Creepy images show airway cells teeming with SARS-CoV-2

The images show a close-up view of the novel coronavirus infecting cells that line the human airway.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

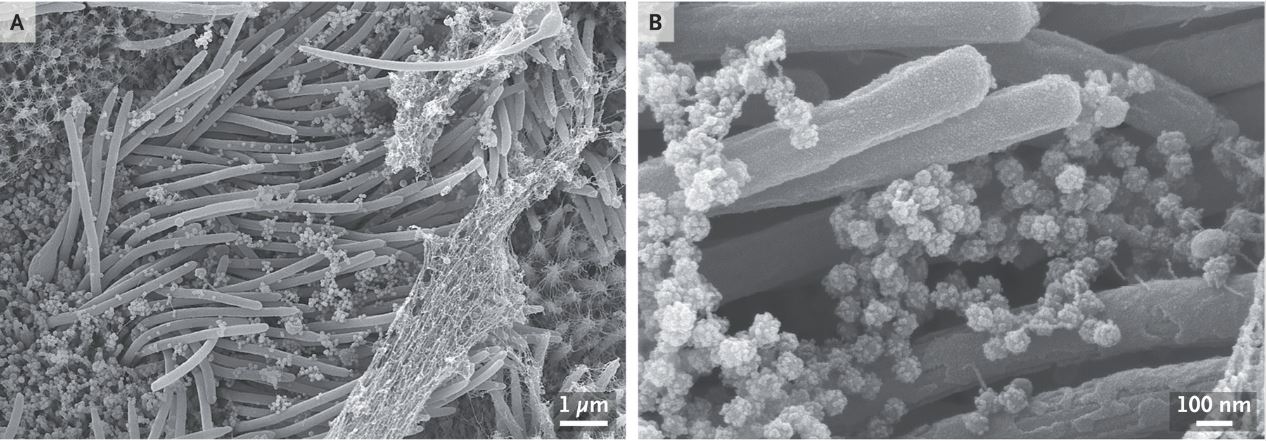

Striking new images show a close-up view of the novel coronavirus as it invades cells that line the human airway. The images provide a glimpse of the staggering number of virus particles that are produced during an infection — indeed, infected cells can churn out virus particles by the thousands.

Camille Ehre, an assistant professor at University of North Carolina School of Medicine's Marsico Lung Institute, captured the images with a scanning electron microscope, a device that uses a focused beam of electrons to produce images. To obtain the images, published Wednesday (Sept. 2) in The New England Journal of Medicine, researchers first infected human airway cells with SARS-CoV-2 — the coronavirus that causes COVID-19 — in lab dishes, and then examined the cells after four days.

The noodle-like projections in the images are cilia, or hair-like structures on the surface of some airway cells. The tips of the cilia are attached to strands of net-like mucus, which is naturally present in the airway.

The SARS-CoV-2 virus particles look like teensy balls. At a high magnification, you can make out the spiky structures on the surfaces of the virus particles. Those crown-like spikes give the family of "coronaviruses" its name. ("Corona" means "crown" in Latin.) The virus uses those spikes to invade human cells.

The image also shows a high density of virus particles, or virions. An analysis of the concentration of virus in the sample suggests a "high number of virions produced and released per [airway] cell," Ehre wrote.

Originally published on Live Science.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus