Intraterrestrials: Life Thrives in Ocean Floor

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

An entire ecosystem living without light or oxygen flourishes beneath the ocean floor, a new study confirms.

Scientists call it the dark biosphere, and it's potentially one of the biggest ecosystems on the planet. Buried oceanic crust covers 60 percent of Earth's surface. For the first time, researchers have pulled up pieces of the crust and examined the life within. In its rocks, microbial communities thrive, eating altered minerals for food, the study found.

"They're gaining energy from chemical reactions from water with rock," said Mark Lever, a microbiologist at Aarhus University in Denmark and lead author of the study, published in the March 15 issue of the journal Science.

"Our evidence suggests that this is an ecosystem that is based on chemosynthesis and not on photosynthesis, which would make it the first major ecosystem on Earth that is based on chemosynthesis," Lever told OurAmazingPlanet. [Strangest Places Where Life Is Found on Earth]

While bacteria and other microbes have been noted in deep boreholes drilled into the seafloor, the discovery confirms the extent of the life within the oceanic crust, as well as the possibility of life on other planets, the study scientists said.

"I think it's quite likely there is similar life on other planets," Lever said. "On Mars, even though we don't have oxygen, we have rocks there that are iron-rich. It's feasible that similar reactions could be occurring on other planets and perhaps in the deep subsurface of these planets."

This week, NASA scientists announced the discovery of the chemical ingredients for life in Mars rocks, including sulfur, nitrogen, hydrogen, oxygen, phosphorus and carbon. The discovery suggests Mars could have once supported microbial life, scientists said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Life inside Earth

The microorganisms living in the seafloor are diverse, consuming hydrogen, carbon, phosphorus and other elements, but for this study, researchers focused on methane-producing and sulfur-reducing species. The bacteria get their sustenance from inorganic molecules created during the chemical alteration of rocks by water. After consuming their "food," the microbes emit methane or hydrogen sulfide (rotten-egg gas) as waste.

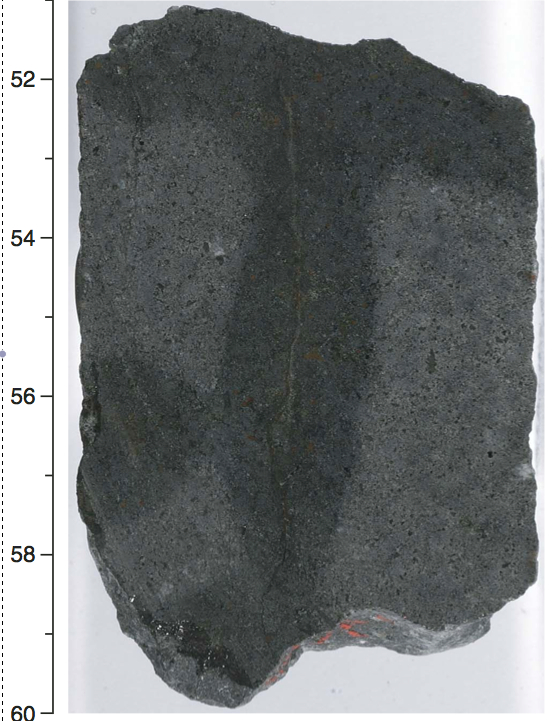

Lever nabbed the rocks and their microbes in 2004, during an international research expedition to the eastern flank of the Juan de Fuca Ridge off the Washington coast. There, the water is 8,500 feet (2.6 kilometers) deep and an 850-foot (260 meters) blanket of mud buries the crust. Detailed studies by other groups show seawater circulates through the crust here.

The Juan de Fuca Ridge is a spreading center, where hot lava wells out of the Earth and creates new basalt rock. The drilling site was 62 miles (100 km) away from the ridge, in 3.5-million-year-old basalt. It was also 34 miles (55 km) from the nearest outcrop where water enters the basalt, Lever said. The rocks from the borehole were up to 980 feet (300 m) deep.

DNA evidence indicates the organisms are modern and not 3.5-million-year-old fossils, Lever said. Under careful handling to prevent contamination, Lever also raised the bacteria in a lab at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, for five years. The microorganisms released puffs of methane, adding proof of an active crustal community.

Katrina Edwards, a microbiologist at the University of Southern California, said Lever and his colleagues "dealt superbly" with potential contamination issues related to retrieving microbial life from oceanic crust. "They did a marvelous job of addressing those concerns," said Edwards, who was not involved in the study.

Dark biosphere

"These results are incredibly important for our understanding of the deep biosphere in hard rock environments," Edwards added. "The oceanic crust is the most ubiquitous ecosystem on our planet. Most of the microbial ecosystems on our planet exist in the dark. We're so biased to light because that's where we live, but in fact, most of the biosphere exists in the dark," she told OurAmazingPlanet.

Researchers like Lever and Edwards are not only interested in the scope of intraterrestrial life — the biosphere living in the Earth's crust — but they hope to determine how the deep bacteria changes the global carbon cycle and oceans.

As the microbes leach out minerals and excrete waste, they alter the chemical composition of rocks and circulating seawater. This underground factory could substantially alter the composition of the world's oceans, though no one yet knows to what extent.

"There could potentially be a substantial biomass of organisms converting carbon dioxide into biomass and acting as a carbon sink," Lever said. "We also know roughly 4 percent of Earth's ocean volume is circulating through the crust, so there are many implications for how microorganisms that are present in the crust may influence global elemental cycles," he said.

However, not all of the ocean's crust may have the right conditions to support such an active ecosystem. Some regions may not have circulating water, or could run out of oxidized minerals, leaving no energy available for life. Also, some parts of the crust have oxygen-based life, Lever said.

"I think it's likely that there's life everywhere to the same extent, but we don't know," Lever said.

But Lever said finding microorganisms in basalt was not a surprise. Basaltic crust was likely the first hospitable site on Earth for live, and the methane-producing bacteria are thought to be the first life to evolve on the planet, he said. Close cousins to the bacteria found in the study's rock samples now live in rice field soil and sewage sludge. [7 Theories on the Origin of Life]

"These are ancient organisms," Lever said. "They've been around for a very long time and spread all over the world."

Email Becky Oskin or follow her @beckyoskin. Follow us @OAPlanet, Facebook or Google+. Original article on LiveScience's OurAmazingPlanet.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus