Roman Republic: The rise and fall of ancient Rome's government

In theory, the Roman Republic was designed to represent both wealthy and poor citizens, but the reality was quite different.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

The Roman Republic was a form of government in Rome that lasted from around 509 B.C. to 27 B.C.

According to ancient Roman writers, the Roman Republic emerged in 509 B.C., after the last king of Rome was deposed. Modern-day historians often consider the official end of the Roman Republic to be 27 B.C., which was the year that Octavian — who had risen to become the ruler of Rome — was given the title "Augustus" (a title that means "revered one") by the Roman senate.

The Roman Republic was a period of territorial expansion presided over by a government that was designed to represent both the wealthy and poor citizens of ancient Rome. While this system somewhat benefited Roman citizens, it often resulted in harsh treatment for anyone who was not a citizen of Rome.

Slow expansion

Surviving historical and archaeological remains indicate that it took centuries for Rome to conquer all of Italy. Progress was very slow with the conquest of even a single city, sometimes taking a century; for instance "the whole fifth century B.C. was taken up with battles against the wealthy and powerful Etruscan city of Veii," wrote Klaus Bringmann, who was a professor of Greek and Roman history at Johann Wolfgang Goethe University in his book "A History of the Roman Republic" (Polity Books, 2007). It wasn't until 396 B.C. that Veii "was conquered and destroyed," wrote Bringmann. Any celebratory attitude in Rome was undone when the Gauls sacked Rome in 390 B.C.

Rome recovered, however, and in the fourth century B.C. the Roman military fought against both a people called the "Samnites" and a group of cities known as the "Latin League," wrote Bringmann, noting that at times Rome was allied with Carthage, a city against which it would later fight a series of wars.

Rome gradually took over cities and territories in Italy, employing a variety of tactics, Bringmann noted. Sometimes Rome built a colony on newly conquered territory. Sometimes a city would join with Rome, its inhabitants granted full or limited Roman citizenship. At other times, a city would agree to form an alliance with Rome and promised to provide troops to Rome when requested. These tactics would gradually see Rome take control of much of the Italian mainland during the fourth and third centuries B.C.

With these tactics, Rome built up a large force of soldiers who were either Roman citizens or citizens of cities allied with Rome. The Greek historian Polybius (ca. 200 B.C. — 118 B.C.) claimed that by 225 B.C. Rome could field a force of over 700,000 soldiers. "None of the great Mediterranean powers with whom Rome fought wars in the third or second centuries B.C. could match figures of this kind," Bringmann said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

This large source of military manpower meant that Rome could readily replace soldiers who had been killed or wounded. This proved important during many conflicts. For instance, between 280 B.C. and 275 B.C., Rome fought a war against King Pyrrhus, who ruled a kingdom called "Epirus" that incorporated parts of modern-day Albania and northern Greece. During this war, Pyrrhus won several military victories during which both sides sustained heavy casualties. However, while the Romans could readily replace their losses, King Pyrrhus could not and ultimately his forces were whittled down and defeated during the war. The term "Pyrrhic victory" is used today to describe a victory that takes a heavy toll on the victor, a toll heavy enough that it may prevent them from winning a war.

What was the Roman Republic?

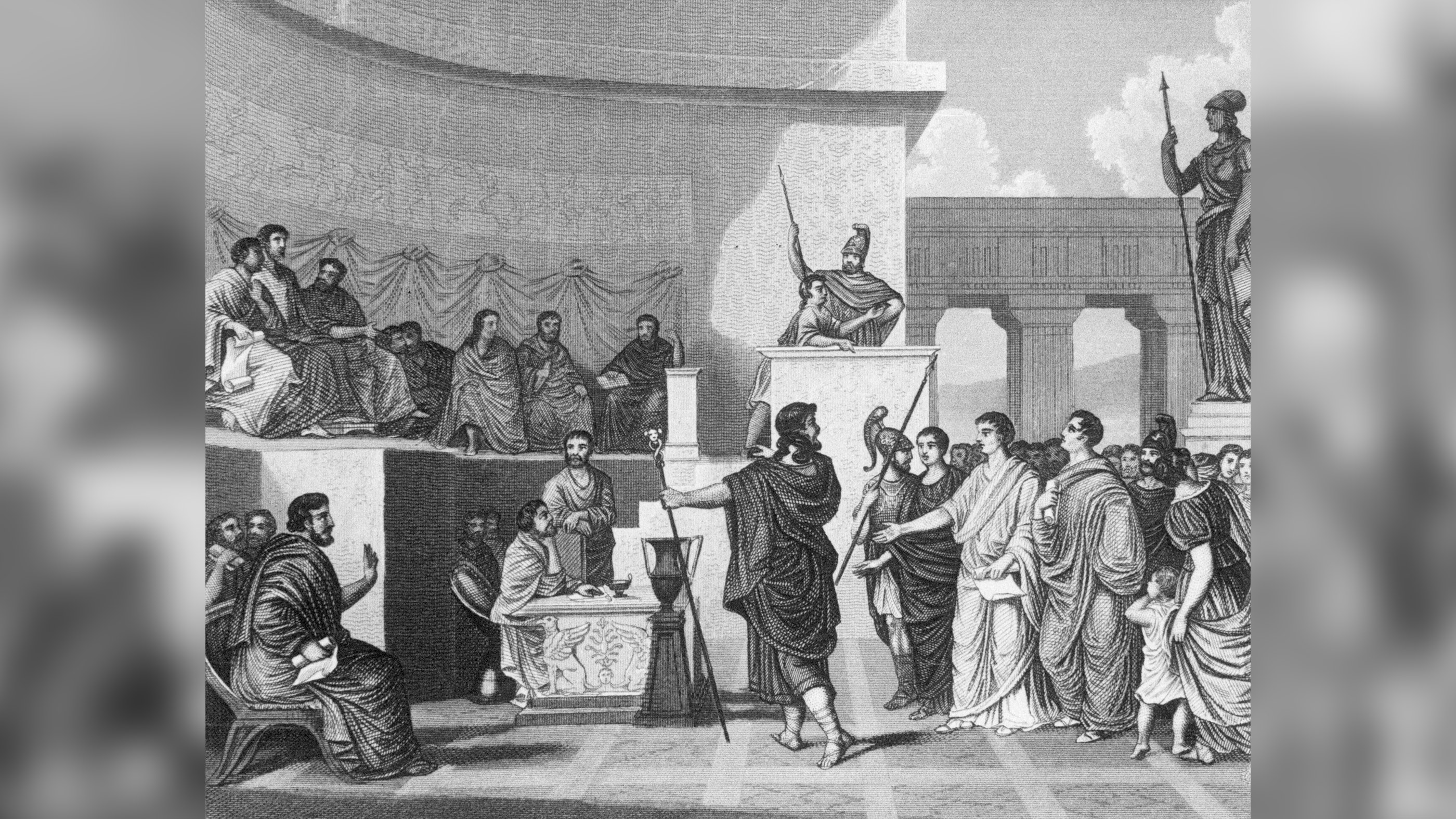

The Roman Republic used a complex system that incorporated a senate, consuls, magistrates, tribunes, and at times a dictator and other public officials. This system changed over time, incorporating the interests of both the patricians (the families of Rome that were from a noble, elite, background) and the plebeians, Roman citizens who were not nobles and often came from poorer backgrounds.

By 366 B.C., this system consisted of two consuls; a praetor, plebeian tribunes (who could hold a great deal of power); quaesters (who specialized in financial affairs); two aediles (who were in charge of public safety, grain supply, Rome's markets and public religious games); censors (who kept track of Rome's population); a senate; several magistrates; a plebeian assembly (or council); a centuriate assembly and at times a dictator who, with the approval of Rome's senate, could hold absolute power for six months during a military campaign, Bringmann said. By 321 B.C., the republic established a rule that required one consul to be from a patrician background and one from a plebeian background.

For voting purposes, citizens were often divided into a system of centuries and tribes, a person's wealth or geographic location sometimes having a bearing on which century and tribe they belonged to, wrote Bringmann. As time went on, and Roman territory expanded, the republic system broke down and sometimes led to two or more strongmen fighting for control of Rome.

The Punic Wars

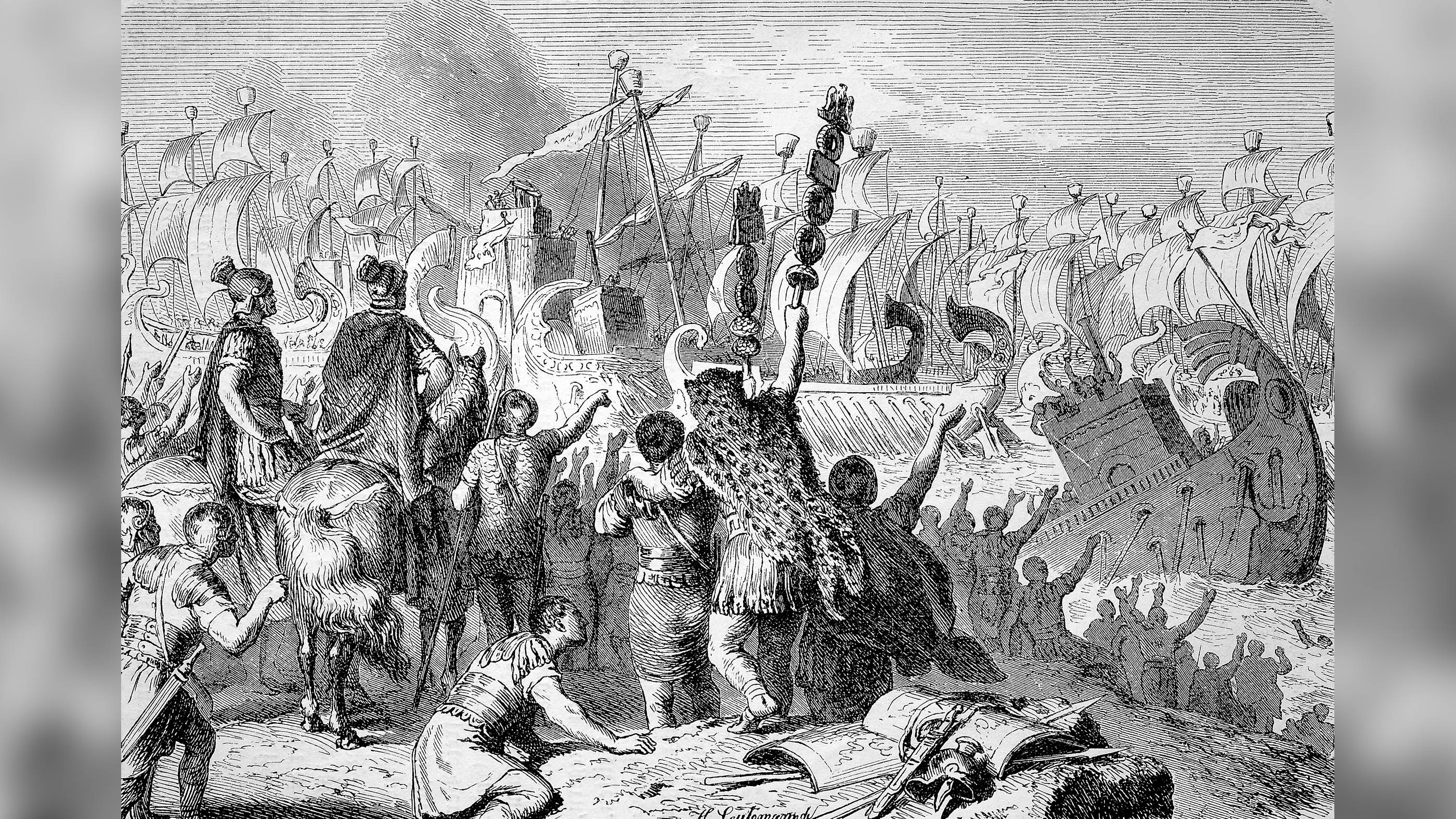

Rome fought three wars against Carthage, a city in North Africa, that ended in Rome gaining control of Sicily, Sardinia, Corsica and parts of Spain and North Africa. The first war, which lasted from 264 B.C. to 241 B.C., saw battles in Sicily, Malta, Lipara, the coast of mainland Italy, North Africa and the Mediterranean Sea, wrote Bringmann, noting that Rome built up its navy during this lengthy war. During the final battle of the first war, Rome gained naval superiority, trapping a Carthaginian force in Sicily. Carthage ceded a sizable amount of territory, including Sicily, to Rome.

The second Punic War occurred from 218 B.C. to 201 B.C., when the Carthaginian general Hannibal led an invasion force overland through the Alps into Italy, allying with the Celts. This force moved south through Italy, capturing several towns but taking sizable losses. Meanwhile, the Romans invaded North Africa, forcing Hannibal to retreat. The Romans succeeded in conquering Carthage, forcing the city to give its remaining territory, and cede its autonomy, to Rome, Bringmann wrote.

During the third Punic War, fought from 149 B.C. to 146 B.C., a Roman force landed in North Africa and destroyed Carthage, wiping out the city. This destruction would lead to a myth that the Romans "salted the earth" after Carthage's destruction to make it harder for anyone living in the area to grow crops where Carthage once stood.

While the myth is not true, and the Romans eventually built a new city where Carthage had stood, the wars left Rome as the most powerful state in the Mediterranean, putting it in a strong position to expand its power eastward into the Balkans, Greece and the Middle East.

Key to Rome's victory was the fact that it had a much larger military force to draw on. Polybius claimed that during the second Punic war the Carthaginian general Hannibal invaded Italy with fewer than 20,000 men, while the Romans could draw on over 700,000 to counter this invasion force.

Bringmann noted that during the Punic Wars, Carthage tried to augment its troops by hiring mercenaries — something that put a financial burden on Carthage as it had to come up with cash to pay a mercenary force.

Rome expanded in the Balkans and Greece between the second and third Punic Wars, gaining territory that it held either direct or indirect control over. The year 146 B.C. proved pivotal, as Rome not only destroyed Carthage but also Corinth, a city in Greece that had opposed Roman expansion into the eastern Mediterranean.

"Rome had now annihilated its richest, oldest and most powerful rivals in the Mediterranean world," wrote Mary Beard, a professor of Classics at the University of Cambridge, in her book "SPQR: A History of Ancient Rome" (Liveright, 2016)

With both Carthage and Corinth destroyed, Rome secured an immense territory that included Sicily, Sardinia, much of Iberia, parts of North Africa and a considerable amount of Greece. It also controlled territory in the Balkans.

Roman governors often controlled the recently conquered territories, sometimes profiting personally from the territory they ruled, wrote Beard, noting that in 149 B.C. a permanent court was set up in Rome so that foreigners could seek redress against Roman governors who had taken property from them.

Private companies who bid on contracts sometimes collected taxes in the newly conquered territories, wrote Beard. The company would try to make a profit by keeping anything over the amount it bid on, providing an incentive for them to mistreat individuals, Beard wrote.

End of the Roman Republic

In the period after 146 B.C., Rome's territory continued to grow, but the city's republic government crumbled. Strongmen such as Sulla, Pompey, Crassus, Julius Caesar, Mark Antony and Octavian vied for control of Rome. Civil wars and violent unrest occurred during this time.

The Roman historian Sallust (lived 85 B.C. to 35 B.C.) believed that the increasing amount of wealth in Rome, generated partly through Rome's conquered territories, helped bring about the rise of these strongmen and the fall of the Roman Republic. "The lust for money first, then for power, grew upon them; these were, I may say, the root of all evils," wrote Sallust (translation by John Carew Rolfe).

"Roman historians regretted the gradual destruction of peaceful politics. Violence was increasingly taken for granted as a political tool. Traditional restraints and conventions broke down, one by one, until swords, clubs and rioting more or less replaced the ballot box," Beard wrote in her book.

In the period after the destruction of Carthage and Corinth, tensions spiked between Rome's poorer and wealthier classes. On three occasions, Roman senators killed tribunes of the people after they pressed for land reform or the distribution of free food to Rome's poor, Beard wrote. In 121 B.C., after a tribune named Gaius Gracchus was killed, those who supported the senators and murdered him went on a killing spree. Roman historical records say that the "bodies of thousands of [Gaius Gracchus'] supporters clogged the river," wrote Beard.

Another problem the republic faced was that many communities in Italy had limited or no citizenship status, leaving them unrepresented in the republic government and more vulnerable to abuse. The "social war," fought between 91 B.C. and 88 B.C. saw a number of communities in Italy rebel against Roman rule.

"It involved fighting throughout much of the peninsula, including at Pompeii where the marks of the battering by Roman artillery in 89 B.C. can be seen even now on the city walls," wrote Beard, noting that in the end Rome offered citizenship to people in Italy who had not taken up arms or who were prepared to lay them down.

Taking advantage of the instability, a Roman consul named Lucius Cornelius Sulla marched on Rome with the forces under his command. Sulla wanted command of a military expedition against Pontus, a kingdom around the Black Sea. He got the command and four years later, after defeating Pontus, he marched on Rome and had himself appointed dictator, Beard wrote.

Sulla then "presided over a reign of terror and the first organized purge of political enemies in Roman history," Beard wrote. "The names of thousands of men, including about a third of all senators, were posted throughout Italy, a generous price on the heads for anyone cruel, greedy or desperate enough to kill them," Beard wrote. Sulla resigned in 79 B.C. and died the following year.

In the wake of Sulla's death Rome found itself fighting wars in Spain, Thrace and, most seriously, in Italy itself where an escaped gladiator named Spartacus built up an army that may have numbered 40,000 people. It was made up of slaves who had escaped their Roman captors and freedmen who decided to join their cause. Spartacus defeated several Roman forces before being defeated himself in 71 B.C.

The strongmen would keep rising up. In 66 B.C., Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus (also called "Pompey") became leader of a Roman army that fought against Pontus, conquering the kingdom. Pompey also campaigned in Judea, conquering Jerusalem in 63 B.C. and returned to Rome in triumph in 60 B.C.

Pompey formed a triumvirate with Julius Caesar (100 B.C. - 44 B.C.) and Marcus Licinius Crassus (115 B.C. — 53 B.C.) that governed Rome and its growing number of territories. Crassus was one of the richest, if not the richest, man in Rome and used his wealth to help build his political power.

Caesar grew his power base by becoming commander of an army that conquered Gaul and campaigned in Britain between 58 B.C. and — 50 B.C. Crassus also tried his hand at being a military leader but was not so successful and was killed in 53 B.C. while campaigning in the Middle East against the Parthians.

After the death of Crassus, tensions grew between Caesar and Pompey and in January 49 B.C. Caesar led his troops across the Rubicon river (the boundary of northern Italy) and marched on Rome. Some historical records say that when Caesar crossed the Rubicon he said words that are sometimes translated as "the die is cast."

Pompey retreated to the east to gather reinforcements and faced Caesar in Greece, suffering a decisive defeat at the Battle of Pharsalus in 48 B.C. Pompey fled to Egypt after this defeat, hoping to gain support from Egyptian pharaoh Ptolemy XIII, the teenage ruler of ancient Egypt; however, the pharaoh decided to kill Pompey and give his head to Caesar. Caesar stayed in Egypt for a time, ordering that Cleopatra VII become co-ruler of Egypt. Ptolemy XIII tried to fight Caesar and Cleopatra, but he was killed in 47 B.C., either by Roman forces or by drowning while attempting to flee Rome’s army.

Cleopatra and Caesar began a romance that resulted in her giving birth to a son, Caesarion. Whether the child was truly Caesar's is a matter of debate among historians.

Though Pompey was dead, there were forces loyal to him and Roman senators (such as Cato the Younger) who refused to accept Caesar's rule; battles against these Pompey loyalists took place in North Africa and Spain. There were also battles against Pontus, the Black Sea kingdom that Pompey had defeated just a few decades earlier. After a successful battle against a force from Pontus, Caesar supposedly uttered words in Latin that are translated as "I came, I saw, I conquered" or "I came, saw and conquered." But no matter how much conquering Caesar did, there were still many in Rome who opposed the idea of one man having so much power.

In 44 B.C., the Roman senate named Caesar "dictator for life." While Caesar had enough support from the senate to get the measure passed, many senators, led by Brutus and Cassius, were opposed to giving Caesar the title. On March 15 of that year, the Ides of March, a group of senators stabbed Caesar to death inside the senate.

In the wake of Caesar's death, three major factions amassed power in Rome. One was led by Octavian, Caesar's great-nephew, who in Caesar's will was named as his adopted son and heir. The other was led by Mark Antony, one of Caesar's generals, while the other faction was led by Brutus and Cassius.

Forces loyal to Octavian and Antony battled against each other in northern Italy and Gaul for a brief period, before the two men decided to form an alliance against Brutus and Cassius. The combined forces of Octavian and Antony marched east, facing off against Brutus and Cassius' force in Greece, decisively defeating the two in 42 B.C. at the Battle of Philippi.

Octavian and Antony settled into an uneasy truce forming a triumvirate with a politician named Marcus Aemilius Lepidus. Antony married Octavian's sister Octavia however it was an unhappy marriage with Anthony forming a romance with Cleopatra VII that led to Antony and Cleopatra having three children together.

The truce broke down within a decade with the two finding themselves in a conflict that would pit Octavian, who controlled troops based in the western half of the Roman Republic, against the combined forces of Antony and Cleopatra, who together controlled both Egypt's troops and Rome's forces in the Middle East. In September of 31 B.C., Octavian's forces destroyed Antony and Cleopatra's naval forces at the Battle of Actium. Octavian's forces were able to land in Egypt and, after some fighting, were able to capture Alexandria.

Both Antony and Cleopatra died by suicide in 30 B.C., not wishing to be held captive by Octavian's forces. Octavian's forces then took control of Egypt, turning it into a Roman province.

After decades of nearly constant civil war, Octavian became the last strongman standing. In 27 B.C., the senate gave him the name "Augustus," a title that can be translated as "revered one," wrote Beard. Modern-day historians sometimes consider 27 B.C. to be the year that the Roman Republic fully came to an end.

The decision by some modern day historians to mark 27 B.C. as the start of the Roman Empire is somewhat arbitrary. While the title “Augustus” cemented Octavian’s position as sole ruler, he had, for all practical purposes, assumed full control in 30 B.C. after the death of Antony and Cleopatra VII.

Additional resources

- Kids can learn more about ancient Rome and the Roman Republic with this book published by Dinobibi.

- For adults, Klaus Bringmann wrote an in-depth book about the history of the Roman Republic.

- Check out this Smithsonian Magazine article, "Lessons in the Decline of Democracy From the Ruined Roman Republic."

Owen Jarus is a regular contributor to Live Science who writes about archaeology and humans' past. He has also written for The Independent (UK), The Canadian Press (CP) and The Associated Press (AP), among others. Owen has a bachelor of arts degree from the University of Toronto and a journalism degree from Ryerson University.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus