Asian Ancestors Had Sex with Mysterious Human Cousins

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Neanderthals weren't the only ancient cousins that humans frequently mated with, according to a new study that finds that East Asian populations share genes with a mysterious archaic hominin species that lived in Siberia 40,000 years ago.

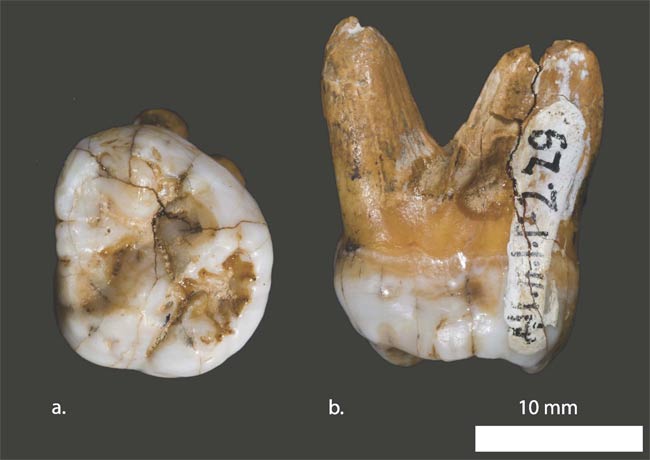

This group, the Denisovans, is known only by a few bone fragments: A finger bone, a tooth and possibly a toe bone, which is still undergoing analysis. The Denisovans likely split off from the Neanderthal branch of the hominin family tree about 300,000 years ago, but little else is known about their appearance, behavior or dress. But just as researchers have learned that ancient humans and Neanderthals mated, they've also found genetic echoes of the Denisovans in modern residents of Pacific islands, including New Guinea and the Philippines.

The new research expands the Denisovan genetic influence, uncovering Denisovan genes in modern East Asian populations. The genetic signal is less strong than it is in the Oceanic islands such as the Philippines, said study researcher Mattias Jakobsson, a professor of evolutionary biology at Uppsala University in Sweden. On the Asian mainland, the genetic similarities to Denisovans are strongest in southern China and Southeast Asia.

"We are actually finding gene flow in Southeast Asia," Jakobsson told LiveScience. "So it's not restricted to the Oceanian parts of the world."

Jakobsson and his colleagues first ran complex computer simulations of genetic data to understand how the limited gene information collected in population genetics research, which includes just segments of DNA, might be biased. With that understanding, the group then examined genetic data from more than 1,500 modern humans from all over the world.

Comparing that modern data with the Denisovan genome revealed that Asians, especially Southeast Asians, have a higher proportion of Denisovan-related gene variants than other world populations except for the Oceanic islanders. While Oceanians have about a 5 percent fraction of Denisovan-related ancestry, Southeast Asians have around 1 percent, the researchers report today (Oct. 31) in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. In comparison, genes from modern non-African humans have about a 2.5 percent fraction of Neanderthal ancestry.

It's hard to tell when the Denisovan and human interbreeding occurred, Jakobsson said, but since Europeans don't have Denisovan ancestry, it's likely the mating occurred around 23,000 to 45,000 years ago, after Southeast Asians and European populations diverged.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Jakobsson and his colleagues are working on further studies on early human genetics and the steps that led to the modern human genome. The more digging scientists do, the more complex the genetic picture becomes, he said. Notably, bits of genes are almost all that are left behind of some ancient populations, including the Denisovans, he said.

"We don't really know what they looked like, how they behaved or anything like that," Jakobsson said. "It's really genetics that gives us an edge here."

You can follow LiveScience senior writer Stephanie Pappas on Twitter @sipappas. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus