Giant Salamanders Strolled Onto Land Using Long Limbs

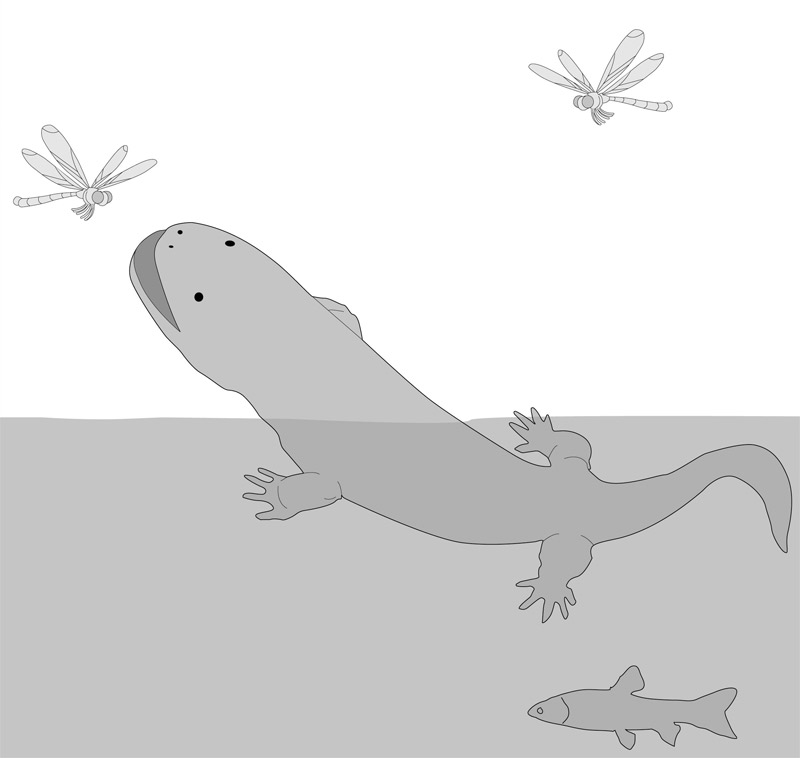

Modern giant salamanders live only in water, but their earliest, largest known ancestor, which had a burly head and lengthy limbs to boot, may have ventured onto land, researchers say.

Giant salamanders can grow up to 6 feet (2 meters) long and live up to 100 years. To learn more about the history of these Goliaths, which nowadays dwell in East Asia and North America, scientists analyzed the oldest known fossils of these creatures, 56-million-year-old specimens belonging to the extinct species Aviturus exsecratus from what is now the northwestern Gobi Desert in southern Mongolia.

Early giant salamanders were just as big as their modern counterparts, and judging by their anatomy, they often had similar lifestyles. Still, although modern giant salamanders prefer fast-flowing, oxygen-rich mountain streams, the sediments where the fossils of their ancestors have been discovered suggested they also lived in rivers and lakes in the lowlands.

Now researchers have found another major difference between ancient giant salamanders and their descendants — Aviturus exsecratus apparently was able to hunt on land as well as in water. [Album: Bizarre Frogs, Lizards and Salamanders]

Close analysis of four specimens of Aviturus exsecratus housed at the Moscow Paleontological Institute revealed this salamander had the longest limbs and heaviest skeleton of any giant salamander, features that would have helped it move on land. It also had the largest skull cavity devoted to smell of this group, a sense typically well-developed and useful for land-based species of salamanders. Moreover, Aviturus exsecratus had the strongest head muscles of any giant salamander, suggesting it went on land to hunt. Supporting this idea is the fact that fossil remains of this salamander were found in rock typically formed from water's-edge sediments.

Compared with its living brethren, this extinct giant went through extra stages of development. Modern giant salamanders essentially never grow up — while many "nongiant" salamanders eventually move on from the water, modern giant salamanders stay aquatic and keep many features seen in younger stages. Judging by the zigzag placement of its teeth, Aviturus exsecratus matured beyond the point its modern cousins reach, as smaller salamanders do today.

The researchers noted that giant salamanders first appeared during a brief period of global warming 55.8 million years ago, "the most sudden climate change since the death of the dinosaurs," researcher Davit Vasilyan, a vertebrate paleontologist at the University of Tübingen in Germany, told LiveScience. During this spike in heat, known as the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum, global temperatures rose by about 10 degrees Fahrenheit (6 degrees Celsius) within about 20,000 years.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Vasilyan suggested giant salamanders first appeared as terrestrial carnivores during this warm era. Later, when temperatures cooled, they stayed in the water and eventually abandoned later stages of development and terrestrial life, he said.

The scientists detailed their findings online Sept. 19 in the journal PLoS ONE.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus