How to Mask a High-Speed Land Rover? Paint it Like a Zebra

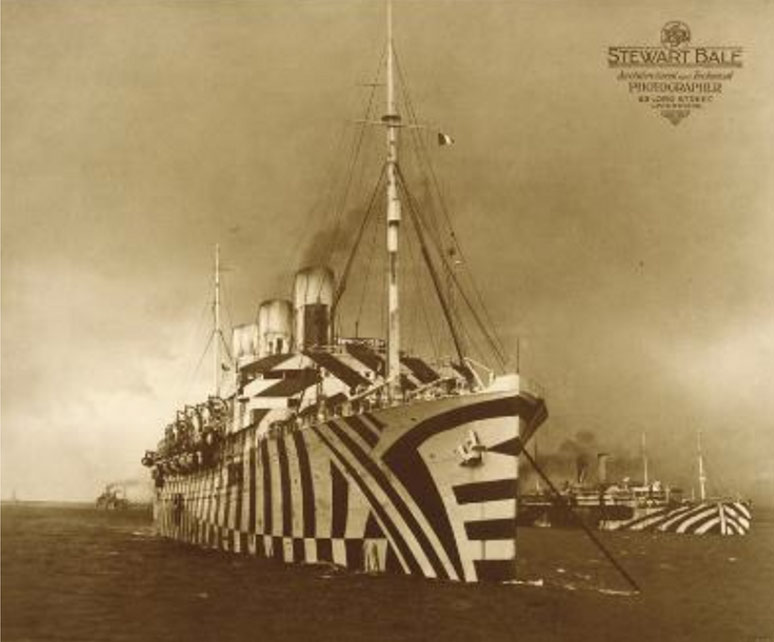

Like 50,000-ton zebras, battleships from both world wars were painted with high-contrast geometric patterns. The safari stripes were an optical illusion meant to confuse the enemy as to a ship's whereabouts and speed.

New research finds the patterns probably didn't help the slow-moving ships hide their speed, but similar geometric patterns could help distort the view of fast-moving objects, the researchers say. Think Land Rovers covered in black-and-white zigzags.

Camouflage is usually used to conceal objects, by matching their color and patterns to the background. This becomes an issue when the object is moving through its environment, like a ship or tank. "Dazzle" camouflage works in a different way, its aim to confuse and bewilder the onlooker so they can't determine the size, speed and heading of the object. [Eye Tricks: Gallery of Visual Illusions]

"They didn't need to conceal the ship, they wanted to confuse the enemy," said study researcher Nicholas Scott-Samuel of the University of Bristol in the United Kingdom. "It's fairly counterintuitive."

Dazzling difference

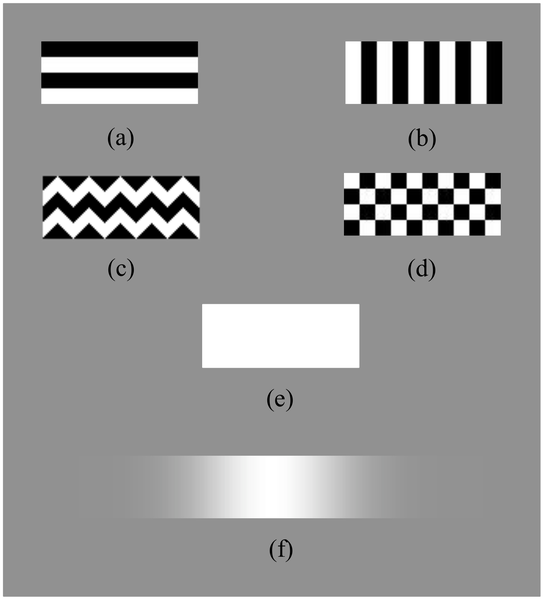

Dazzle camouflage is usually composed of high-contrast colors, like black and white, arranged in geometric patterns.

This patterning on World War I and II battleships was meant to throw off the aim of enemy ships, whose rangefinders used images from two locations to calculate the distance to an object; repetitive geometric designs made it difficult to line up the two images correctly, meaning the enemy's targeting would likely be off. As range-finding improved, these tactics became less effective but it was still assumed that the patterns might confuse other perceptions of the ship, like how fast it was going.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

To determine if this was true, Scott-Samuel and his colleagues had participants indicate which of two shapes with different patterns was moving faster. They did this for a series of image pairs. They tended to judge the zigzag and checked patterns as moving about 7 percent slower than the other patterns (such as horizontal or vertical stripes), but only when the shapes were moving at high speed (the equivalent of 8 miles per hour, or 13 kilometers per hour, from an observer 33 feet, or 10 meters, away).

Three feet for survival

Extrapolating what they found in the lab, the researchers said this would cause about a 3-foot (1 meter) aiming error of a rocket-propelled grenade launched at a fast-moving object, like a Land Rover driving 55 miles per hour (90 kph) from 230 feet (70 m) away, enough to save the lives of anyone riding in it.

"These situations are less common these days, but possibly when you have firefight, direct visual contact, that's when it would be useful," Scott-Samuel said.

This effect could also be why zebras have high-contrast striping, which hinder their predators' ability to track them and make it harder to tell an individual apart from the herd.

The study was published June 1 in the journal PLoS ONE.

You can follow LiveScience staff writer Jennifer Welsh on Twitter @microbelover. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Jennifer Welsh is a Connecticut-based science writer and editor and a regular contributor to Live Science. She also has several years of bench work in cancer research and anti-viral drug discovery under her belt. She has previously written for Science News, VerywellHealth, The Scientist, Discover Magazine, WIRED Science, and Business Insider.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus