Earth's First Arctic Ozone Hole Recorded

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

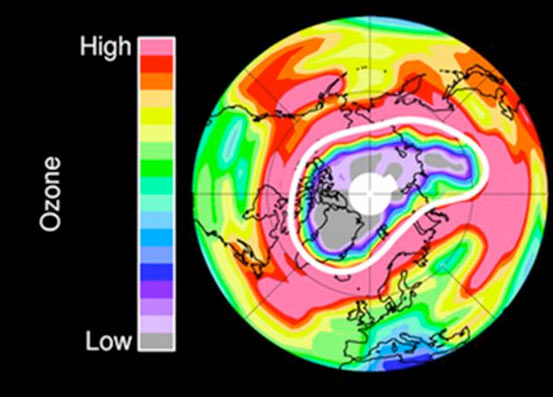

The high atmosphere over the Arctic lost an unprecedented amount of its protective ozone earlier this year, so much that conditions echoed the infamous ozone hole that forms annually over the opposite side of the planet, the Antarctic, scientists say.

"For the first time, sufficient loss occurred to reasonably be described as an Arctic ozone hole," write researchers in an article released Oct. 2 by the journal Nature.

Some degree of ozone loss above the Arctic, and the formation of the Antarctic ozone hole, are annual events during the poles' respective winters. They are driven by a combination of cold temperatures and lingering ozone-depleting pollutants. [North vs. South Poles: 10 Wild Differences]

The reactions that convert less reactive chemicals into ozone-destroying ones take place within what is known as the polar vortex, an atmospheric circulation pattern created by the rotation of the Earth and cold temperatures. This past winter and spring saw an unusually strong polar vortex and an unusually long cold period.

This year's record vortex persisted over the Arctic from December to the end of March, and the cold temperatures extended down to a remarkably low altitude, the researchers write.

At altitudes of about 11 to 12 miles (18 to 20 kilometers), more than 80 percent of the ozone present in January had been chemically destroyed by late March.

The same dynamics create the infamous ozone hole over Antarctica. But above the South Pole, ozone is essentially completely removed from the lower stratosphere ever year. Above the North Pole, however, ozone loss is highly variable and has, until now, been much more limited, writes the international research team led by Gloria Manney of the California Institute of Technology.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Countries agreed to end their production of the substances ultimately responsible for destruction of the ozone in 1987 with the Montreal Protocol. However, these pollutants, including chlorofluorocarbons, still linger in the atmosphere. Ozone loss is expected to improve in the coming decades as atmospheric levels of these chemicals decline.

On the Earth's surface, ozone is a pollutant, but in the stratosphere it forms a protective layer that reflects ultraviolet radiation back out into space. Ultraviolet rays can damage DNA and lead to skin cancer and other problems.

Global warming is implicated in the loss of Arctic ozone because greenhouse gases trap energy lower down, heating up the atmosphere nearer the ground but cooling the stratosphere, creating conditions conducive to the formation of the reactive chemicals that break apart the three-oxygen molecules of ozone.

You can follow LiveScience writer Wynne Parry on Twitter @Wynne_Parry. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus