Yeast Sex Life Gets Wild, Especially in Hard Times

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

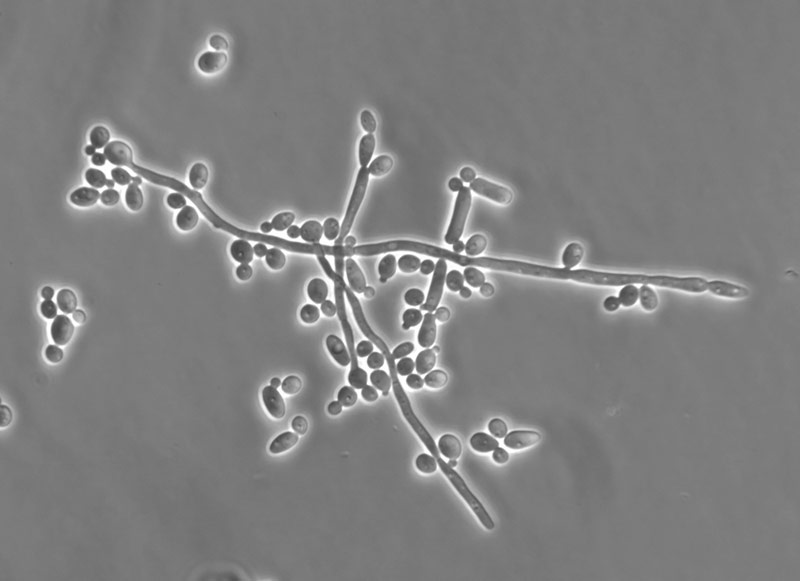

Voyeuristic scientists have caught yeast having sex, and lots of it, a finding that questions the assumed chastity of the microscopic fungi that cause yeast infections in humans.

Such sexual antics may explain how these yeast evolve into drug-resistant strains that are tricky to treat.

Most of the 1,500 known species of yeast, such as those involved in making breads and wines, primarily reproduce asexually through budding. Sexual reproduction is known to occur, but it is rare. The more harmful infectious yeast species, however, were thought to be exclusively asexual … until now.

Scientists at Brown University have discovered that Candida tropicalis, one of the multitudes of fungi living in and on the human body that can cause yeast infections, can mate selectively, creating new and potentially dangerous strains. The finding was reported on Dec. 5 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Graduate student Allison Porman discovered the yeast sex show during a rotation through the lab of Richard Bennett, an assistant professor of biology at Brown. Porman noticed that a white colony of C. tropicalis in a petri dish divided into lighter and darker regions, highlighting new combinations of genes, the telltale sign of mating. Asexual reproduction would have created genetic clones of the parents.

Bennett speculates this behavior is likely an evolutionary mechanism to better ensure the survival of their prodigy. "Sex is really good for microbes when times are hard," he said. "That's the time when you need to adapt and try various combinations of your genes."

The curious thing is, Bennett doesn't know what hard times trigger mating. Maybe it is heat, or maybe it is the scent of a particular pheromone released in response to stress. Bennett and his team now are attempting to uncover what gets yeast in the mood for mating to prove this theory of survival of the fittest.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

More than a prurient pursuit, the research has important repercussions of understanding drug resistance. The yeast's adaptability by switching sexual reproduction on and off could mean that it can evolve faster than what scientists had thought and thus is more capable of developing increased virulence and drug-resistant strains.

The ease at which C. tropicalis can reproduce sexually might imply that the practice among fungi is likely common. "I think the really asexual fungi are going to turn out to be the exception, rather than the rule," Bennett said.

Christopher Wanjek is the authorof the books "Bad Medicine" and "Food At Work." His column, Bad Medicine, appears regularly on LiveScience.

Christopher Wanjek is a Live Science contributor and a health and science writer. He is the author of three science books: Spacefarers (2020), Food at Work (2005) and Bad Medicine (2003). His "Food at Work" book and project, concerning workers' health, safety and productivity, was commissioned by the U.N.'s International Labor Organization. For Live Science, Christopher covers public health, nutrition and biology, and he has written extensively for The Washington Post and Sky & Telescope among others, as well as for the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, where he was a senior writer. Christopher holds a Master of Health degree from Harvard School of Public Health and a degree in journalism from Temple University.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus