Have all 8 planets ever aligned?

The solar system's eight planets will never truly be in a straight line, but they can get close to it.

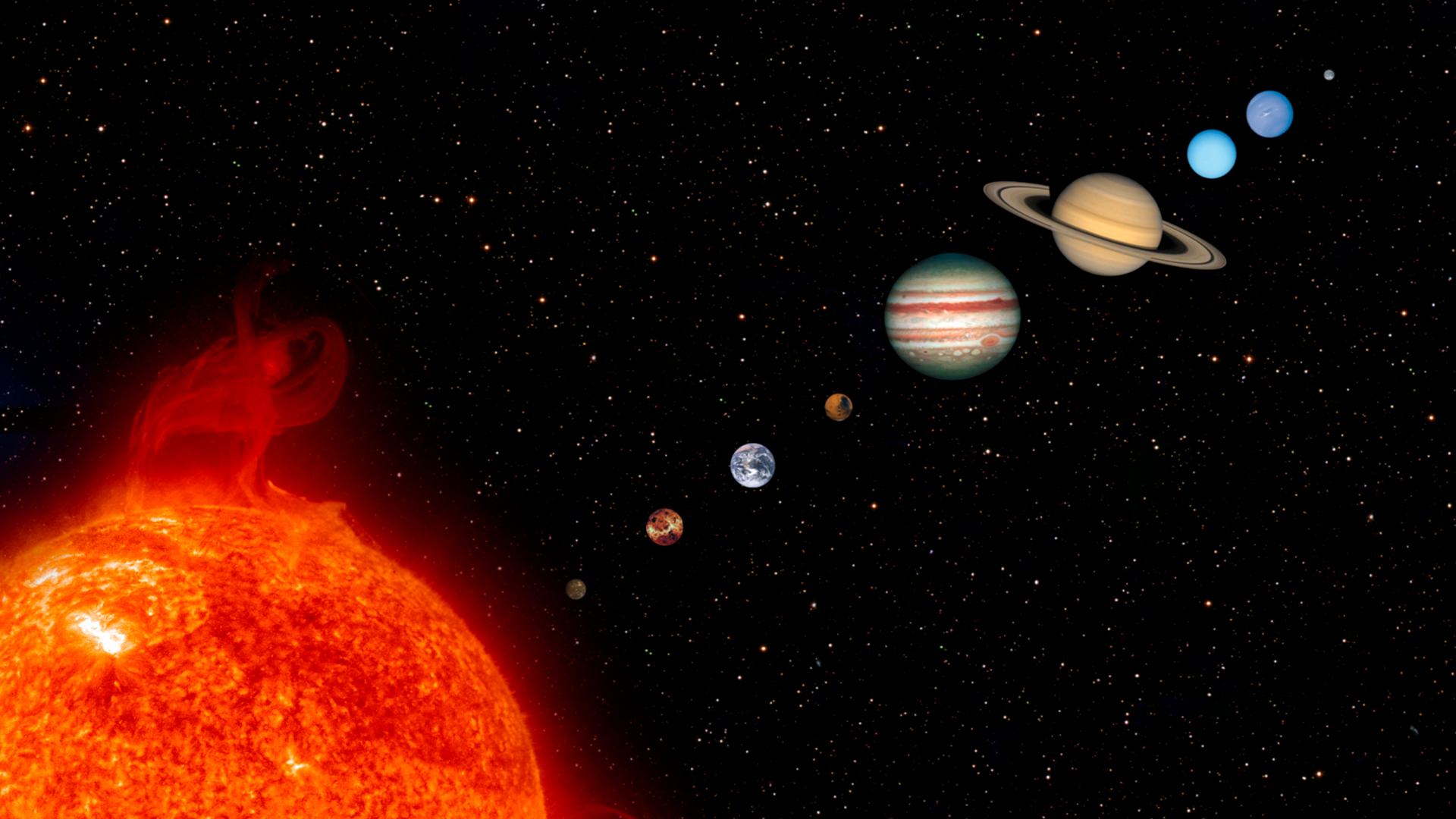

As the solar system's planets rove around the sun, sometimes a few will appear to line up in the sky. But have all eight planets ever truly aligned?

The answer depends on how generous you are with the definition of "align" for the solar system's planets: Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune.

To start with, the orbits of the planets are all tilted to different degrees with respect to the sun's equator. This means that, when planets appear to line up in the sky, in reality they are likely not positioned in a straight line in 3D space, Arthur Kosowsky, an astrophysicist at the University of Pittsburgh, told Live Science.

"The concept of planetary alignment is more about the visual appearance from our perspective on Earth rather than any significant physical alignment in space," Nikhita Madhanpall, an astrophysicist at Wits University in South Africa, told Live Science.

A planetary conjunction is when two or more planets appear close together from our perspective on Earth. It's important to note that the planets are never actually close together. Even when two planets appear lined up to a person on Earth, they are still extremely far apart in space, The Planetary Society notes.

Related: Which planet is closest to Earth? (Hint: There's more than 1 right answer.)

The definition of how close the planets can appear to be considered aligned is not well defined, Wayne Barkhouse, an astrophysicist at the University of North Dakota, told Live Science. Any such definition would involve "angular degrees," the way astronomers measure the apparent distance between two celestial objects in the sky.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

If you measured the distance around the circle of the entire horizon, that would equal 360 degrees. To give an idea of the horizon's enormity, the full moon appears only half a degree across, according to Las Cumbres Observatory in Goleta, California.

In the book "Mathematical Astronomy Morsels" (Willmann-Bell, 1997), Jean Meeus, a Belgian meteorologist and amateur astronomer, calculated that the three innermost planets — Mercury, Venus and Earth — "line up within 3.6 degrees on average every 39.6 years," Barkhouse said.

Lining up more planets takes time. According to Meeus, "all eight planets will line up within 3.6 degrees, for example, every 396 billion years," Barkhouse said. "Which means it has never occurred and will not occur, since the sun will transform into a white dwarf in roughly 6 billion years from now. During this process, the sun will become a red giant and expand in size to swallow both Mercury and Venus, and probably the Earth as well. Thus, only five planets will remain in our solar system."

The chances are worse for all eight planets aligning within 1 degree of sky. According to Meeus, "this will occur, on average, every 13.4 trillion years," Barkhouse said. In comparison, the universe is about 13.8 billion years old.

If you consider the eight planets aligned if they are in the same 180-degree-wide patch of sky, the next time that will happen is May 6, 2492, according to Christopher Baird, an associate professor of physics at West Texas A&M University. The last time the eight planets were grouped within 30 degrees was Jan. 1, 1665, and the next time will be March 20, 2673, according to the National Solar Observatory's facility at Sacramento Peak, California.

Madhanpall noted that planetary alignments have virtually no significant physical effects on Earth. "The only impact to life on Earth during an alignment is the wonderful display visible in the sky," Barkhouse added. "There is no danger of enhanced earthquakes or anything like that. The change in the gravitational force that the Earth will experience due to any planetary alignment is negligible."

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus