World's Plants Growing Less Thanks to Warming, Drought

The world's plants are growing less than they did in recent decades, thanks to the stress of droughts, a new study finds.

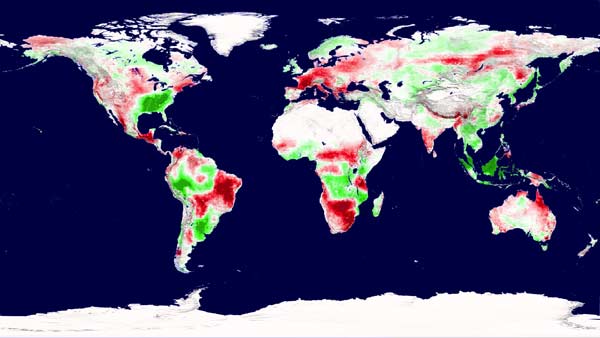

NASA satellites were used to measure global plant productivity over the last 10 years and found that growth was on the decline, after plants flourished under warming temperatures and a lengthened growing season in prior years.

The decrease was relatively minor — compared with a 6-percent increase spanning two earlier decades, the recent 10-year decline was just 1 percent — but it could impact food security, biofuels, and the global carbon cycle.

"We see this as a bit of a surprise, and potentially significant on a policy level because previous interpretations suggested that global warming might actually help plant growth around the world," said study researcher Steven Running, of the University of Montana in Missoula.

Conventional wisdom based on previous research held that land plant productivity was on the rise. A 2003 paper in Science led by then University of Montana scientist Ramakrishna Nemani (now at NASA Ames Research Center in Moffett Field, Calif.) showed that global terrestrial plant productivity increased by as much as 6 percent between 1982 and 1999. That's because for nearly two decades, temperature, solar radiation and water availability — influenced by climate change — were favorable for growth.

Setting out to update that analysis, Running and his UM colleague Maosheng Zhao expected to see similar results as global average temperatures have continued to climb. Instead, they found that the impact of regional drought overwhelmed the positive influence of a longer growing season, driving down global plant productivity between 2000 and 2009.

"This is a pretty serious warning that warmer temperatures are not going to endlessly improve plant growth," Running said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The discovery comes from an analysis of plant productivity data from the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) on NASA's Terra satellite, combined with growing season climate variables, including temperature, solar radiation and water. The plant and climate data are factored into a formula that describes constraints on plant growth at different geographical locations.

For example, growth is generally limited in high latitudes by temperature and in deserts by water. But regional limitations can vary in their degree of impact on growth throughout the growing season.

Zhao and Running's analysis showed that since 2000, high-latitude Northern Hemisphere ecosystems have continued to benefit from warmer temperatures and a longer growing season. But that effect was offset by warming-associated drought that limited growth in the Southern Hemisphere, resulting in a net global loss of land productivity.

"This past decade's net decline in terrestrial productivity illustrates that a complex interplay between temperature, rainfall, cloudiness and carbon dioxide, probably in combination with other factors such as nutrients and land management, will determine future patterns and trends in productivity," said Diane Wickland, of NASA Headquarters in Washington, D.C., and manager of NASA's Terrestrial Ecology research program.

Researchers are keen on maintaining a record of the trends into the future. For one reason, plants act as a carbon dioxide "sink," and shifting plant productivity is linked to shifting levels of the greenhouse gas in the atmosphere. Also, stresses on plant growth could challenge food production.

"The potential that future warming would cause additional declines does not bode well for the ability of the biosphere to support multiple societal demands for agricultural production, fiber needs, and increasingly, biofuel production," Zhao said in a statement.

- Top 10 Surprising Results of Global Warming

- New Map Shows Which of World's Forests Stand Tallest

- Earth in the Balance: 7 Crucial Tipping Points

This article was provided by OurAmazingPlanet, a sister site to LiveScience.