Friend or Foe? The Colon Knows 'Good' Bacteria From 'Bad'

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

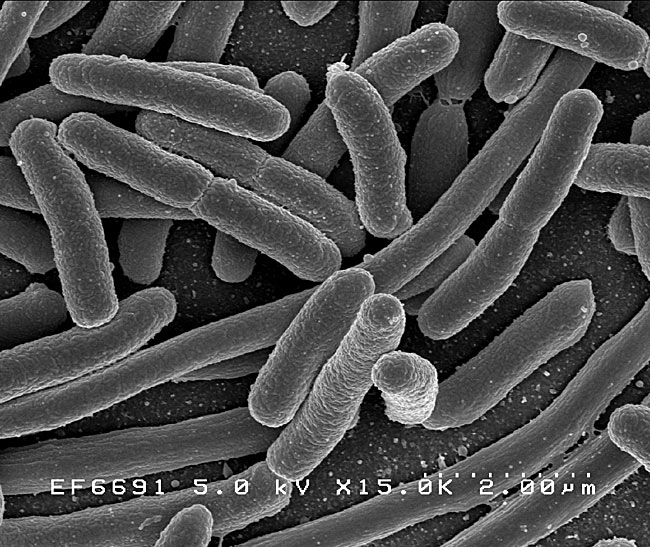

The human gut is teeming with bacteria, most of which helps us digest food and fend off the bad guys in the belly. But how does the body tell the good from the bad?

New research is pointing to gut-specific white blood cells (called Treg cells), which "learn" to identify and then protect the good gut bacteria, telling our bodies "Don't mess with them."

"Since we've had these microbes living with us for the millennia, we've developed a tolerance to them," said Josef Neu, a researcher from the University of Florida who wasn't involved in the study. "That same tolerance with those Treg cells helps prevent us from getting certain types of diseases, like colitis."

The study, led by Chyi-Song Hsieh, of Washington University School of Medicine, in St. Louis, looked at the white blood cells present in the guts of lab mice. They saw that the gut naturally has its own population of the Treg cells which protect friendly gut bacteria.

These protecting cells must rely on some common factor shared by foreign (yet friendly) gut bacteria as well as our own gut cells. If that's the case, Neu speculated what would happen if the protector cells weren't around when our immune system was developing, saying if those bacteria aren't there, the body could react badly to our normal cells.

"I would go on to speculate that this may be one of the first steps that might help us determine if there are individual types of microbes that we could utilize to help develop tolerance to self," Neu told LiveScience.

For instance, an autoimmune gut disease like Crohn's or celiac disease could be treated by exposing the patient's immune system to the right kind of bacteria. Exposure to these protector microbes might temper the immune system so that it stops attacking similar proteins in the body and destroying its own cells.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

A researcher who wasn't involved in the study, Fagarasan Sidonia from the RIKEN Research Center for Allergy and Immunology in Kanagawa Japan, told LiveScience in an email that the study "is an interesting piece of work that raises more questions than answers," but has some reservations about the work.

"I am almost convinced that there are Tregs [the gut-specific white blood cells] induced in the gut," she said. "But what remains unclear is how many in normal circumstances and their functional properties — which are not answered by this paper."

The study will be published in the Sept 22 issue of the journal Nature. Though mice serve as good biological models for humans, the researchers can't be sure the same holds true in us and further testing is necessary.

You can follow LiveScience staff writer Jennifer Welsh on Twitter @microbelover. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Jennifer Welsh is a Connecticut-based science writer and editor and a regular contributor to Live Science. She also has several years of bench work in cancer research and anti-viral drug discovery under her belt. She has previously written for Science News, VerywellHealth, The Scientist, Discover Magazine, WIRED Science, and Business Insider.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus