James Webb telescope spies bejeweled 'Einstein ring' made of warped quasar light

New photos from the James Webb Space Telescope show off the bewitching beauty of the warped quasar RX J1131-1231, which is adorned with four bright spots birthed by mind-bending space-time trickery.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

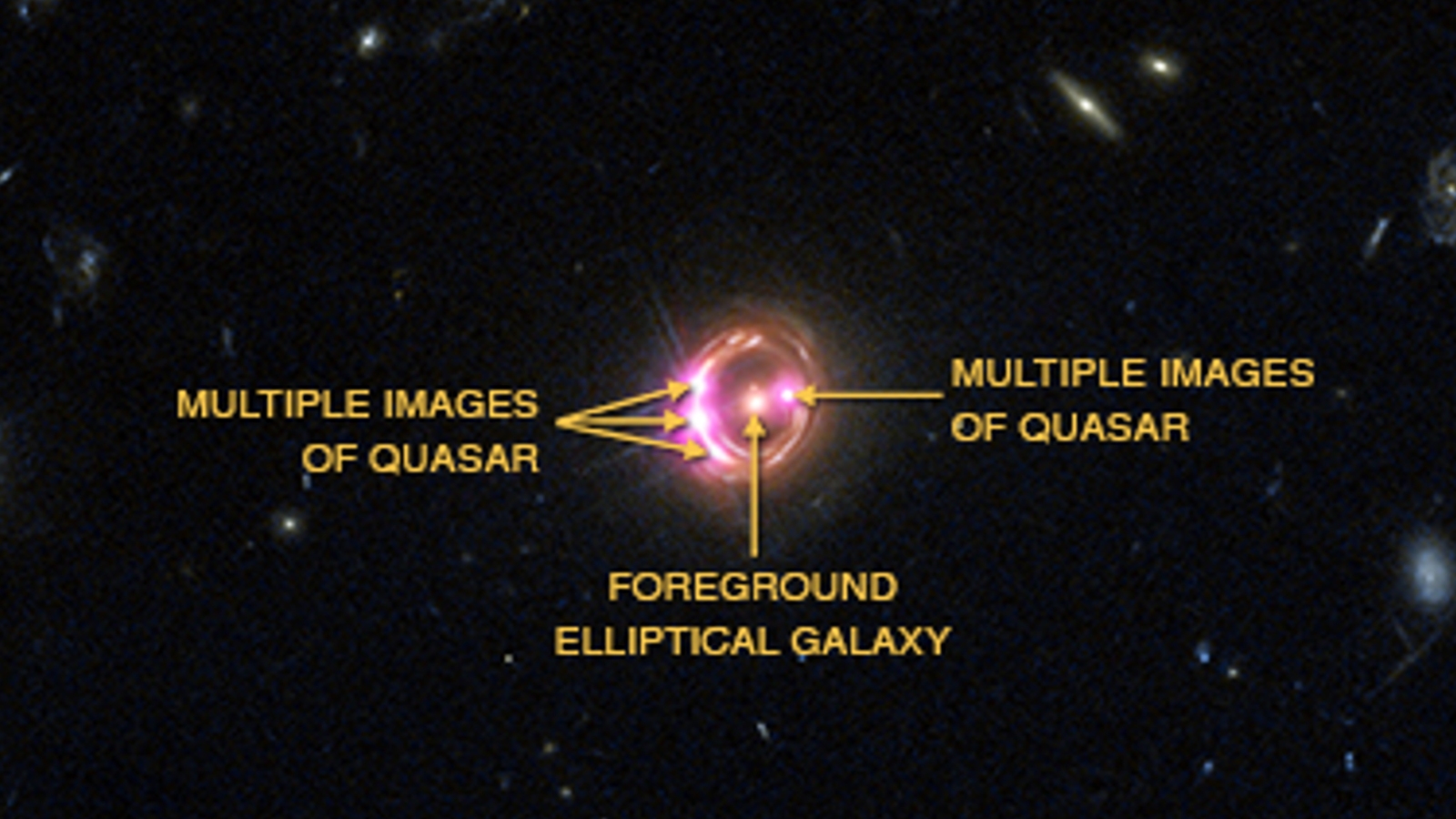

A beautiful, "bejeweled" halo of warped light generated by a monster black hole takes center stage in one of the latest James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) images. The luminous loop, which is strikingly similar to an "Einstein ring," is adorned by four bright spots — but not all of them are real.

The star-studded halo in the new image is made up of light from a quasar — a supermassive black hole at the heart of a young galaxy that shoots out powerful energy jets as it gobbles up enormous amounts of matter. This quasar, previously known to scientists, is named RX J1131-1231 and is located around 6 billion light-years from Earth in the constellation Crater, according to the European Space Agency (ESA).

The quasar's circular shape is the result of a phenomenon known as gravitational lensing, in which the light from a distant object — such as a galaxy, quasar or supernova — travels through space-time that has been curved by the gravity of another massive object located between the distant object and the observer. As a result, light appears to bend around the middle object even though it is traveling in a straight line. In this case, the quasar is being lensed by a closer unnamed galaxy, which is visible as a blue dot in the center of the luminous ring.

Gravitational lensing also magnifies our view of extremely distant objects like RX J1131-1231, which would otherwise be almost invisible to us. This magnification effect can create bright spots in lensed objects, which shine like brilliant gemstones in a piece of jewelry, especially when the distant object is not perfectly aligned with the observer.

This photo has four bright spots, suggesting four different objects are being lensed. However, the orientation and appearance of these jewels around the ring tell us that they are mirror images of a single bright spot, which has been duplicated by the lensing effect, according to ESA.

Bright spot duplication is particularly common with warped quasars because these objects are some of the brightest entities in the universe.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

When the light from a distant, gravitationally-lensed object forms a perfect circle, it is known as an Einstein ring, so named because Albert Einstein first predicted the lensing effect with his theory of general relativity in 1915.

However, in this case, the light has not been perfectly lensed and the ring shape is mainly due to the duplication of the quasar's bright spot. Previous images of the warped quasar also show that the light does not create a perfect circle.

Einstein rings and other gravitationally lensed objects can help reveal hidden information about distant objects. For example, in 2014, researchers used the light from RX J1131-1231 to determine how fast its supermassive black hole was spinning, Live Science's sister site Space.com previously reported.

The size and shape of gravitationally lensed objects also allow scientists to calculate the mass of their lensing galaxies, like the blue dot in this image. By comparing this value to the galaxy's emitted light, researchers can calculate how much dark matter — a mysterious type of matter that doesn't react with light but interacts gravitationally with normal matter — lies within these galaxies. As a result, these warped light shows may be our best tool for uncovering dark matter's secret identity.

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus