New, Weird Fungus Lurks Around Globe

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

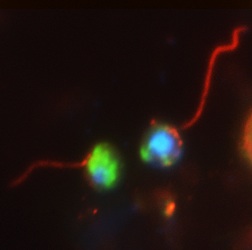

A strange group of fungi with soft bodies instead of rigid cell walls has now been discovered all over the world.

Discovering fungi without these hard structures would be akin to finding humans without any bones, the researchers explained.

These enigmas have been found lurking in a wide variety of habitats as diverse as cornfields, marine sludge, polluted landfills, sulfurous springs and freshwater ponds. The specimens that researchers have captured so far suggest they are as genetically diverse as the rest of the known fungi, but much remains unknown about their structure and behavior.

"The diversity of fungi is much more complex than we previously thought," researcher Thomas Richards, an evolutionary biologist at the University of Exeter in England, told LiveScience.

The mysterious nature of these organisms has granted them the name "cryptomycota," which is Greek for "hidden fungi." Richards and his colleagues first spotted the odd fungi in a pond at the University of Exeter, and after analyzing snippets of DNA from other environments, they realized an untapped diversity of fungi might exist in nature.

Although fungi were long considered plants, genetic studies have revealed they are actually more closely related to animals. Fungi typically feed by secreting digestive enzymes into the environment and slurping up their meals, and are the main way biological matter on land, such as dead plants and animals, is broken down and recycled.

Genetic analysis shows the cryptomycota are definitely fungi. However, bizarrely, unlike all known fungi until now, they lack cell walls made of chitin, the same material that makes up crustacean and insect shells. These chitinous structures were thought to make fungi as successful as they have proven — their toughness helps fungi resist the high pressures that come into play when they such up their liquified food.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"The evolution of the fungal cell wall was thought to be the key to the evolutionary success of the fungi," Richards said. But "cryptomycota seem to have done well without using this character in key life-cycle stages."

The cryptomycota that researchers have uncovered so far are all just 3 to 5 microns or so long (a human hair is about 100 microns wide) and are each capable of forming a single whiplike flagellum, which they use to swim.

They likely fill an extreme diversity of roles in ecosystems, such as parasites and symbionts, which form partnerships with a host as a one-way street where the fungus takes without providing, or as a two-way partnership.

"The huge genetic diversity and prevalence of this group leads us to believe they probably play an important role in a range of environmental processes," said researcher Meredith Jones at the University of Exeter. "It is possible there are many different forms of this organism with a range of characteristics we don't even know about yet. There is a lot more research to be done to establish how they feed, reproduce, grow, and their importance in natural ecosystems."

These hidden fungi have apparently escaped detection until now because of their microscopic size and the fact that they don't grow in labs as readily as their more familiar relatives. Even now, much remains unknown about their life cycle and what structures they might form.

Researchers suspect the cryptomycota evolved early as part of the primary branch of the fungus family tree and so may reveal what the first fungi looked like. [Read: Prehistoric Mystery Organism a Humongous Fungus]

"Fungi have been well studied for 150 years and it was thought we had a good understanding of the major evolutionary groups, but these findings have changed that radically," Richards said. "Current understanding of fungal diversity turns out to be only half the story — we've discovered this diverse and deep evolutionary branch in fungi that has remained hidden all this time."

The scientists detailed their findings online today (May 11) in the journal Nature.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus