Humans Behind Strongest Oklahoma Quake Ever Recorded, Research Suggests

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

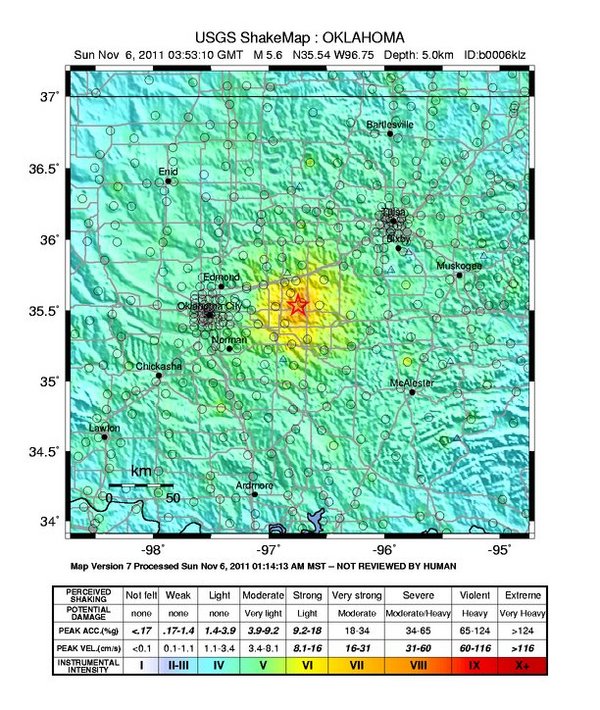

SAN DIEGO — On the night of Nov. 5, 2011, as midnight approached, a magnitude-5.6 earthquake rocked central Oklahoma, the state's most powerful quake ever recorded. The shaking injured two people, destroyed 14 homes, and bent a local stretch of highway.

Research presented here at the annual meeting of the Seismological Society of America today (April 18) suggests the quake could be related to an industrial practice of injecting fluids deep into the Earth.

"This is part of a growing number of cases of earthquakes caused by fluid injection — and if it was found to be linked, this would be the largest," said Steve Horton, a research scientist at the University of Memphis's Center for Earthquake Research and Information.

There are three wells within 3 miles (5 kilometers) of the main shock location that are actively injecting fluids nearly a mile (1.3 km) down into the subsurface, Horton told OurAmazingPlanet.

"They are not doing fracking," Horton emphasized. Fracking, or hydraulic fracturing, a practice used to extract natural gas from deep rocks, has been much in the national consciousness lately; some have tried to link the practice to earthquakes, though no such evidence has surfaced, said scientists gathered at the SSA.

"We simply do not see that there is a connection between hydrofracking and earthquakes that are of any concern to society," William Ellsworth, a seismologist with the U.S. Geological Survey said during a media briefing.

Instead of extracting materials from inside the Earth, the Oklahoma wells in question are designed to deliver fluids down into it. Fluid injection is used to get rid of industrial wastewater that might contaminate drinking water if it were disposed of at the surface, or to ease oil along through fractures in the Earth to a spot that is more accessible.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Horton said that although the area has a history of earthquake activity, there was a marked increase in the number of quakes in the two years leading up to the magnitude 5.6 earthquake. "This is similar to events we saw in the past where smaller events led up to a larger event," he said. [13 Crazy Earthquake Facts]

It's known that fluids that percolate down into otherwise tightly locked faults can essentially push the fault walls apart, allowing the fault boundary to suddenly jolt, yet earthquakes triggered by human geological tinkering are typically many tens of times smaller — in the magnitude-3 range.

Although the earthquakes occurred between 1.2 and 5 miles (2 and 8 km) depth — deeper than the wells reach — there is a good chance that fluid was able to travel down into the faults that ruptured by means of the Wilzetta Fault, Horton said, a known fault line that runs for more than 50 miles (80 km) across the state.

"We don't know for sure one way or the other, but it is possible the earthquake was triggered by the injections," Horton said. "It turns out that 95 percent of the earthquakes that have happened are within 10 kilometers [6 miles] of a well."

Horton's research found similar links between fluid injections of wastewater produced by hydrofracking in Arkansas and a spate of earthquakes in late 2010 and early 2011.

This story was provided by OurAmazingPlanet, a sister site to LiveScience. Follow OurAmazingPlanet for the latest in Earth science and exploration news on Twitter @OAPlanet and on Facebook.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus