World's biggest underwater eruption birthed skyscraper-size volcano

It's hanging out underwater near Madagascar.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

In 2018, the largest active underwater eruption ever recorded birthed a giant "baby": a skyscraper-size underwater volcano, a new study finds.

Scientists discovered the 2,690-foot-tall (820 meters) volcano in the western Indian Ocean, off Madagascar, following a puzzling spate of earthquakes that struck near what is normally a seismically quiet area. After collecting geological data, including information from a 2019 underwater survey of the region, the team realized that there was a new submarine volcano about 1.5 times the height of New York's One World Trade Center. What's more, this new "baby" draws from the deepest volcanic magma reservoir known to scientists.

"The source of the magma, the reservoir, is very deep" — about 34 miles (55 kilometers) underground, study lead researcher Nathalie Feuillet, a marine geoscientist at the Paris Institute of Earth Physics (IPGP) - University of Paris, told Live Science. "This is the first time in volcanology that we can see such a deep reservoir at the base of the lithosphere," the outer shell of Earth that includes the upper mantle and crust.

Related: Photos: Fiery lava from Kilauea volcano erupts on Hawaii's Big Island

Between May 2018 and May 2021, more than 11,000 detectable earthquakes shook Mayotte, a small island and French territory between Madagascar and Mozambique. The most powerful earthquake was a magnitude 5.9, but there were also strange seismic hums, or very-low-frequency earthquakes, that originated deep underground; they couldn't be felt at the surface but were picked up by seismometers around the world. These very-low-frequency earthquakes are associated with volcanic activity.

This sudden seismic activity was surprising, given that only two earthquakes have been detected near Mayotte since 1972 and, until now, the most recent volcanic activity — a layer of pumice in a lagoon near the island — was left at least 4,000 years ago, the researchers wrote in the study.

In July 2018, scientists realized that Mayotte was moving eastward at about 7.8 inches (20 centimeters) a year, according to GPS data. At that point in time, the island had only three or four GPS stations, so scientists installed global navigation satellite systems and ocean-bottom seismometers around the island to learn more about the geological changes occurring there. The findings were extraordinary: The combined land and ocean-bottom seismometers picked up 17,000 events between February and May 2019, the researchers found.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Sea voyage

In May 2019, Feuillet and her colleagues had the opportunity to go on a voyage aboard the research vessel Marion Dufresne. The team knew there had been a magmatic event east of Mayotte, but they weren't sure if the magma had stayed deep under the crust or if it had erupted onto the seafloor.

"We expected to see something, but it was not certain," Feuillet said.

In a 2019 post, she wrote, "On board, we put in place a protocol to analyse the seismic signals recorded by the OBS [ocean-bottom seismometers]. The teams operated around the clock, broken down into shifts, and we were able to precisely locate, in less than 2 weeks, the nearly 800 largest earthquakes (of magnitudes between 3.5 and 4.9)."

Their efforts paid off: "We discovered that these earthquakes were, for the most part, located in an area quite close to the island (10 km [6 miles] from the east coast of the island) but were deep (between 20 and 50 km [12 to 31 miles] deep)," Feuillet wrote.

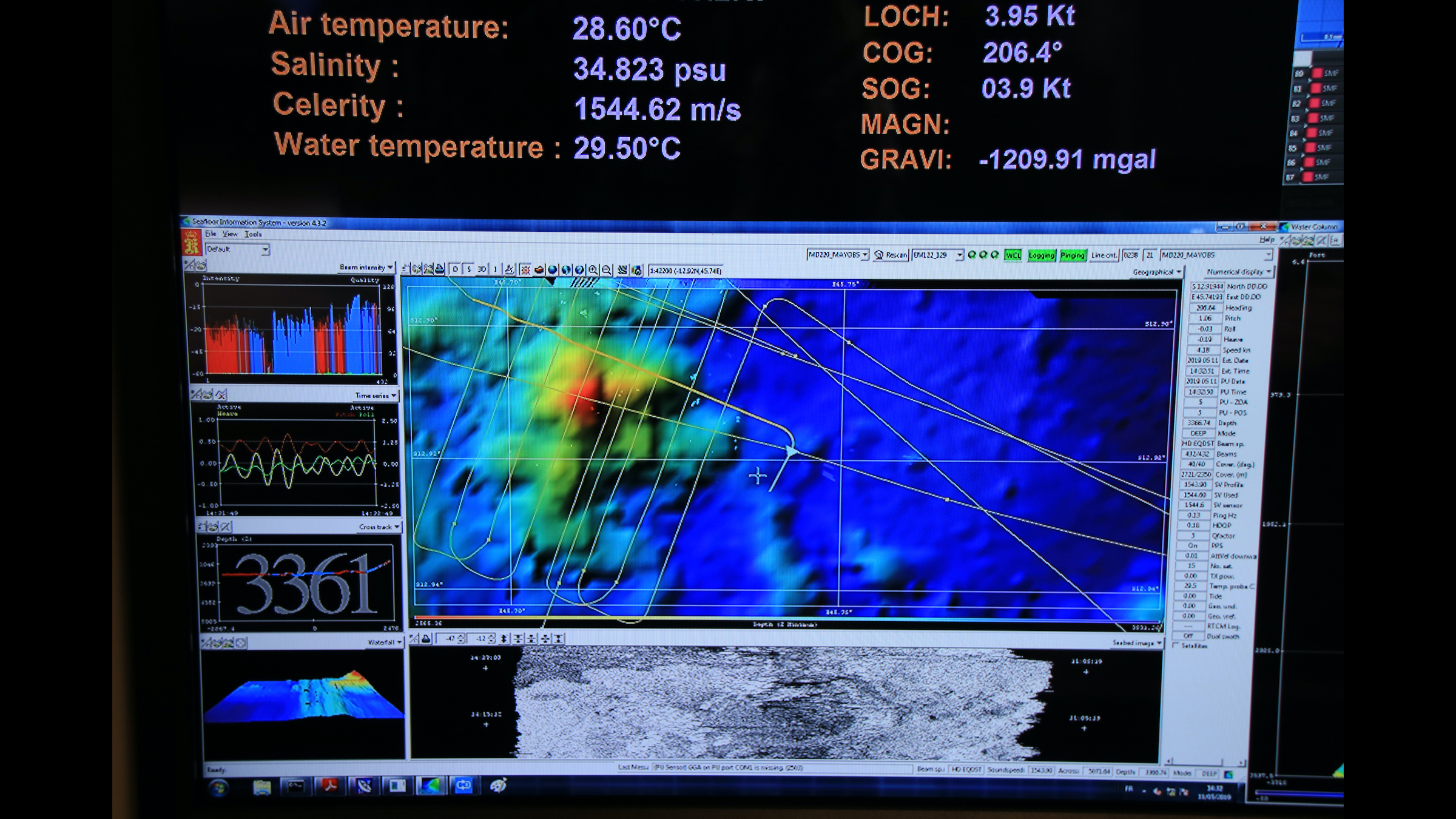

Then, the vessel's multibeam echo sounder, which sends out sound waves to map the seafloor and water column, found something "very big" about 31 miles east of Mayotte, Feuillet said. It was an underwater volcano with a pyramid-shaped edifice measuring about 1.2 cubic miles (5 cubic km). This volcano was completely new; it wasn't there in 2014, according to the previous survey by France's Naval Hydrographic and Oceanographic Service.

According to the 2014 survey, that area was "almost flat at around 3,300 m [10,827 feet] below sea level," the researchers wrote in the study. As of May 2019, the newly minted volcano's summit rose to 8,465 feet (2,580 m) below sea level.

The volume of material that this volcano spawned is 30 to 1,000 times larger than other documented deep-sea eruptions. It's more than three times larger than the 2012 Havre eruption in New Zealand and 2.5 times larger than the 2014 Bardarbunga eruption in Iceland, which was Iceland's largest eruption in the past 200 years.

It appears that plate tectonic movement led lava in the asthenosphere, the upper layer of the mantle directly below the rigid lithosphere, to move upward. This magma flowed upward in geologic dikes, which could explain the earthquakes and the subsequent massive eruption.

What's more, this eruption doesn't appear to be the first one near Mayotte. "Large lava flows and cones on the upper slope and onshore Mayotte indicate that this has occurred in the past," the researchers wrote in the study.

The team is monitoring the region for more earthquakes and volcanic activity. "It's still erupting," Feuillet said. "The last evidence for lava at the seafloor was in January 2021."

The study was published online Aug. 26 in the journal Nature Geoscience.

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus