Black Holes' Fast-Moving Gas Clouds May Stifle Star Formation

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

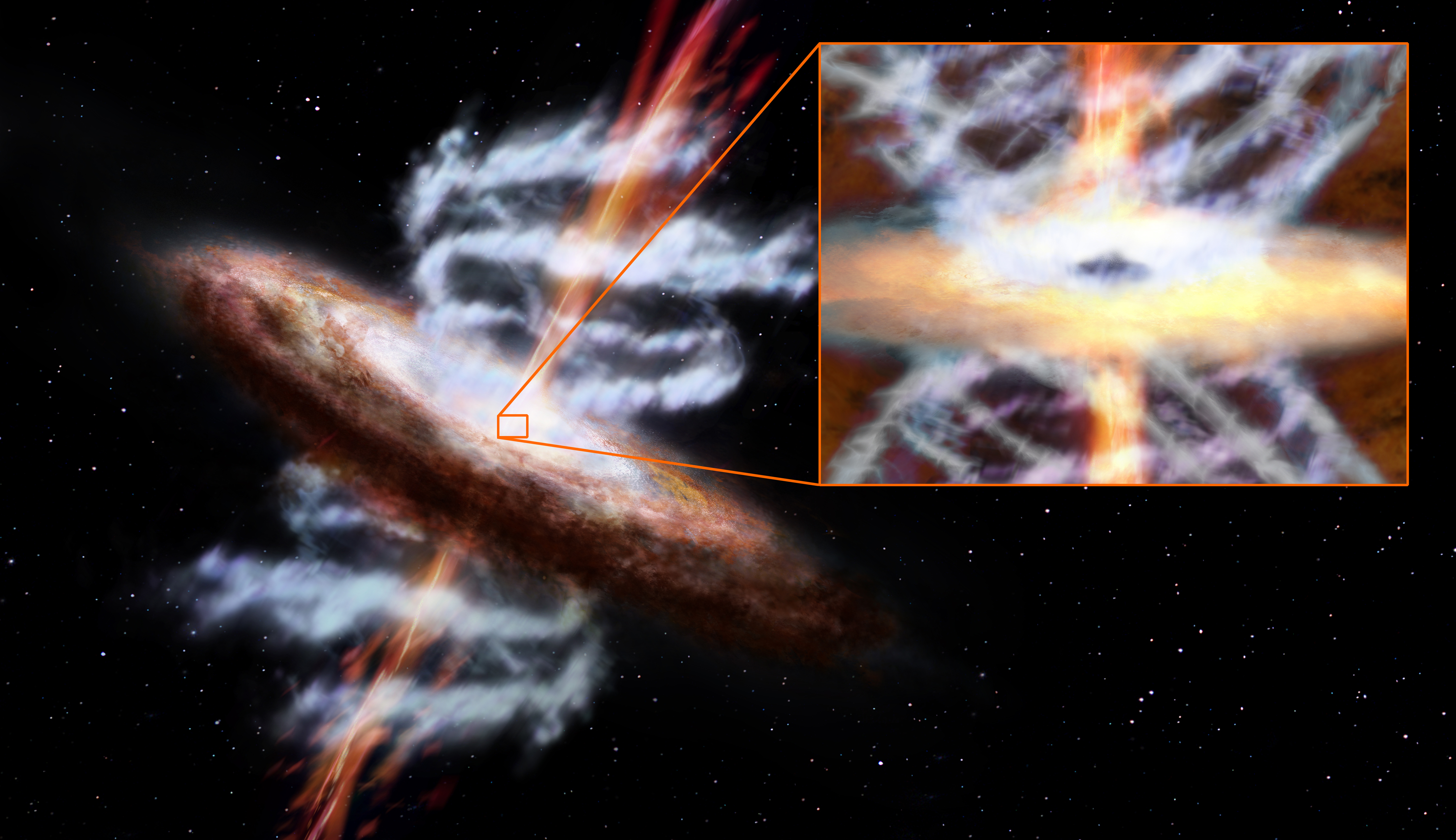

Newfound clouds of gas that stream from gigantic black holes may dictate the pace of star formation in the galaxies around them and the growth of the black holes themselves, according to a new study.

These outflows of gas appear to feed on matter that would otherwise fall into an expanding supermassive black hole, halting its growth. As they travel outward, the clouds may also sweep away the raw materials that form new stars in a vast, roughly spherical area known as the galaxy's bulge, slowing the pace of star formation in the process.

"They have the potential to play a major role in transmitting feedback effects from a black hole into the galaxy at large," study leader Francesco Tombesi, from NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md., said in a statement.

Most spiral galaxies, including our own Milky Way, are thought to contain supermassive black holes lurking in their centers.

The new observations of gas clouds around these black holes shed light on the strange and previously unexplained connection between the mass of a galaxy's central black hole and the velocity of stars in the galaxy's bulge, the researchers said.

"This was a real conundrum," Tombesi said. "Everything was pointing to supermassive black holes as somehow driving this connection, but only now are we beginning to understand how they do it."

Millions of suns

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Most central black holes inside galaxies are millions of times the mass of the sun. Galaxies that host more massive black holes, however, also possess bulges that contain, on average, faster-moving stars, the researchers said. [Images: Black Holes of the Universe]

Active black holes grow by gobbling up matter and gas in their surrounding disks. Near the edge of these accretion disks, a portion of the orbiting matter is blasted outward in particle jets, the researchers explained.

While these intense emissions have the power to hurl matter outward at half the speed of light, computer simulations have shown that the jets are narrow and the energy is carried beyond the galaxy's star-forming regions.

Astronomers have searched for the missing link, and over the last decade, evidence has surfaced for a new type of outflow that could explain how the behavior of a massive black hole, which affects a region several times larger than our solar system, could shape how stars are formed in a galaxy's bulge, which encompasses regions roughly a million times larger, the researchers said.

X-ray observations of active galaxies turned up intriguing results that showed particular wavelengths of radiation were being absorbed by something in front of the black holes — clouds of gas moving away from the center.

In two previously published studies, Tombesi and his colleagues indicated that these clouds represented a new and distinct type of black hole-driven outflow.

UFOs

To gain a clearer understanding of the location and properties of these so-called ultra-fast outflows (UFOs), researchers studied 42 nearby active galaxies using the European Space Agency's XMM-Newton satellite. The galaxies were all located less than 1.3 billion light-years away, and were selected from the All-Sky Slew Survey Catalog that was produced by NASA's Rossi X-ray Timing Explorer satellite.

Ultra-fast outflows were found in 40 percent of the studied galaxies, which suggests they are common in black-hole-powered galaxies, the researchers said.

"Although slower than particle jets, UFOs possess much faster speeds than other types of galactic outflows, which makes them much more powerful," Tombesi explained.

On average, the gas clouds were located less than one-tenth of a light-year away from the galaxies' central black holes, and moved at about 94 million mph (151 million kph), or about 14 percent the speed of light.

The scientists estimate that the outflows are made up of matter that is roughly equivalent to the mass of the sun, which is also comparable to the accretion rate of these black holes. The powerful outflows could also strip away the star-forming regions in the galaxy's bulge, which could slow or even shut down the formation of new stars.

If so, these ultra-fast clouds of gas could explain the observed connection between an active galaxy's black hole and its bulge of stars, the researchers said.

To build on these findings, the scientists intend to examine how these ultra-fast outflows came to be, which will also help them understand how active galaxies form, develop and grow. The results of the new study were published in the Feb. 27 issue of the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to LiveScience. Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus