Scientists Chuck Instruments Off Planes Into Cracks in Arctic Sea Ice

As sea ice disappears in the Arctic Ocean, the U.S. Coast Guard is teaming with scientists to explore this new frontier by deploying scientific equipment through cracks in the ice from airplanes hundreds of feet in the air.

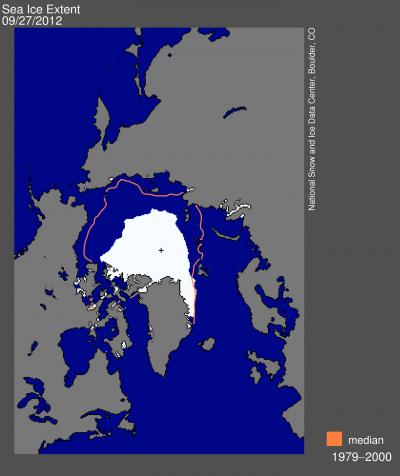

This year, the amount of sea ice that normally covers giant swaths of the Arctic Ocean fell to a record low level; this summer, the Arctic ice cap meltedto 1.32 million square miles (3.41 million square kilometers), its lowest extentsince measurements began in the late 1970s, according to the U.S. National Snow & Ice Data Center, which tracks sea ice using satellite data.

"It used to be that the ice just pulled back a bit from the beach each year," said oceanographer Jamie Morison of the University of Washington. "Now we're seeing huge areas of open water."

Northern sea ice has been retreating and thinning over the past few decades due to the increased warming in the Arctic, a consequence of the buildup of greenhouse gases in Earth's atmosphere that trap heat from the sun. This long-term decline could have dramatic effects on Arctic wildlife and open up international territorial squabbles over the fabled Northwest Passagethat serves as a shortcut between Europe, Asia and the Americas.

"The changes in sea ice are more substantial than many of us would have expected and than are currently predicted," researcher Axel Schweiger, a climatologist at the University of Washington, told OurAmazingPlanet. [Infographic: Arctic Sea Ice Hits a Record Minimum]

"While certainly worrisome, these dramatic changes also offer an exciting opportunity to better understand the environment," Schweiger added. Scientists hope to better understand a bevy of questions about the polar environment: Will storms be enhanced by warmer, more expansive open water? Will we see an increase in winds that will keep the ice open or cool the ocean more quickly?

Enter the Coast Guard.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Tracking the ice

Faced with a vast expansion of the amount of water over which it must monitor ship traffic and perform search-and-rescue operations, the Coast Guard has begun making regular flights over the Arctic using versatile C-130 Hercules transport planes taking off from Kodiak, Alaska. They offered researchers the chance to tag along with these flights to take repeated ocean, ice and atmospheric measurements in the Arctic.

"The exciting thing is that this collaboration allows us to start tracking changes in the seasonal ice zone before the seasonal melt back begins and follow it through to the fall. That's never been done before," Morison told OurAmazingPlanet. [10 Things to Know About Sea Ice]

The scientists want to see what effects the lack of ice cover might have on the Arctic. For example, without ice reflecting sunlight back at space, ocean surface temperatures can be 9 to 11 degrees Fahrenheit (5 to 6 degrees Celsius) warmer than previously. This rise in ocean temperature can in turn affect the flow of water in the oceans, potentially influencing how fast or slow ice melts or grows, as well as circulation patterns in the atmosphere, which interacts with the ocean.

The researchers have modified scientific equipment so they can toss it out of fast-flying airplanes rather than deploying it by slower-moving ships. For instance, one buoy used by the International Arctic Buoy Program can get rolled out the back of an airplane flying about 300 feet (100 meters) above the surface, with a parachute to slow its fall. This device holds instruments that transmit air temperature and pressure data to scientists via satellite.

The Coast Guard benefits from this data as well, as the buoys provide information about air pressure and temperature. "This weather data helps them fly safely," said mathematician Ignatius Rigor at the University of Washington, who coordinates the International Arctic Buoy Program.

Repeat measurements

Coast Guard crews have also deployed tube-shaped packages 3 feet (1 m) long out the side doors of planes. Once in the water, the package drops a torpedo-shaped sensor probe that sinks to a depth of about 3,300 feet (1,000 m) in about 10 minutes. This probe is connected via a thin copper wire to a radio transmitter that floats on the surface. The probe relays data about deep-sea water temperature and saltiness.

"Ocean instruments have been deployed from aircraft for a long time. We have also done ocean studies using instruments thrown from aircraft into cracks of sea ice at a smaller scale," Schweiger said. "What is new about this program is the ability to get a lot of repeat measurements for the same area and combine both ocean and atmospheric measurements."

The flights have taken place monthly since the summer, with the Coast Guard deploying 19 probes as far as 80 degrees north latitude, far past most land masses. The final flight this year will be in mid-October, after which it gets dark too quickly to fly very far. The researchers hope to continue their collaboration with the Coast Guard in years to come.

"We need to continue these measurements for a few seasons to sift real trends from interannual variability," Morison said.

This story was provided by OurAmazingPlanet, a sister site to LiveScience.