A virus and bacteria may 'team up' to harm babies' brains

Researchers analyzed blood and cerebrospinal fluid from 100 infants in Uganda with hydrocephalus.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

A newly discovered bacteria may be working with a common virus to cause a serious brain condition in infants in Uganda, according to a new study.

This brain disorder, called hydrocephalus, involves an abnormal buildup of fluid in the cavities of the brain and is the most common reason for brain surgery in young children, according to the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS). Every year, about 400,000 new cases of hydrocephalus are diagnosed in children worldwide, and the condition remains a major burden in low- and middle-income countries, according to the study published today (Sept. 30) in the journal Science Translational Medicine.

About half of those hydrocephalus cases happen after a prior infection and are known as "post-infectious hydrocephalus," according to the study. But until now, scientists didn't know what microbes were infecting infants, and identifying those pathogens is key to preventing the condition, according to the authors.

Article continues belowRelated: The 12 deadliest viruses on Earth

For nearly 20 years, a small hospital in Uganda called the CURE Children's hospital has been treating thousands of cases of hydrocephalus in children.

"Hydrocephalus is the most common childhood neurosurgical condition that we see in the population that we serve," one of the lead authors Dr. Edith Mbabazi-Kabachelor, director of research, CURE Children's Hospital of Uganda said in a statement. If left untreated in children younger than 2 years of age, hydrocephalus will increase head size, leading to brain damage; the majority of those children will die, and the others will be left with physical or cognitive disabilities, she added.

So a group of international researchers set out to understand what could be causing this brain condition.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Thirteen years ago, while visiting Uganda and seeing a stream of kids with hydrocephalus after infection I asked the doctors, 'What is the biggest problem you have that you can't solve?'" one of the senior authors Steven J. Schiff, Brush Chair professor of engineering and professor of engineering science and mechanics, neurosurgery and physics at Penn State, said in the statement. "'Why don't you figure out what makes these kids sick?' was the reply."

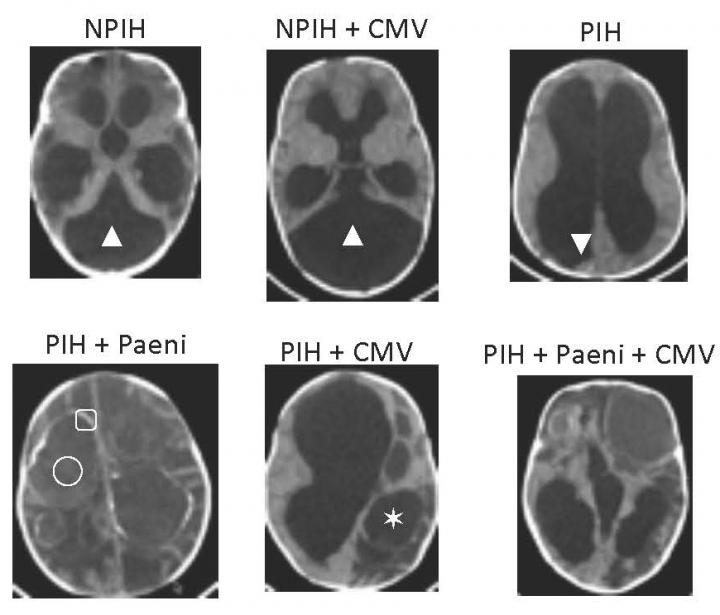

Schiff and his team analyzed blood and cerebrospinal fluid from 100 infants under 3 months old being treated at the CURE Children's hospital for hydrocephalus — 64 of them developed the condition after an infection (doctors knew they had been infected because the babies either had severe illness, seizures or brain imaging showed signs of a prior infection) and 36 without a prior infection (brain images and other tests showed another issue causing the condition such as tumors or cysts).

They sent these samples to two different labs for DNA and RNA sequencing to look for possible traces of genetic material from bacteria, viruses, fungi and parasites. They found that many of the samples from patients with infection-caused hydrocephalus contained "this weird bacteria," Schiff said. The bacteria turned out to be a previously unidentified strain of Paenibacillus thiaminolyticus, now named "Mbale" after the Ugandan city where the CURE hospital is located.

They also found that some of the infants who developed hydrocephalus had also been infected with a common virus called cytomegalovirus (CMV). This virus was found in 18 out of 64 of the available blood samples from babies with post-infectious hydrocephalus and in 9 out of 35 of babies with hydrocephalus not following an infection. CMV was also found in the cerebrospinal fluid samples from 8 of the babies with post-infectious hydrocephalus and none of the babies who hadn't previously had an infection.

This virus is found all over the world, and though it typically causes minor symptoms in adults, it can cause more serious symptoms in babies, such as brain damage, seizures and failure to thrive, according to the National CMV Foundation. Babies can be born with CMV or they can be infected with it early in life.

The origin of the bacterial infection is more mysterious. Though possibly found in soil or in water, more work is needed to understand where the bacteria lives, Schiff said.

However, the researchers found a correlation — not a causation — between these microbes and hydrocephalus. They aren’t sure how the virus and bacteria are linked to each other and whether they worked together to cause the dangerous brain flooding in newborns, or merely happened to be there to witness it.

Originally published on Live Science.

Yasemin is a staff writer at Live Science, covering health, neuroscience and biology. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Science and the San Jose Mercury News. She has a bachelor's degree in biomedical engineering from the University of Connecticut and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus