Wipe out: History's 7 most mysterious extinctions

Mysterious Wipe-Outs

What do the dinosaurs, the dodo bird and the Tasmanian tiger all have in common? They're all extinct. Countless species have come and gone in the history of our planet, some leaving more of a mark than others. Sometimes the cause of a species' extinction is unknown. To understand and explain these deaths, scientists often work with numerous hypotheses and constantly hunt for more data to unravel the mysteries.

From the fearsome megalodon to the awkward elephant bird, here are some of history's most puzzling extinctions.

Rocky Mountain Locust

When thinking about extinctions, dinosaurs, dodos and other large creatures typically come to mind. But insects can also disappear — and in a relatively short amount of time, too. Between 1873 and 1877, huge swarms of the Rocky Mountain locust (Melanoplus spretus) reportedly caused hundreds of millions of dollars in damage as they ravaged crops throughout the Midwestern United States. Less than 30 years later they were extinct.

So what happened? Many theories point to large-scale environmental changes, such as the disappearance of the buffalo and their locust-breeding wallow habitats. But evidence suggests that innumerable locust eggs may have succumbed to plowing and irrigation used by the very farmers the insects terrorized. Some scientists think that the lack of genetic variation may have added to the locusts' troubles.

Megalodon

Between 28 million and 1.5 million years ago, megalodon ruled Earth's oceans. This terrifyingly large shark, which dined on giant whales with its 7-inch-long (18 cm) teeth, reached a maximum length of over 60 feet and weighed as much as 100 tons. For comparison, great white sharks — megalodon's closest living relative — rarely reach the 20-foot (6 m) mark.

So what could cause a monster at the top of the food chain to sputter out of existence? Theories abound. One idea posits that megalodon couldn't handle the oceanic cooling and sea level drops that came with the ice ages of the late Pliocene and early Pleistocene epochs. On the other hand, another explanation ties the shark's demise to the disappearance of the giant whales it fed on.

Woolly Mammoth

For 250,000 years, the woolly mammoth (Mammuthus primigenius) enjoyed an expansive range that covered parts of North America, Europe and Asia. A small population survived on Wrangel Island in the Arctic Ocean until 3700 years ago, while the rest of the hairy giants disappeared from their Siberian habitat some 10,000 years ago.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

A long-standing theory proposes that early humans hunted the woolly mammoth to extinction. On the other hand, some scientists believe a global shift toward freezing temperatures did the beasts in. But perhaps no single culprit should be blamed. A study detailed online June 12, 2012, in the journal Nature Communications claims that a combination of factorscontributed to the mammoth's downfall.

Broad-Faced Potoroo

After Europeans settled Australia a few hundred years ago, the country suffered many species' extinctions. Some creatures declined due to land-clearing practices; others suffered because of the predatory red fox, which was initially introduced to Australia in the mid-1800s for hunting purposes. However, the broad-faced potoroo (Potorous platyops) appears to have taken a severe hit before the settlers arrived — an unusual occurrence among recently extinct Australian species.

Researchers collected the last few specimens of the broad-faced potoroo — a marsupial less than 10 inches long around 1875. It's unknown how long the animals survived after that. It's also not clear what finally pushed the marsupials over the edge, but studies suggest predation by feral cats, which likely made it to the continent by way of Dutch shipwrecks in the 17 century, played a large role. [Marsupial Gallery: A Pouchful of Cute]

Atelopus longirostris

Atelopus longirostriswas a toad native to the humid forests of northern Ecuador. A. longirostris — named so for it's long snout — has not been recorded since 1989.

The cause of the amphibian's extinction has not been determined, but scientists think chytridiomycosiswas certainly involved. In recent years, the disease chytridiomycosis, which is caused by the fungus Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis, has become world famous as a frog killer, boasting a 100 percent mortality rate for some amphibian species. Researchers think A. longirostris may have had to contend with climate change and habitat loss, in addition to the deadly disease.

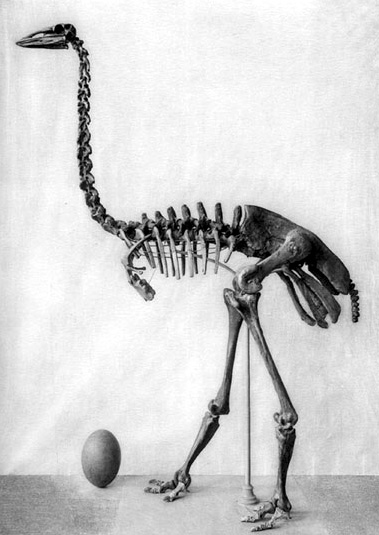

Elephant Bird

The dodo may be the poster child for species extinction, but it's not the only flightless bird to bite the dust. Enter the elephant bird. Elephant birds — Madagascar natives consisting of at least four different species — are among the world's most massive birds. They were a towering 10 feet (3 m) tall and nearly 1,000 pounds, or 454 kilograms. (Note: male ostriches grow up to only 9 feet, or 2.7 m, tall.) Written records suggest the birds were around till at least the 17th century, and researchers think they were likely fully extinct by the early 18th century.

There are two main theories explaining the elephant birds' demise, both of which involve humans. Some researchers believe the birds fell to habitat loss and people stealing their eggs, which were 150 times the volume of a hen’s egg. Others think diseases carried over from settlers' chickens may have devastated the elephant bird populations.

(Editor's Note: This entry was updated to correct the metric conversion for the bird's height.)

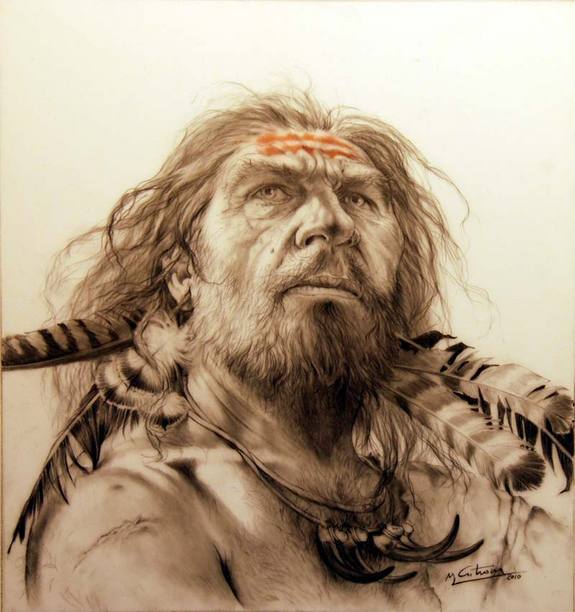

Neanderthals

No countdown about species extinctions is complete without mention of our hominid brethren, the Neanderthals. Why Neanderthals went extinct some 30,000 years ago is one of anthropology's greatest debates. At one point, scientists favored the idea that a "volcanic winter" — caused by a super-eruption combined with a sharp cold spell — killed the Neanderthals, who were unable to adapt to the climate change. But new research rules out the catastrophe hypothesis.

The real Neanderthal killers, then, were likely anatomically modern humans. Even still, there's no singular explanation. Could early humans have committed genocide? Maybe they just outcompeted Neanderthals? Or perhaps contact with other hominids introduced pathogens Neanderthals couldn't fight? And then there's the most romantic hypothesis (which actually has some genetic evidence to back it up): Neanderthals interbred with early humans, and that somehow led to their demise.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus