'Jurassic Park' May Be Impossible, But Dino DNA Lasts Longer Than Thought

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

In "Jurassic Park," scientists extract 80-million-year-old dino DNA from the bellies of mosquitoes trapped in amber. Researchers may never be able to extract genetic material that old and bring a T. rex back to life, but a new study suggests DNA can survive in fossils longer than previously believed.

The oldest DNA samples ever recovered are from insects and plants in ice cores in Greenland up to 800,000 years old. But researchers had not been able to determine the oldest possible DNA they could get from the fossil record because DNA's rate of decay had remained a mystery.

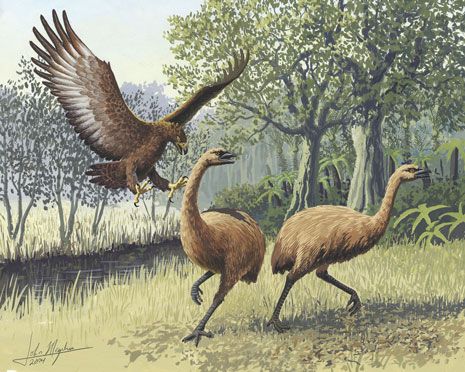

Now scientists in Australia report they've been able to estimate this rate based on a comparison of DNA from 158 fossilized leg bones from three species of the moa, an extinct group of flightless birds that once lived in New Zealand. The bones date between 600 and 8,000 years old and importantly all come from the same region.

Temperatures, oxygenation and other environmental factors make it difficult to detect a basic rate of degradation, researcher Mike Bunce, from Murdoch University's Ancient DNA lab in Perth, explained in a statement.

"The moa bones however have allowed us to study the comparative DNA degradation because they come from different ages from a region where they have all experienced the same environmental conditions," Bunce said.

Based on this study, Bunce and his team put DNA's half-life at 521 years, meaning half of the DNA bonds would be broken down 521 years after death, and half of the remaining bonds would be decayed another 521 years after that, and so on. This rate is 400 times slower than simulation experiments predicted, the researchers said, and it would mean that under ideal conditions, all the DNA bonds would be completely destroyed in bone after about 6.8 million years.

"If the decay rate is accurate then we predict that DNA fragments of sufficient length will preserve in frozen fossil bone of around one million years in age," Bunce said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But he cautioned that more research is needed to examine the other variables in the breakdown of DNA.

"Other factors that impact on DNA preservation include storage time following excavation, soil chemistry and even the time of year when the animal died," Bunce said in a statement. "We hope to refine predictions of DNA survival by more accurately mapping how DNA fragments decay across the globe."

The study was published Oct. 10 in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

Follow LiveScience on Twitter @livescience. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus