Auroras headed to the US again in aftermath of gargantuan 'X-class' solar flare

Auroras may once again be visible in northern parts of the U.S. this weekend as Earth braces for impact from a powerful coronal mass ejection.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Aurora chasers may be in for a treat once again this weekend as an enormous blob of charged particles barrels toward our planet in the wake of a colossal X-class solar flare.

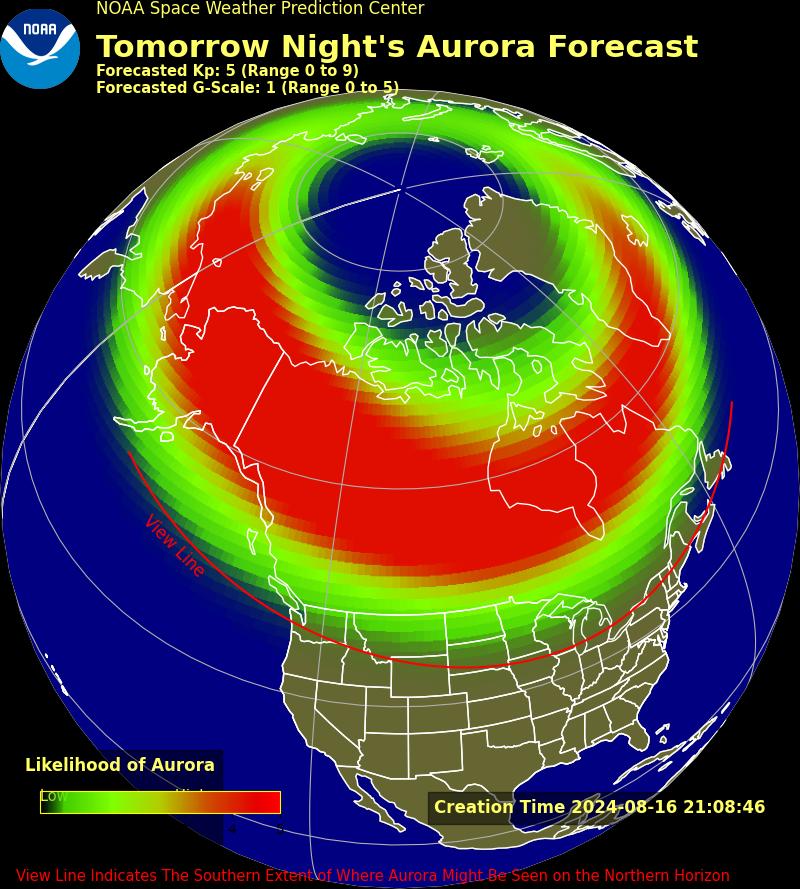

The packet of particles, called a coronal mass ejection (CME), looks poised to hit Earth sometime between Saturday night (Aug. 17) and early Sunday morning (Aug. 18), according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's (NOAA) Space Weather Prediction Center.

This collision will trigger a minor to moderate geomagnetic storm — a disturbance in Earth's magnetic field — that could briefly disrupt certain satellite operations, trigger radio blackouts, and push the northern lights to lower latitudes than usual.

NOAA isn't certain when the CME will strike or how strong it will be, but the agency predicts that auroras may become visible in the states along the U.S.-Canada border beginning Saturday night. Auroral activity may increase going into Sunday, depending on the strength of the incoming solar eruption.

The CME currently headed our way launched from the sun on Aug. 14, following the eruption of a gargantuan X-class solar flare — the most powerful class of solar outburst. Flares occur when tangled magnetic-field lines in the sun's atmosphere suddenly snap and reconnect, shooting powerful blasts of electromagnetic radiation into space. Powerful flares may be accompanied by CMEs, which ooze through space more slowly than flares and usually reach Earth several days after the solar outbursts.

Related: 32 stunning photos of auroras seen from space

Earth's magnetic field mostly protects us from the barrage of charged particles that make up CMEs (with some major exceptions, like the infamous Carrington Event of 1859). As those particles skate along our planet's magnetic-field lines, they charge up and excite molecules in the atmosphere, causing them to emit energy as colorful light — better known as auroras.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Solar flares, CMEs and auroras are more common during solar maximum, the peak of the sun's 11-year activity cycle. Scientists initially predicted that the current cycle's peak would begin in 2025, but there are signs that it may already be upon us. Even if this weekend's auroral display eludes you, expect more chances to view the northern lights in the months to come.

To view auroras, head as far from artificial light sources as possible, using a dark-sky map if necessary. Auroras are visible with the naked eye, but a smartphone camera should be able to capture the atmospheric light show with even greater sensitivity. A good astrophotography camera can also work wonders.

Brandon is the space / physics editor at Live Science. With more than 20 years of editorial experience, his writing has appeared in The Washington Post, Reader's Digest, CBS.com, the Richard Dawkins Foundation website and other outlets. He holds a bachelor's degree in creative writing from the University of Arizona, with minors in journalism and media arts. His interests include black holes, asteroids and comets, and the search for extraterrestrial life.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus