US may turn to more 'pooled testing' as COVID-19 spreads

To better track the spread of COVID-19, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) may approve broader use of "pooled testing," wherein diagnostic tests can be processed in batches rather than one at a time.

With this strategy, samples from five to 10 individuals could be tested once as a single "pooled" sample, Dr. Brett Giroir, deputy secretary of Health and Human Services, said in a press briefing on June 23, The New York Times reported. The FDA has outlined steps for test developers to design and seek approval for such protocols, according to a statement published June 16.

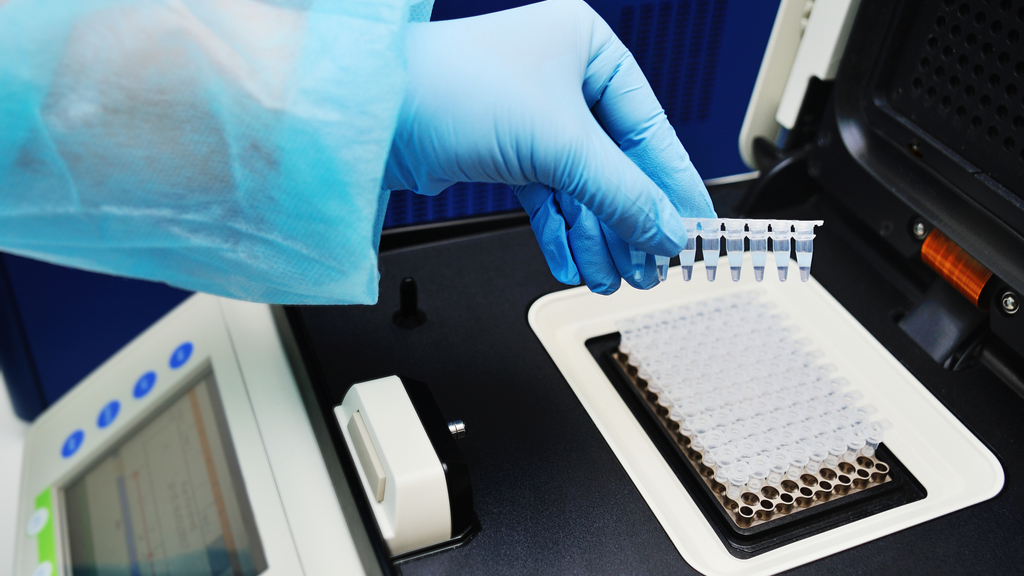

Pooled testing involves taking the nasal or throat swabs from several people and placing those samples into one tube to test for SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. If that pooled sample comes back positive, samples included in the pool must then be retested one by one, to pinpoint the infected individuals. In theory, those infected should then isolate themselves from the broader community and their close contacts can be warned of possible transmission.

But if the pooled sample comes back negative, no additional testing is needed for that group of individuals. That's why the strategy works only if the prevalence of COVID-19 in a given community remains low, Live Science previously reported.

With just a small proportion of the population infected, most pooled tests would come back negative for the virus and not require further testing. But if new infections surge in the community, and the positive test rate gets too high, too many pooled samples would test positive and require further processing, meaning pooled testing wouldn't lead to a net decrease in total tests required.

Related: 11 (sometimes) deadly diseases that hopped across species

One report, published June 23 in the journal JAMA Network, suggests that pooled testing for COVID-19 could work as long as the positive test rate remains below 30%, meaning fewer than 30% of tests come back positive, according to The New York Times. That said, labs already using pooled testing have set that threshold much lower.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

For example, the Nebraska Public Health Laboratory received conditional FDA approval in March to conduct pooled testing, provided that the positive test rate remained below 10% and the pooled samples contained no more than five swabs each, Scientific American reported. Statisticians Chris Bilder and Brianna Hitt helped the lab design their protocol and provided an easy-to-use app to calculate the maximum number of swabs that could be pooled together given those parameters, Live Science reported.

"The lower the prevalence, the higher the pool size that you can use," meaning more swabs can be included in each pooled test, Bilder told Live Science in May.

But the pool size cannot grow indefinitely; other factors set a ceiling on the number of swabs that can be included. If the pool includes too many swabs, regardless of the disease prevalence, positive samples within the batch can become too diluted to detect.

Most COVID-19 diagnostic tests use polymerase chain reaction (PCR), which amplifies the viral RNA manyfold so there's enough to be detected. But PCR machines can process only a finite amount of fluid at one time. As the pool size grows, therefore, each swab included in the pool makes up a smaller proportion of the overall sample. A positive swab will only contain a certain number of viral particles, and if the pool size becomes too great, the chance of the PCR machine detecting those finite particles decreases.

Even when used individually, COVID-19 diagnostic tests can fail to detect viral particles and provide false-negative results; in April, some clinicians estimated that the false-negative rate could be as high as 30%, Live Science previously reported. Selecting the right pool size helps minimize the risk of generating false-negative results during pooled testing.

In the past, pooled testing has been used to screen for syphilis, HIV, chlamydia and malaria, and countries such as Germany and Israel have already adapted the method for COVID-19 screening, Scientific American reported. In addition, the city of Wuhan, China, used the technique as part of their campaign to test all 11 million residents for the virus in less than two weeks, The New York Times reported. Ultimately, the city managed to test more than 9 million residents in 10 days, according to The Wall Street Journal.

While the method only works under certain scenarios, as long as test developers acknowledge those limitations, pooled testing offers an effective strategy for spotting outbreaks before they run out of control, Dr. James Zehnder, director of Clinical Pathology at Stanford University School of Medicine, told Live Science in May. In particular, pooled testing could help control viral spread in vulnerable communities, including health care workers, nursing home residents and prison populations, Live Science reported.

- 20 of the worst epidemics and pandemics in history

- 13 Coronavirus myths busted by science

- The 12 deadliest viruses on Earth

Originally published on Live Science.

OFFER: Save 45% on 'How It Works' 'All About Space' and 'All About History'!

For a limited time, you can take out a digital subscription to any of our best-selling science magazines for just $2.38 per month, or 45% off the standard price for the first three months.

Nicoletta Lanese is the health channel editor at Live Science and was previously a news editor and staff writer at the site. She holds a graduate certificate in science communication from UC Santa Cruz and degrees in neuroscience and dance from the University of Florida. Her work has appeared in The Scientist, Science News, the Mercury News, Mongabay and Stanford Medicine Magazine, among other outlets. Based in NYC, she also remains heavily involved in dance and performs in local choreographers' work.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus