51 Facts About Sex

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Steamy Sex

That three-letter word that can make you both blush and say "aahhh" is more than a simple act of lust. Sex has been around since, oh yeah, nearly the beginning of time. And since then scientists and enthusiasts alike have delved into understanding and even improving the act and its outcomes. Here's a look at some of the coolest facts about S-E-X.

The Basics

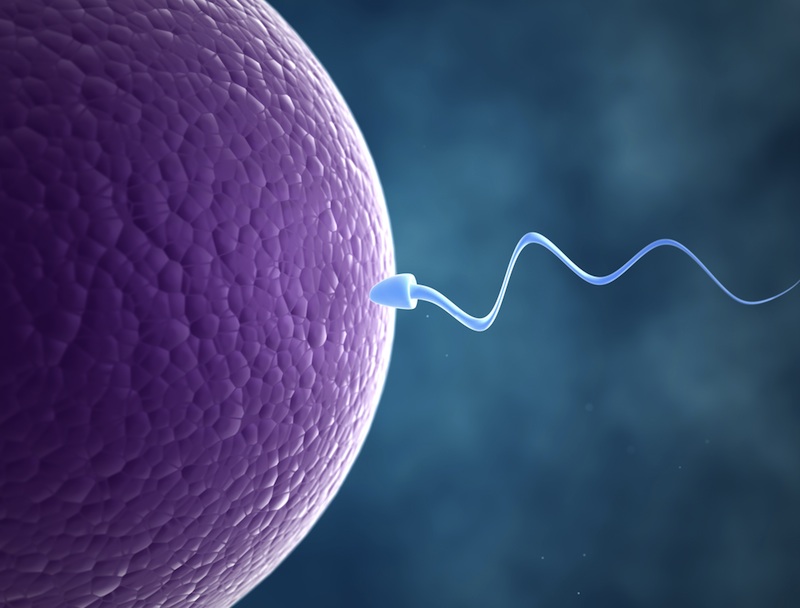

Let's get down to business about the facts of life: Sex is made for mixing and mingling genes. These genes are carried by the male and female gamete cells, the sperm and eggs. Most of the time, a woman releases one egg per month, but men are much more prolific. In a single ejaculation, a guy sends between 30 million and 750 million sperm swimming toward that egg.

Piggie sperm

Human males have nothing on pigs, though. A single swine ejaculate contains about 8 billion sperm cells.

Sex on the brain

Humans start to think about sex relatively early in our life spans. By age 19, about 70 percent of American teenagers have had sex.

Sperm survival

Unintended pregnancies are all too common, but the stars do have to align to get a single sperm to a ready egg. Women are fertile for about three to six days each month, depending on their menstrual cycle. Sperm can hang around in the reproductive tract for up to five days and survive, but it's rare for them to remain viable for more than two days or so.

Fertility god

Trying to keep these stars from aligning may be tough, though. With typical use, fertility-awareness methods of birth control (when a couple avoids sex during fertile days) result in 24 pregnancies for every 100 couples who use these methods each year.

Body heat

Ovulation heats up a woman's body by as much as half a degree Fahrenheit. Before ovulation, most women run between 96 and 98 degrees F (35.5 to 36.6 degrees Celsius). Right after ovulation, body temperature goes up to around 97 to 99 degrees F (36.1 to 37.2 degrees C). The most effective fertility-awareness methods of birth control require daily temperature-taking to detect ovulation.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Bestiality is risky

Bestiality is generally frowned upon. Here's one more reason to abstain: A 2011 study found that sex with animals, such as chickens, pigs and horses, is linked to penile cancer, perhaps because microtrauma to the penis during these acts lets foreign microorganisms in. Some microorganisms, such as the human papilloma virus (HPV), can cause cancer in humans.

Boob buttons

It's no accident that nipples are erogenous zones. Brain-imaging research on women has shown that sensory signals from the nipples end up in the same area of the brain that stimulation from the vagina, cervix and clitoris do. []

Oh how exciting!

Humans sometimes go to strange lengths for sex. Take the alleged aphrodisiac Spanish fly. It's a ground-up bug called a blister beetle that contains the acid cantharidin. When taken and excreted, it causes a burning sensation in the urethra that apparently passes for sexual excitement in some circles. Oh, and the powder is toxic. [Top 10 Aphrodisiacs]

Sex 101

Learning about sex makes you more likely to go out and do it, right? Nope. According research published in 2012 by the nonprofit Guttmacher Institute, any sex education at all delays teen sex.

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus