Animation Captures Artful Swirl of Ocean Currents

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

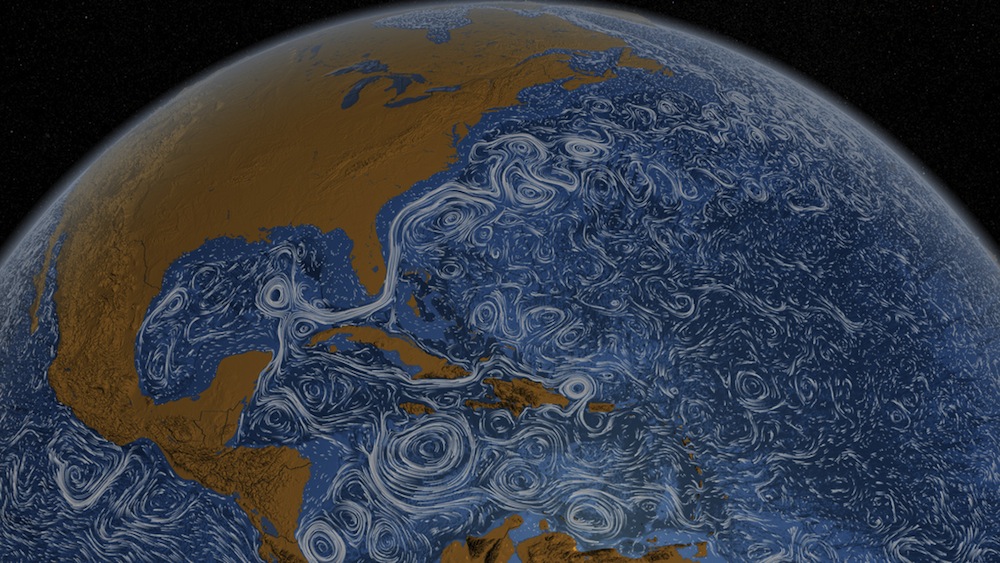

A NASA animation shows how ocean currents silently snake and swirl around the planet over the course of two and a half years, and in doing so reveals how science makes art and vice versa.

Fluid white lines represent currents, while the blue background is shaded to represent depth; the darker the background, the deeper the water. [Watch Perpetual Ocean Video]

The dreamy image illustrates current flow between June 2005 and December 2007, and is based upon a numerical model scientists use to simulate the movement of the ocean's surface.

Scientists have used observational data, such as measurements of sea-surface height made by satellites, to tweak the model and improve its results, said Dimitris Menemenlis, a satellite oceanographer at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory at the California Institute of Technology.

Menemenlis was one of the scientists whose work formed the basis for the animation, although he was not involved in creating it.

In addition to sea-surface height, NASA satellites orbiting Earth record ocean temperature, changes in gravitational pull (caused by the movement of water mass) and wind stress, which forms ripples on the surface of the water, he said.

A network of floating instruments, called Argo, also monitors temperature and salinity (salt level) profiles of the water. These influence the density of the water, and variations in density cause it to move, he said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The eddylike currents that show up throughout the illustration are the result of the Coriolis effect. The Earth's rotation deflects the motion of water (or air) that would otherwise be traveling in a straight line, and this effect produces circular currents.

Western boundary currents, part of basin-wide current patterns called gyres, are also visible. Fed by waters from the Gulf of Mexico, the Gulf Stream travels north along eastern North America, before heading toward Europe. Meanwhile, the Kuroshio current travels along the coast of Japan before heading east.

Illustrations like this can catch the eyes of nonscientists and future scientists, but there is also a scientific reason for creating them: They mayhelp researchers ask the right questions or get a broader perspective of a concept or phenomenon.

"We do generate massive amounts of numbers from the numerical models that describe the ocean, and they are very hard to look at," Menemenlis said. Animations, like this one, are one of the tools scientists use to understand the results of the models, he said.

Menemenlis uses the ocean current models to study how currents affect the melting of ice covering the Arctic Ocean, Antarctica and Greenland, as well as how quickly the ocean absorbs increasing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.

You can follow LiveScience writer Wynne Parry on Twitter @Wynne_Parry. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus