Mug Shots: 10 Lost Amphibians

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Lost Amphibians

Scientists are on the look-out for "lost amphibians" animals considered possibly extinct but that may be holding on in a few remote places. There may be up to 100 of them hiding in the world's forests.

Here are just a few of the many fascinating amphibian species who have not been seen for over a decade. Some may be lost forever, while others may still exist, hidden under rocks in a remote stream, waiting to be rediscovered.

Golden toad (Incilius periglenes), Costa Rica

The Golden toad was last seen in 1989 and is perhaps the most famous of the lost amphibians. The species went from abundant to extinct in a little over a year in the late 1980s.

Golden toads were originally discovered in 1966 in western Costa Rica's Monteverde Cloud Forest, where populations of other amphibian species have also collapsed, a development thought to be linked to climate change and disease.

Gastric brooding frog (Rheobatrachus silus), Australia

Gastric brooding frogs come in two species: Rheobatrachus vitellinus and R. silus (pictured above and last seen in 1985).

These frogs had a unique mode of reproduction: Females swallowed eggs, raised tadpoles in their stomaches and gave birth to froglets through the mouth.

The reason for the frogs' decline is unknown. Timber harvesting and the chytrid fungus are the main suspects.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Mesopotamia Beaked Toad (Rhinella rostrata), Colombia

This frog with a distinctive pyramid-shaped head was last seen in 1914.

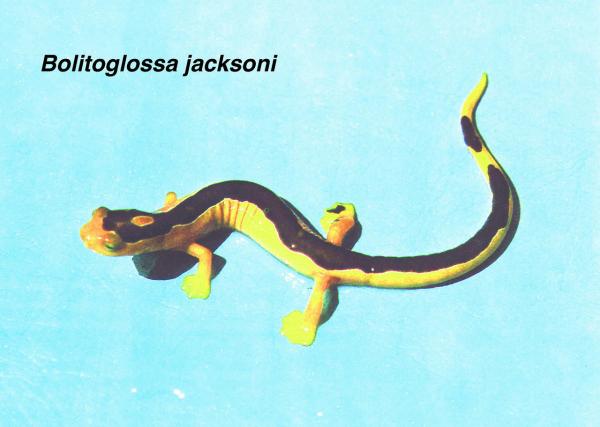

Jackson's climbing salamander (Bolitoglossa jacksoni), Guatemala

This black and yellow salamander one of only two known specimens is believed to have been stolen from a California laboratory in the mid 1970s was last seen in 1975.

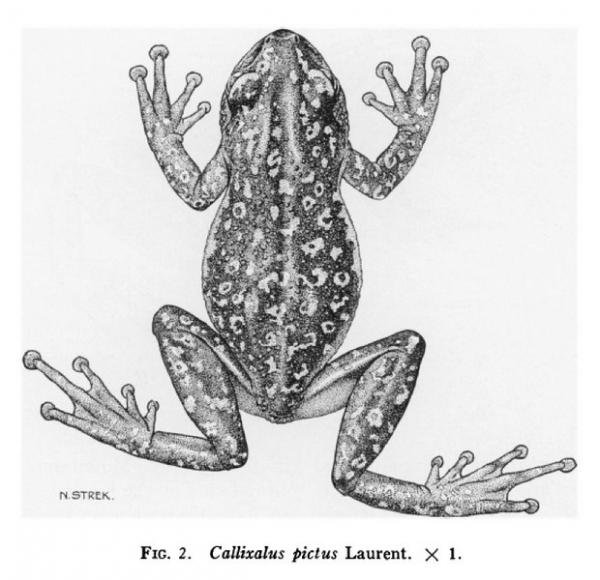

African Painted Frog (Callixalus pictus), Democratic Republic of Congo/Rwanda

Very little is known about this animal which is never thought to have been photographed. It resides in high-altitude forests, especially bamboo forest, but the frog hasn't been recorded since 1950, possibly due to a lack of field work in the area

Rio Pescado Stubfoot Toad (Atelopus balios), Ecuador

Last seen in April 1995 and may well have been wiped-out by chytridiomycosis.

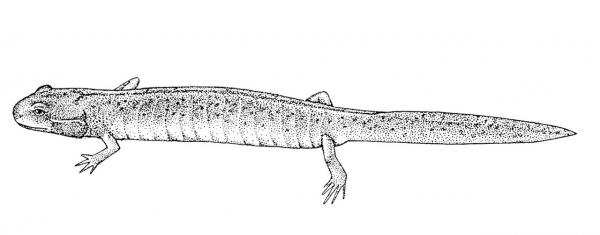

Turkestanian salamander (Hynobius turkestanicus), Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan or Uzbekistan

Last seen in 1909 and known from only two specimens collected that year. All the collected specimens have since been lost and no other records are known.

Scarlet frog (Atelopus sorianoi), Venezuela

The Scarlet frog was last seen in 1990 and is known only from a single stream in an isolated cloud forest.

Hula painted frog (Discoglossus nigriventer), Israel

The Hula painted frog was last seen in 1955 when a single adult was collected. Efforts to drain marshlands in Syria to eradicate malaria may have been responsible for the disappearance of this species.

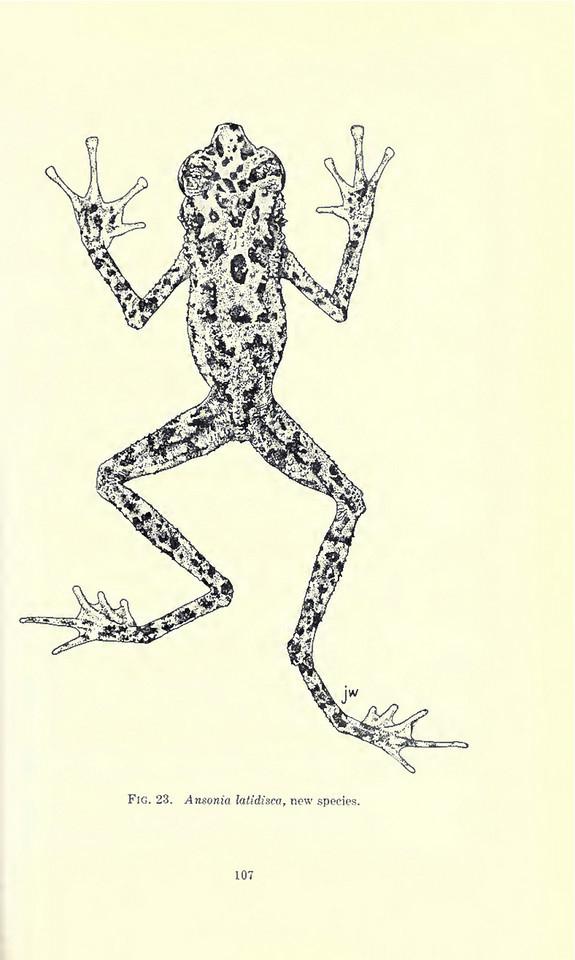

Sambas Stream Toad (Ansonia latidisca), Borneo (Indonesia and Malaysia)

Last seen in the 1950s, increased sedimentation in streams after logging may have contributed to this toad's decline.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus