Weapons carved from human bone come from drowned land bridge between UK and Europe

Of 10 weapons studied, two were made from human bone.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

About 11,000 years ago, Stone Age hunters crafted sharp weapons out of human bone, a new study finds.

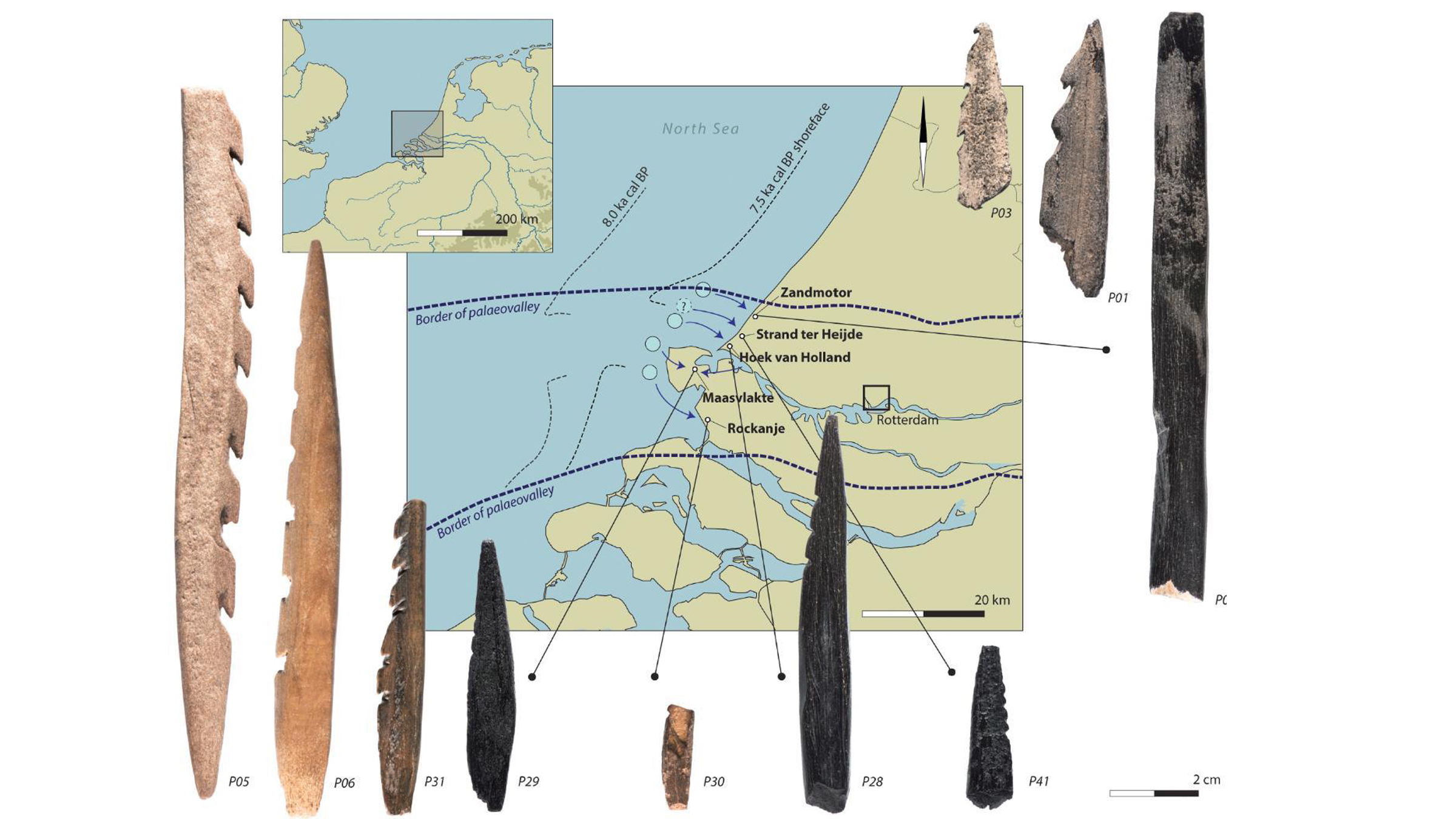

These hunter-gatherers lived in Doggerland, a now-underwater region in the North Sea that connected Europe to Britain. At the end of the last ice age, when sea levels were lower, it was inhabited by herds of animals and humans. Although these people are long gone, artifacts from their culture, including bone weapons, often wash ashore in the Netherlands.

An analysis of 10 of these bone weapons revealed that eight were carved from red deer (Cervus elaphus) bone and antlers, and two were crafted from human bone. "We expected to find some deer, but humans? It wasn't even in my wildest dreams that there would be humans among them," study lead researcher Joannes Dekker, a Master's student of archaeology at Leiden University in the Netherlands, told Live Science.

Related: 25 grisly archaeological discoveries

It's a mystery why these weapons, known as barbed points, were carved from human bone. The research team couldn't think of a practical reason — human bones were likely hard to come by (unlike deer remains) and human bone isn't an especially great material for crafting sharp weapons — deer antler is much better, Dekker said.

Rather, "there were probably cultural rules on what species to use for barbed point production," he said. "We think it was a conscious choice ... [that had to do] with the connotations and associations that people had with those [deceased] people as symbols."

Bone deep

There are nearly 1,000 known bones weapons from Doggerland, named for the nearby Dogger Bank, a shallow area popular in the Middle Ages among Dutch fishing boats, called doggers. Some of these barbed points are small, about 2.5 inches (9 centimeters) long, but others are longer, the researchers said. The barbed points could have been thrown like javelins, launched like arrows from a bow, or thrust from spears, Dekker said. Whatever the method, impact scars and cracks on their tips show they had high-velocity impacts with targets, earlier research found.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

These artifacts have washed ashore in the Netherlands for years, but the number of findings accelerated over the past few decades as the Dutch began dredging the seafloor to help fortify their coastlines, Dekker added.

Radiocarbon dating revealed that these bone weapons dated to between 11,000 and 8,000 years ago, during the Mesolithic, or Middle Stone Age, Dekker and his colleagues found. By analyzing unique collagen proteins in each bone, the team determined the species for each weapon. Finally, by studying variations, or isotopes, of carbon and nitrogen in each of the bones, the team learned that, unsurprisingly, the deer had an herbivorous diet, while the two humans ate animals that lived on land and in freshwater.

Related: Back to the Stone Age: 17 key milestones in Paleolithic life

Dekker noted his study was small, and only larger analyses may reveal how common human bone weapons were in Mesolithic Doggerland. It's also unclear which anatomical bone they came from, but one of the long leg or arm bones would have probably worked best, given the weapons' sizes, he said.

One thing is clear: These bones were carved soon after the person's death, because fresh human bones are much easier to carve than dry, brittle ones, Dekker said.

Although "the use of human bone for bone tools is so rare," it's not without precedent, Dekker said. New Guinea warriors, for instance, used daggers made from human thigh bones, but only from very important people.

The new study is published in the February 2021 issue of the Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports.

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus