Why New Guinea Warriors Prized Human Bone Daggers

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

When facing rivals, the warriors of New Guinea had a choice of deadly bone daggers; they could fight with daggers crafted from human thighbones or weapons shaped from the thighbones of cassowaries, flightless, dinosaur-like birds.

But which type of dagger — the human or the cassowary — is stronger?

According to a new study, the dagger fashioned from human bone is stronger than the giant bird's thighbone, largely because of the way the warriors of New Guinea carved the weapons. [In Photos: The Smoked Mummies of Papua New Guinea]

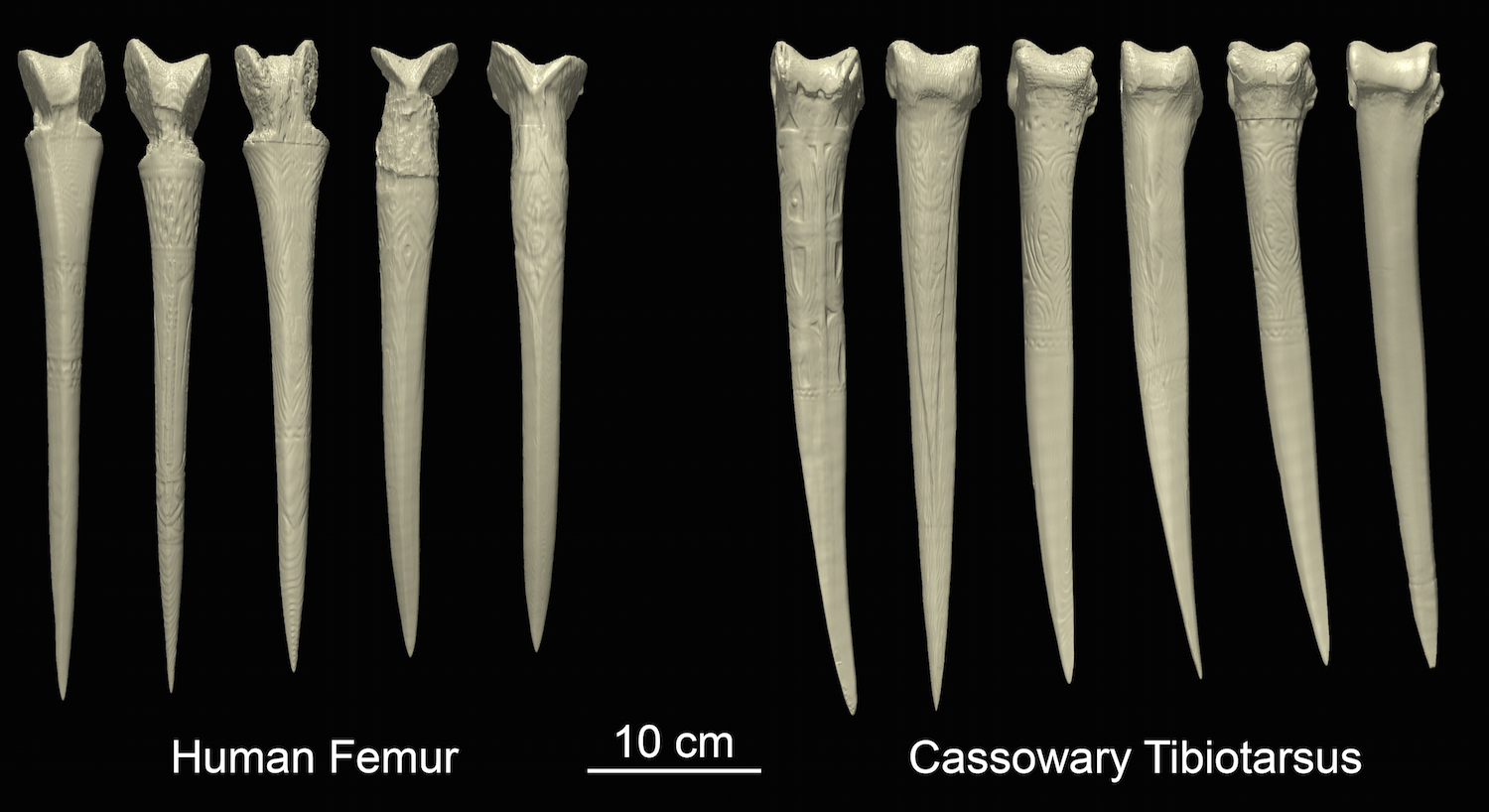

"It looks like both bone types are equally suited for making daggers," study lead researcher Nathaniel Dominy, a professor of anthropology at Dartmouth College in New Hampshire, told Live Science. "The difference is that when men are shaping human daggers, they're retaining a lot of the curvature, which gives it a natural, superior strength."

Because the cassowary bone daggers are whittled to be flatter and less curved than the human variety, they're not as strong as the human daggers, Dominy said.

Dagger quest

This peculiar investigation started when Dominy came across a drawer full of daggers, each roughly 12 inches (30 centimeters) long and made out of cassowary and human thighbones. He found the weapons at the Hood Museum of Art at Dartmouth College. The elaborately carved daggers were stunning, Dominy said. A little investigation revealed that warriors in New Guinea fought with the close-combat weapons "to kill outright or finish off victims wounded with arrows or spears, by stabbing them in the neck," Dominy and his colleagues wrote in the study. Other historical accounts described how the bone daggers were used to disable prisoners who were later cannibalized, Dominy found.

However, the accounts of warriors using the bone daggers for mutilation and cannibalism were written in the late 1800s and early to mid 1900s by outsiders, such as missionaries. Untrained in the ways of modern anthropology, these writers may have exaggerated or misunderstood the cultural practices they encountered, Dominy and his colleagues wrote. So, "the veracity of these accounts is difficult to assess," the researchers wrote in the new study.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Whether used for cannibalism or not, however, these daggers were clearly prized by the people of New Guinea, Dominy said. "Human bone daggers have to be sourced from a really important person," he said. "You can't just take the bone of any ordinary person. It has to be your father or someone who was respected in the community."

That's because the dagger was thought to retain the spiritual strengths, rights and powers of the person from whom the bone came, Dominy said. Basically, whoever wielded the dagger could publicly proclaim to have the rights and powers of the bone's original owner.

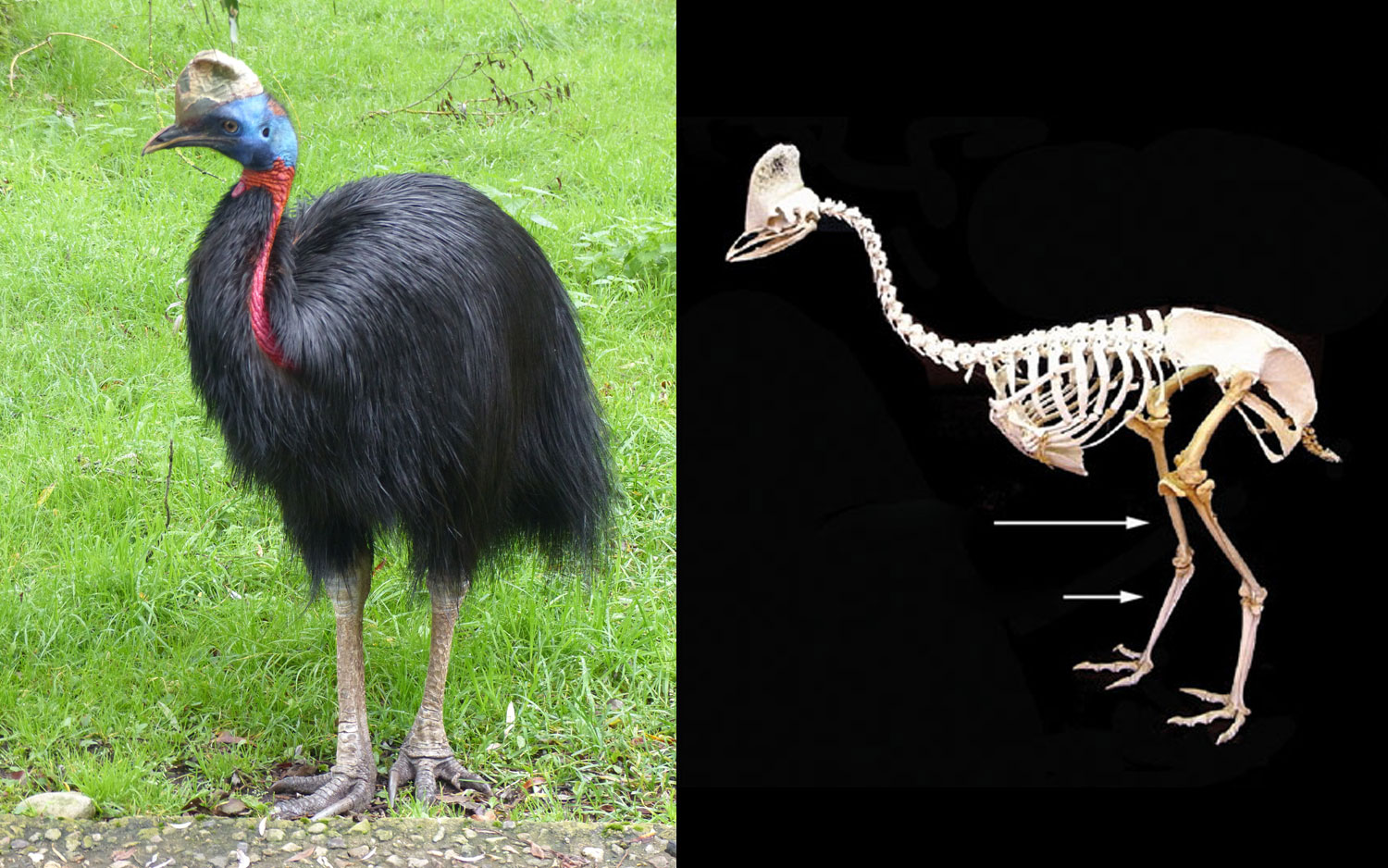

Meanwhile, cassowaries may be frugivores (fruit eaters), but they're one of the world's most dangerous birds. Each of the cassowary's feet has a dagger-like claw that measures up to 4.7 inches (12 cm) long and can slice open any predator with a swift kick, the researchers said. The bird can run up to 31 mph (50 km/h), jump nearly 5 feet (1.5 meters) into the air and swim like a champ, according to the San Diego Zoo.

Bony strength

Traditional cassowary and human bone daggers in New Guinea are rare today, but modern cassowary-bone weapons are still carved and sold for high prices, Dominy said. To see which dagger type was stronger, the researchers performed computed tomography (CT) scans of five cassowary daggers and five human-bone daggers. Using these scans, the researchers could assess the density of each dagger, Dominy said. (Go here to see one of the scanned daggers. If you click on the bone, it will take you a site where you can rotate the object in 3D.)

The researchers bought an additional cassowary-bone dagger for the study and sacrificed it in a bending test to see how much force it could take before breaking. They found that it could handle up to 44 lbs. (200 newtons) of force before it snapped. In all, the research showed that human daggers are about twice as strong as cassowary daggers, study co-researcher R. Dana Carpenter, an assistant professor in the Department of Mechanical Engineering at the University of Colorado Denver, told Live Science.

Given that cassowary daggers are easier to replace than human-bone daggers, it makes sense that the human daggers were carved with greater care to make them stronger, the researchers said. This added strength would lend the dagger a longer shelf life, giving the warrior more time to signal the possession of symbolic strength and prestige, Dominy said.

The study will be published online Wednesday (April 25) in the journal Royal Society Open Science.

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus