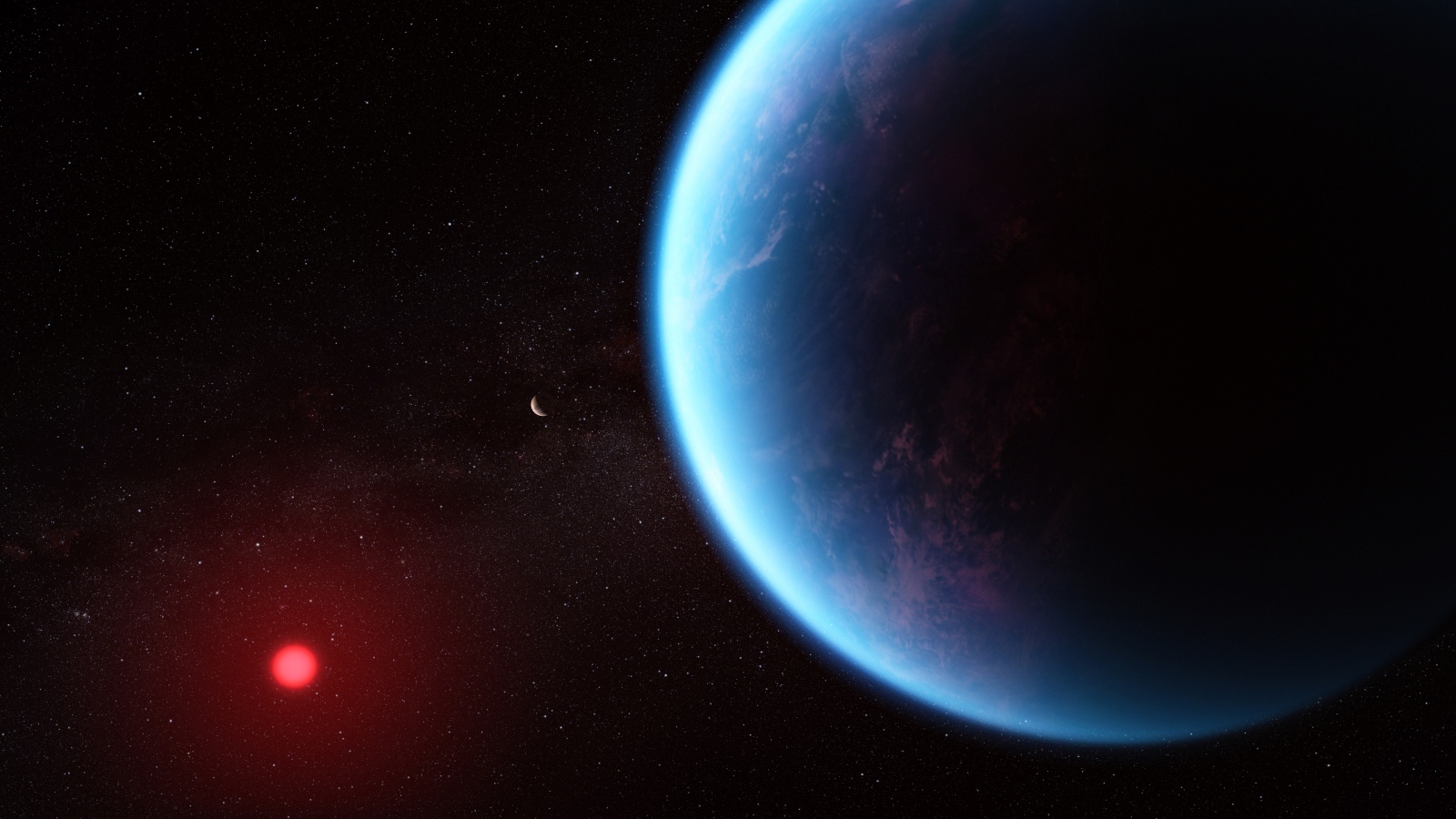

James Webb telescope sees potential signs of alien life in the atmosphere of a distant 'Goldilocks' water world

NASA's James Webb Space Telescope has detected potential traces of dimethyl sulfide, a chemical only known to be created by phytoplankton on Earth, in the atmosphere of an exoplanet believed to have its own liquid ocean.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Earlier this week, Live Science reported that NASA's James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) could likely detect signs of extraterrestrial life on an Earth-like planet up to 50 light-years away. Now, a new study reveals that the state-of-the-art spacecraft may have already spotted one such hint of life — "alien farts" — in the atmosphere of a potentially ocean-covered "Goldilocks" world more than twice as far away.

The exoplanet in question, K2-18 b, is a sub-Neptune planet (between the size of Earth and Neptune) that orbits in the habitable zone around a red dwarf star roughly 120 light-years from the sun. K2-18 b, which is around 8.6 times more massive than our planet and around 2.6 times as wide, was first discovered by NASA's Kepler telescope in 2015. And in 2018, NASA's Hubble telescope discovered water in the exoplanet's atmosphere.

In the new study, which was uploaded to the pre-print server arXiv on Sept. 11 (and will be published in a forthcoming issue of The Astrophysical Journal Letters), researchers used JWST to further analyze light that had passed through K2-18 b's atmosphere.

Related: 10 extreme exoplanets that are out of this world

The resulting atmospheric spectrum, which is the most detailed of its kind ever to be captured from a habitable sub-Neptune planet, shows that the exoplanet's atmosphere contains large amounts of hydrogen, methane and carbon dioxide, and low levels of ammonia. Those chemical markers suggest that K2-18 b could be a hycean world — an exoplanet with a hydrogen-rich atmosphere and a water ocean covering an icy mantle.

Hycean worlds are a prime candidate to harbor extraterrestrial life. However, even if K2-18 b does have an ocean, there is no guarantee that it would be suitable for life: It may be too hot to support life or lack the required nutrients and chemicals to spark life.

Researchers also detected what they believe are traces of dimethyl sulfide (DMS), a foul-smelling chemical that is only known to be produced by microscopic life in Earth's oceans.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

DMS is primarily emitted by phytoplankton, or photosynthetic algae, in Earth's oceans. It is made from sulfur, carbon and hydrogen and is the most abundant organic form of sulfur in Earth's atmosphere, which makes it one of the key biosignatures, or signs of biological life, on our planet.

However, the evidence of DMS "requires further validation," researchers wrote in a statement. It is also possible that some unknown geological process could produce the chemical instead of biological life, they added.

Related: Humans will never live on an exoplanet, Nobel Laureate says

Regardless of whether or not K2-18 b does harbor alien lifeforms, the results of the new study further highlight that Hycean worlds may be ideal places to look for extraterrestrial life.

"Traditionally, the search for life on exoplanets has focused primarily on smaller rocky planets, but the larger Hycean worlds are significantly more conducive to atmospheric observations," study lead author Nikku Madhusudhan, an astrophysicist and exoplanetary scientist at the University of Cambridge in England, said in the statement.

It is unclear how many Hycean worlds there are but "sub-Neptunes are the most common type of planet known so far in the galaxy," study co-author Subhajit Sarkar, an astrophysicist at Cardiff University in Wales, said in the statement.

The study also highlights the incredible power of JWST compared to predecessors like Hubble and Kepler, the researchers added.

"This result was only possible because of the extended wavelength range and unprecedented sensitivity of JWST," Madhusudhan said. The Hubble telescope would have required at least eight times as many observations of K2-18 b to acquire the same level of detail, he added.

The researchers are planning to use JWST to take another look at K2-18 b in the future to see if the telescope can find any more evidence of extraterrestrial life on the exoplanet. If it does, it "would transform our understanding of our place in the universe," Madhusudhan said.

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus