Paleo CSI: Early Hunters Left Mastodon Murder Weapon Behind

A new look at a very old mastodon skeleton has turned up evidence of the first known hunting weapon in North America, a tool made of bone that predates previously known hunting technology by 800 years.

The sharp bit of bone, found embedded in a mastodon rib unearthed in the 1970s, has long been controversial. Archaeologists have argued about both the date assigned to the bone — around 14,000 years old — and about whether the alleged weapon was really shaped by human hands. But now, researchers say it's likely that 13,800 years ago, hunters slaughtered elephant-like mastodons using bony projectile points not much bigger around than pencils, sharpened to needle-like tips.

"We're fortunate that the hunter 13,800 years ago was probably trying to get that bone projectile point in between the ribs, probably trying to get at a vital organ," said study researcher Michael Waters, an anthropologist at the Center for the Study of the First Americans at Texas A&M University. "Maybe the mastodon flinched or his thrust was off, and he hit a rib instead and broke his bone projectile point. So it's bad for him, and good for us." [Image Gallery: Evidence of Mastodon Hunters]

Waters and his colleagues report their finding in the journal Science tomorrow (Oct. 21).

Uncovering a kill site

One thing is for sure: The ancient mastodon kill wasn't a fair fight. The creature, unearthed by a rancher digging a stock tank in the late 1970s in Washington state, was old and likely sickly when it died, with teeth "quite literally worn down to a nubbin," said Donald Grayson, an anthropologist at the University of Washington who was not involved in the new study.

The rancher turned the site over to archaeologists, who returned the favor by dubbing the find the "Manis Mastodon," the rancher's surname. The archaeologist's claim that the mastodon was hunted down by humans about 14,000 years ago was regarded with suspicion among other researchers, however, who pointed out that there was no solid proof that the bony point found embedded in the mastodon bone was made by human hands.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

It was possible, Grayson said, that the bone was a part of the mastodon's own skeleton, perhaps even a dislodged bone chip from a fight with another animal. [Read: 25 Amazing Ancient Beasts]

Paleo cold case

But archaeological technology today is leaps and bounds past what it was in the 1970s. So Waters and his colleagues decided to take another look at the case of the Manis Mastodon. They extracted bone protein from the damaged rib and radiocarbon-dated it, an advanced version of the dating technique used four decades ago. Sure enough, they found that the specimen dates back 13,800 years. That's 800 years earlier than the North American Clovis, who were known to hunt mammoths and mastodons.

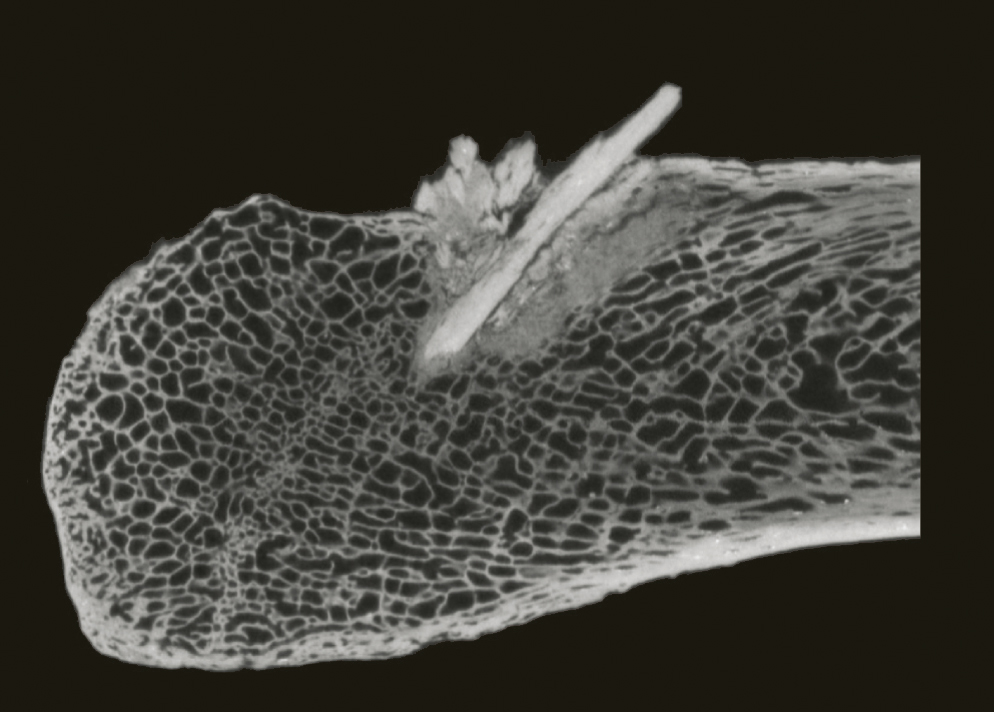

But Waters and his colleagues also needed evidence that the bony tip embedded in the rib was man-made. To investigate, they used a high-resolution computed tomography (CT) scan.

"We're all familiar with hospital CT scanners where they can scan your body and look inside to see organs and bones," Waters said. "This is a high-resolution industrial version that creates digital X-rays spaced every 0.06 millimeters [0.002 inches], about half the thickness of a piece of paper."

This ultra-sharp look inside the rib revealed the needle-sharp shaft of the projectile point lodged inside the mastodon's bone. The images suggested the point had been whittled down and sharpened, Waters said, the work of human hands. [See video of the weapon point and bone]

To top it off, the researchers extracted bone protein and DNA from the projectile point itself, determining that the weapon had been made from the bones of yet another mastodon.

"That was even more exciting, because what that meant is whoever these hunters were that tracked down and killed the Manis Mastodon were hunting with weapons made from a previous kill," Waters said.

Pre-Clovis hunters

Other anthropologists warned that it's difficult to conclusively understand an archaeological site given only one artifact, but said the find went a long way to putting the mastodon controversy to bed.

"It's very convincing," said James Dixon, the director of the Maxwell Museum of Anthropology at the University of New Mexico, who was not involved in the current study. Other mammoth and mastodon butchering sites from the same time period have been discovered (albeit without hunting weapons), Dixon said, and the new mastodon analysis adds to the evidence that human hunter-gatherers were killing the big, woolly creatures before the Clovis culture came along.

"To me, the high-quality scan strongly suggests that this really is a bone projectile point, and that this is another pre-Clovis site," Grayson agreed. If so, he said, it's the third confirmed pre-Clovis archaeological site, including the northern Patagonia settlement of Monte Verde from about 14,800 years ago and the Paisley Caves in Oregon, where scientists uncovered 14,300-year-old human feces.

So how did these early hunters kill a creature the size of an elephant with weapons the size of pencils? It's possible that groups of hunters ganged up on a mastodon and threw their projectile points like spears until the animal looked "like a pincushion," Waters said. The Manis Mastodon was nicked in an upper rib, consistent with the use of an atlatl, or spear-thrower, a hollowed-out shaft used to get more speed and leverage behind a thrown spear, Dixon said.

Or maybe that mastodon was already on its last legs before the human hunters finished it off, Grayson suggested.

"It is fully possible that this poor guy was not standing when killed, and might actually have been lying down and in the process of dying on his own," Grayson said. "That would solve the problem of having someone tall enough, or up high enough, to stick it in the back."

You can follow LiveScience senior writer Stephanie Pappas on Twitter @sipappas. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus