Schizophrenic Simulation: Computer Acts Out Human Disease

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

A computer that claims responsibility for a terrorist bombing might typically be cause for alarm, but one particular computer's delusional tale delighted researchers at the University of Texas at Austin. The computer's neural network had successfully mimicked the strange stories of schizophrenic patients by having an abnormally high learning rate.

That case of virtual schizophrenia gave support to a new theory about how schizophrenic patients lose the ability to forget irrelevant details or filter information in meaningful ways. The inability to forget may lead the brain to form false connections -- such as finding secret CIA messages in newspaper stories about Osama bin Laden's killing — or create completely incoherent views of reality.

A brain chemical called dopamine may help encode what counts as relevant information in the human brain, researchers say.

"If we say that dopamine controls the intensity of memory learning and consolidation, we can simulate that by intensifying the learning in the neural network," said Uli Grasemann, a graduate student in computer science at the University of Texas at Austin.

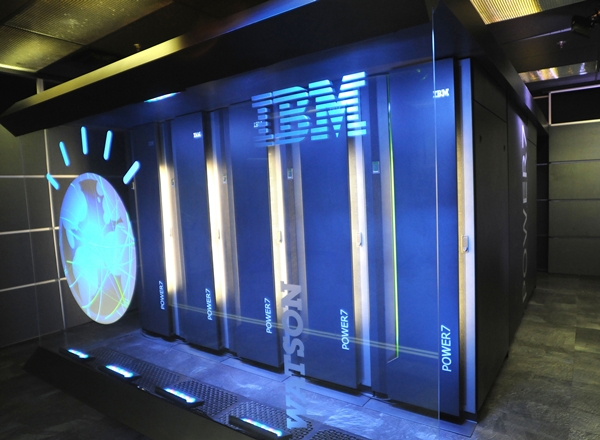

Grasemann used a neural network, called DISCERN, which can learn natural languages. DISCERN can also remember simple stories, such as the sequence of events from going to eat at a restaurant. It processes grammar and can follow basic scripts to follow the overall structure of stories.

"You tell it stories and it remembers those stories in a way that is hopefully how humans remember and encode stories in memory, and then it tells those stories back at you," Grasemann told InnovationNewsDaily.

The University of Texas researchers tried simulating many different types of brain damage in DISCERN, in hopes of finding the mechanism behind schizophrenia. But they only hit the jackpot when they elevated DISCERN's learning rates so that it did not forget at normal rates.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

That disruption to the neural network's memory process not only resulted in the terrorist story claim, but also led to the disordered behavior known as "derailment." In those cases, DISCERN responded to requests for specific memories by spewing out a jumble of grammatically correct yet disassociated sentences, making abrupt digressions and leaping back and forth from first- to third-person.

Simulation results were compared to the language and narrative patterns of human schizophrenics by Ralph Hoffman, professor of psychiatry at the Yale University. The hyperlearning tests gave the closest matches between the schizophrenic computer and humans.

Grasemann hopes to keep tuning DISCERN alongside its creator, Risto Miikkulainen, professor of computer sciences and neuroscience at the University of Texas. By pinpointing possible mechanisms for schizophrenia, the neural network simulations may encourage researchers to begin looking for direct clinical proof in schizophrenic patients.

"You can't really prove anything with a computer model like this," Grasemann said. "What you can get is a convenient and powerful way of expressing hypotheses. Then you go back to the clinical research."

The study is detailed in the April issue of the journal Biological Psychiatry.

Follow InnovationNewsDaily on Twitter@News_Innovation, or on Facebook.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus