Why does copper turn green?

Like some other metals, it oxidizes when left out in the elements, but the coloring process is complicated.

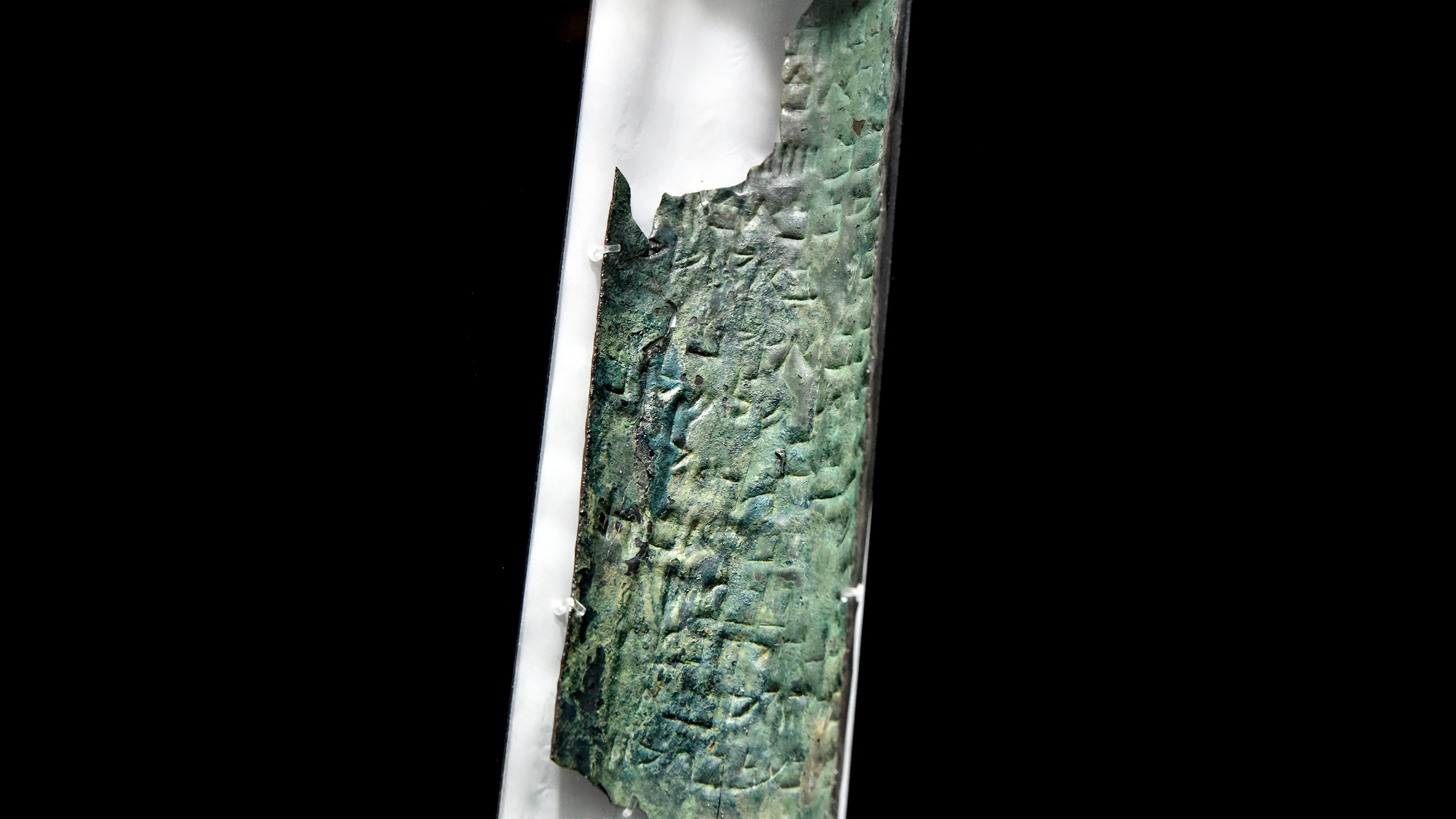

Copper has a beautiful reddish hue, but when exposed to the elements, the metal undergoes a series of chemical reactions that make it turn green.

But why does this color transformation occur? The answer, it turns out, is similar to why iron rusts; if iron is left unprotected in open air, it will corrode and form a flaky orange-red outer layer.

"When copper metal corrodes, it forms what is called an oxide layer," Paul Frail, an advanced senior engineer in corrosion treatments with Suez Water Technologies & Solutions based in Trevose, Pennsylvania, told Live Science.

The oxide layer, Frail explained, forms when the surface of copper reacts with the oxygen and water present in Earth's atmosphere. The layer is made up of copper salts and oxygen, and becomes thicker over time. Eventually, the copper underneath the layer is no longer exposed enough to the air to react.

Related: Why do some fruits and vegetables conduct electricity?

"Initially, the film may looked tarnished or black," said Frail, who is also a member of the American Chemical Society. "As the oxide film matures and grows more color, it will begin to [change], ranging from yellow-reds, blues and to a greenish color."

The Statue of Liberty, he noted, is a famous example of copper turning green, as is copper metal used in other types of statues, and in older buildings for government, offices and universities.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The color we see on older copper exposed to the air is not directly due to copper oxide, or the reaction of copper with oxygen in dry air, said Mark Jones, a retired chemist with Dow Chemical.

When the oxide reaction occurs, the oxides are not colored. Rather, the color comes from "reactions of traces of sulfate and chloride in the atmosphere with the copper oxide," Jones told Live Science. Sulfur oxides come from combustion of fuels with sulfur, for example, and then fall on to the copper through rain.

"They react with the oxides on the surface [of the copper] and give color," Jones said of the sulfur oxides, which are always present at low levels in the air. This is one demonstration of how copper's gradual color change requires multiple steps.

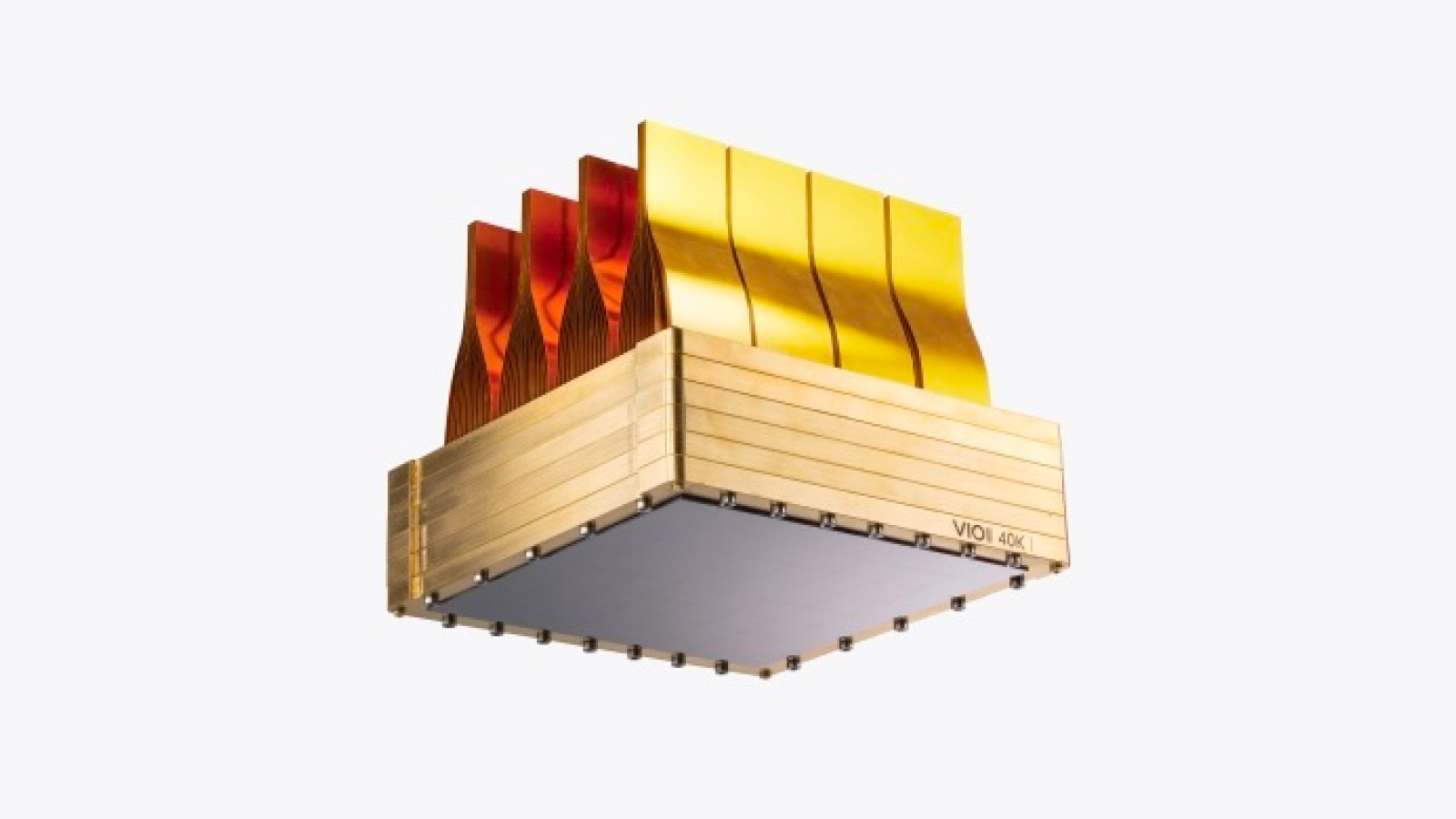

On the periodic table of elements, copper is situated next to nickel and zinc in the first row of what is called transition metals, which refer to metallic metals with certain properties.

These properties include being good conductors of electricity, being resistant to corrosion, being very malleable (or shapable) and serving as good transfers of heat.

Copper, like these other metals, can easily be combined to form alloys, Frail noted, which have popular properties in construction including slow corrosion when compared with iron. "A common alloy of copper is brass, where copper is mixed with zinc," Frail said.

Copper also sits above silver and gold on the periodic table, meaning it has similar chemistry to these elements, Jones said. None are rapidly oxidized, he noted; while gold is completely resistant to oxidization, silver is less resistant than gold and copper even less so than gold or silver.

"All these traits, and its higher natural abundance than gold and silver, contribute to copper's use in electrical applications," he added. Copper is also the major component of the catalyst used to make methanol and vinyl chloride.

Originally published on Live Science on Feb 9, 2013 and rewritten on June 28, 2022.

Elizabeth Howell was staff reporter at Space.com between 2022 and 2024 and a regular contributor to Live Science and Space.com between 2012 and 2022. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, speaking several times with the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.