchers find one, they know where to look to find the other.

Making these types of measurements requires extreme precision and exact alignment. "That alignment is difficult, because when I'm off, I still see plenty of light, it's just not the right light," said Joint Quantum Institute physicist Alan Migdall, who led the study.

To tell whether these photon pairs are entangled, the researchers look for particles arriving at the detectors at the same time.

"We have photon counters," Migdall explained. "An incoming photon goes 'click,' then we look on the other side, and if the photons are just random, the time between one detector clicking and the other could be any time difference. But if they're born at the same time, then there's a high likelihood that the other detector clicks within, say, a nanosecond."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Improving the efficiency of these heralding measurements will aid in attempts to understand the nature of quantum entanglement, the scientists said. For example, the photon pair creation mechanism used in Migdall's lab can be applied to what's called a Bell test, which is used to determine whether two particles are truly entangled.

"The idea is that we're creating a pair such that they have a determined joint property, but the individual property is not just unknown, but doesn't even exist," Migdall told LiveScience. That's because in the weird world of quantum physics, a particle's properties remain undetermined, existing in a sea of probability, until pinned down by an actual measurement. When a measurement is performed on one entangled particle, its own properties, as well as those of its twin, come into existence.

Performing tests on entangled particles is akin to interviewing separate suspects who might have cooperated on a shared crime, Migdall said.

"You pick up two suspects for a crime, and they typically separate them and ask questions where they can't hear each other," he said. "Then they compare to see if the stories come out straight. It's a little bit like that."

If the suspects' stories match, they're likely telling the truth. If the particles' properties match, they're entangled.

The research was published in the May 15 issue of the journal Optics Letters.

Follow Clara Moskowitz on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.com.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus