Arctic Sea Ice Hits Record Low, According to One Measure

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

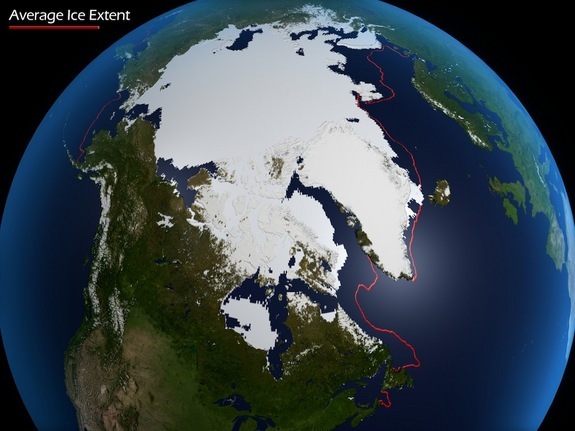

One of the harbingers of global climate change — the extent of the Arctic sea ice — has passed a new threshold. German researchers announced on Sept. 8 that the sea-ice cover had shrunk below its record minimum, set in 2007.

Or has it? Elsewhere, researchers said the race remained too close to call.

"The present year and 2007 are tracking very closely by anybody's measure," said Ted Scambos, senior research scientist at the National Snow and Ice Data Center at the University of Colordo, which also tracks the extent of Arctic sea ice. [Album: Glaciers Before & After Climate Change]

The NSIDC proclaimed the record low on Sept. 16, 2007, when it measured the extent of the ice at 1.59 million square miles (4.13 million square kilometers), about 1 million square miles (2.69 million square kilometers) below the average for 1979 to 2000. NSIDC scientists said the 2007 record was the result of a perfect storm — including fewer clouds that allowed sunlight to melt the ice, and winds that shoved the ice together — that brought the ice to a new minimum. While temperatures were warm this year, other conditions were more typical.

"The main message is not so much whether or not we set a record, but this year, without any noticeably unusual pattern of weather, we nearly broke a record, which only four years ago took a very unusual weather pattern plus a warming Arctic to achieve," Scambos said.

This is evidence that Arctic ice is continuing to thin and the Arctic is continuing to warm, he said.

Sea ice and climate change

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Unlike the Antarctic, there is no continent atop the northern Arctic, which remains at least somewhat ice covered year-round. This ice cover expands during the winter, hitting its greatest seasonal extent in March, then waning after summer's warmth and hitting its lowest extent in September.

A consistent record of its extent, based on measurements taken from sensors on satellites, began in 1979.

Recent years have brought record lows to the September minimum, and the March maximum has declined as well. Scientists blame a combination of natural variation and human-caused climate change.

Sea ice should have ups and downs brought on by natural forces — like the extreme wind and cloud conditions that helped bring ice to a new low in 2007 — but these natural causes should, in theory, balance themselves out over time, according to Walt Meier, a research scientist at NSIDC.

However, our emission of greenhouse gases, which keep energy within the Earth's atmosphere, rather than allowing it to escape into space, alters the long-term trend, Meier said.

"With greenhouse gases we have loaded the dice, what used to be a warm summer that would happen only once is now becoming normal, an average summer. And we are seeing that what used to be a cold summer doesn’t really happen anymore," he said.

Although data on it are difficult to collect, scientists believe that the thickness of Arctic ice is an important indicator of melt. It appears older, thicker ice is disappearing, leaving thinner ice that is more susceptible to melt, according to Meier. The older, thicker ice cover has continued to decrease since 2007, he said.

The implications are numerous. Receding sea-ice cover can disrupt indigenous people's way of life and threaten animals like polar bears and walruses. The loss of the "refrigerator" on top of the world can alter weather patterns elsewhere in the world. And once ice is lost it becomes more difficult to replace because light can then reach the ocean, which absorbs it and warms. [The World's Weirdest Weather]

Different data

Both the NSIDC and the researchers from the University of Bremen in Germany use data collected by sensors on satellites that pick up on microwave radiation emanating from the Earth; however, the Bremen group uses a sensor that can detect ice cover at a higher resolution, Scambos said.

While NSIDC sensors can look at ice cover in areas of about 15.6 miles (25 kilometers) across, the sensor used by researchers at Bremen can see areas about 3.9 miles (6.25 km) across, and this allows them to draw a more detailed map that takes into account holes in the ice and ragged edges, Scambos said.

"It's a mixed bag," Scambos said. "In some ways it makes it more accurate, because they can see these relatively small holes in the ice, but they are also more susceptible to melting and storm effects" — meaning Bremen's sensor data can be altered by melting snow or water on top of ice or by storms, he said. "None of them are perfect (but) we all show the broader picture very clearly."

NSIDC's continuous measurements go back to 1979, longer than the data collected from sensors the German group is using, according to Scambos. When determining if a record has been set, it is important to use the longest-running, validated records, he said. [Arctic Sea Ice at Lowest Point in Millennia]

You can follow LiveScience writer Wynne Parry on Twitter @Wynne_Parry. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus