10 times humans messed with nature and it backfired

History is peppered with times when our patchy knowledge of natural systems has led to questionable interventions with unintended — and sometimes disastrous — consequences.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Nature is a complex web that humans have barely begun to untangle. And sometimes, when we try, we just wind up making an even bigger tangle.

From causing roofs to collapse to instigating emu wars, here are 10 times humans messed with nature and it backfired.

1. Operation Cat Drop

In response to a malaria outbreak in Borneo in the early 1950s, the World Health Organization (WHO) sprayed the island with a powerful insecticide called DDT. This successfully killed off the mosquitoes that carried the disease, but it also triggered a cascade of catastrophic, unforeseen events.

DDT is an indiscriminate poison that, it turned out, also exterminated parasitic wasps that preyed on thatch-eating caterpillars. Without the wasps to keep them at bay, the caterpillars multiplied and gnawed at people's roofs, eventually causing the structures to suddenly collapse.

Then, the islanders' cats started dying. The insecticide had moved up the food chain, with geckoes eating the poisoned insects and cats feasting on the geckoes. As the cats died out, the number of rats skyrocketed. The rodents spread disease across the island, sparking outbreaks of typhus and plague.

In 1960, the WHO finally launched Operation Cat Drop to stem the wave of problems it had created, which involved parachuting cats into Borneo. While some reports say 14,000 cats were airdropped in the successful operation, others put this number at 23.

2. The Emu War

When Australian veterans returned from fighting in World War I, the government gifted them land in Western Australia for farming. These holdings started out small, but as the Great Depression gripped the country in 1929, the new owners were encouraged to expand wheat production.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In October 1932, farmers who were already in trouble due to falling wheat prices encountered another threat to their livelihoods. Mobs of emus (Dromaius novaehollandiae) — large flightless birds that look similar to ostriches and are indigenous to the outback — suddenly appeared, trampling and chowing down on their crops. Emus migrate southwest after their breeding season in May and June, and the wheat fields likely provided safe habitat, plentiful food and a reliable source of water.

By November, the damage was so severe the minister of defense sent soldiers to wage war against the emus. On the first day of the Emu War, as it became officially known, the army faced a 50-strong flock with a barrage of machine-gun fire that turned out to be largely ineffective. The birds scattered and ran, dodging the bullets. Six days later, with just a dozen feathered casualties, the war was deemed a lost cause, and the soldiers traipsed home. Major Meredith, who led the troops, was quoted in a 1953 newspaper article, saying the emus "can face machine guns with the invulnerability of tanks."

3. Chasing rat tails

When rats began infesting houses and spreading the plague in 1902, French colonialists in Hanoi decided it was time to tackle the city's rodent problem. They sent the inhabitants of what is now the capital of Vietnam into the sewers to hunt the rats down, which yielded significant results — at first.

To spur the eradication effort and encourage entrepreneurialism, French officials created a bounty for each rat killed of 1 piastre (the currency used in French Indochina between 1887 and 1952). People could collect the reward in exchange for every rat tail handed over as proof of elimination. But as the death toll rose to tens of thousands of rats a day, officials noticed a strange increase in tailless rats scurrying around the city.

Despite the growing mounds of tails, there also seemed to be no decline in the number of living rats. Officials realized that people were releasing amputated rats so they could reproduce, expanding the opportunity to make a profit. Health officials also discovered farming operations dedicated to breeding rats in the city's outskirts. The French later scrapped the bounty. Left unchecked, rats carrying the bubonic plague caused an outbreak in 1906, resulting in 263 deaths.

4. Indestructible starfish

The Indo-Pacific is home to threatened coral reef ecosystems, and one of their natural predators can decimate entire reefs in a matter of months. Crown-of-thorns starfish (Acanthaster planci) can reach 31 inches (80 centimeters) in diameter and sport up to 21 arms covered in hundreds of toxic thorns. They satisfy their voracious appetite by inverting their stomach so it hangs out of their mouth, and sucking the tissue off coral skeletons.

Related: Humans are practically defenseless. Why don't wild animals attack us more?

In some places, people attempted to kill the starfish by chopping them into pieces — forgetting that starfish can regenerate body parts, and so inadvertently multiplied their numbers. People also injected the animals with poisonous chemicals and accidentally caused them to spawn, releasing thousands of sperm and eggs into the water. A more efficient method is to remove the starfish from the reef, according to Oceana.

5. A 100-year-old miscalculation

The Colorado River is a critical source of water for more than 40 million people in seven U.S. states. However, it has shrunk dramatically in the last few decades, in part because of climate change and in part due to a 100-year-old miscalculation.

In 1922, Arizona, California, Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico, Utah and Wyoming divided the Colorado River's water supply among themselves. But their estimate of the river's yearly flow was derived from an unusually wet period of time and was never adjusted, meaning the states had assigned themselves higher amounts of water than the river could provide in normal times. Over the course of a century, this political oversight has led to a 20% decline in the flow of the Colorado River and record-low water levels in the Hoover Dam reservoir and Lake Powell — the two largest reservoirs in the country.

6. Cane toad bonanza

Toward the end of the 19th century, Australia's budding sugarcane industry encountered a bump in the road. Native beetles had acquired a taste for the crops that were introduced a century earlier and were causing huge losses by chomping on the roots.

Entomologists heard about the American toad's (Rhinella marina, formerly Bufo marinus) apparent success in curbing cane beetle populations in Puerto Rico. In 1935, after importing a breeding population from Hawaii, scientists let 2,400 toads loose in the Gordonvale area of Queensland. But they had failed to check whether the toads actually eat cane beetles and, according to the National Museum of Australia, did not assess the potential environmental impacts.

Cane beetle populations held steady, and the bugs continued to ravage sugarcane plantations. Meanwhile, the cane toad population exploded and the amphibians spread from Queensland to coastal New South Wales, the Northern Territory and parts of northwestern Australia. Cane toads secrete venom that can kill animals that eat them, which soon triggered declines in native predators — including northern quolls (Dasyurus hallucatus), now listed as endangered — and caused huge damage to ecosystems.

The invasive toads still wreak havoc today, but "there is unlikely to ever be a broadscale method available to control cane toads across Australia," the Australian government said on its website.

7. Underground inferno

In May 1962, a fire started in the small borough of Centralia, Pennsylvania, which reportedly originated as an intentional burning of residential trash in an abandoned mine. As the flames spread, people tried to douse them with water several times over the next few days, but no amount of effort seemed to extinguish the fire. The waste continued burning into August, when the council alerted local coal companies and state mine inspectors of the possibility of a mine fire.

Centralia sits atop a labyrinth of abandoned coal mines, which may have been set ablaze by an unsealed opening in the trash pit. The fires are still burning today. Federal and state governments gave up fighting the flames in the 1980s, opting to relocate inhabitants instead. The smoldering coal seams have baked the town through the ground, bleaching trees white and opening fissures that leak poisonous gases. Little remains of Centralia except a deserted grid of streets and a dozen people who refused to leave. It could be another 250 years before the coal fueling the underground inferno runs out.

8. Electrocuting fish

Asian carp were imported to the U.S. in the 1970s to deal with algal blooms in water treatment plants and aquaculture ponds. But they soon escaped confinement and made their way into rivers and streams — some species can even jump over low dams and overcome barriers in waterways. Having escaped, they became invasive and interfered with fishing activities.

Carp have spread to the Mississippi River and its tributaries and are on the verge of spilling into the Great Lakes, where they could wreak ecological havoc and tank the annual $7 billion fishing industry. As a preventive measure, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers erected an underwater electric barrier in Chicago's waterway system in 2013. The design stuns fish as they swim upstream, and their limp bodies drift back down. While it seems to have kept carp at bay so far, the barrier may not be completely reliable and could let small fish sneak through.

9. Smash sparrows

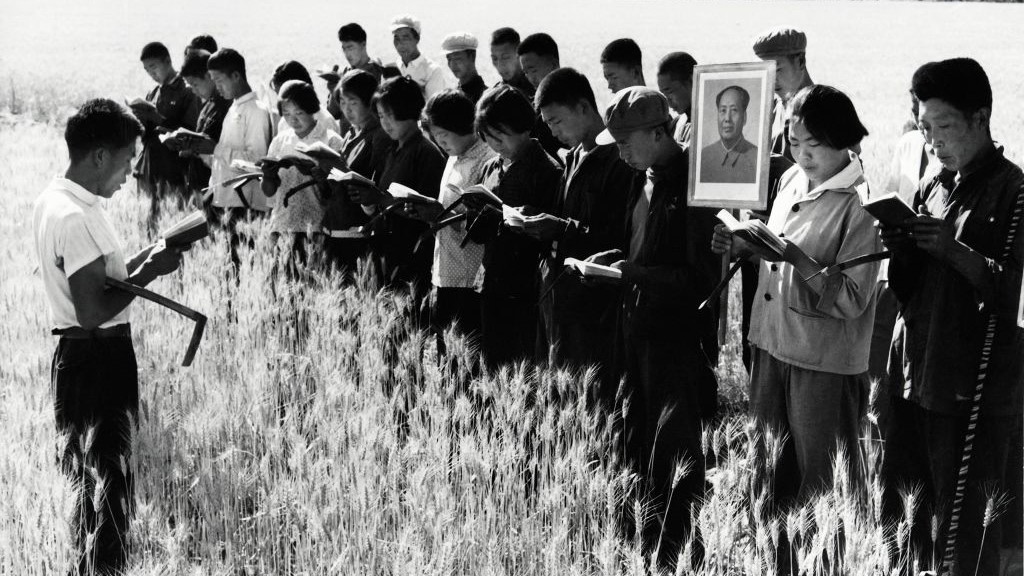

Under the rule of leader Mao Zedong from 1949 to 1976, China underwent an industrial makeover like no other. The slogan "man must conquer nature" became a rallying cry during the Great Leap Forward — a radical social and economic project designed to outproduce Britain and achieve Mao's idea of communism.

Mao launched the "Four Pests" campaign in 1958 and called upon people to eradicate flies, mosquitoes, rats and sparrows. He was convinced sparrows were diminishing crop yields by eating the grain and ordered them to be shot, their nests destroyed and any survivors eliminated by banging pots and pans until they died of exhaustion.

As sparrow numbers dwindled across China, the birds' prey swarmed in. Locusts boomed and crop-eating insects surged. Combined with other effects of Mao's war on nature — including widespread deforestation and pesticide use — and other disastrous policies, the "Smash Sparrow" effort contributed to a devastating famine that killed tens of millions of people.

10. Flushed away

For 7,000 years, the Mississippi River has carried sediment from across North America and deposited it in the Gulf of Mexico. There, the mud piled up into lobes of land separated by swampy water channels, shaping the famous river delta and its marshes. But in 1718, French colonists who founded New Orleans on a finger of land alongside the Mississippi's main channel were dismayed when spring floods sent water streaming through the half-finished buildings. They ordered the construction of a levee — a mound of earth acting as a barrier to keep the city dry. Over the decades, more and more levees were erected until they merged into a wall stretching thousands of miles north into Missouri.

These constructions enabled cities and farmland to flourish, but they also funneled the river into a single torrent. While the Mississippi formerly recycled the soils it flushed away by creating marshland, it now shoots straight out into the gulf and dumps them in the deep sea. As a result, since the 1930s, Louisiana has lost over 2,000 square miles (5,200 square kilometers) of land to the ocean — an area equivalent to a football field drowning every 100 minutes.

The loss of protective wetlands worsens the impact of storms and hurricanes on coastal communities. Compounded by rising sea levels, land loss also threatens Louisiana's commercial fishing industry — which makes up 30% of the U.S. yearly catch — five major ports and rich wetland ecosystems.

Sascha is a U.K.-based staff writer at Live Science. She holds a bachelor’s degree in biology from the University of Southampton in England and a master’s degree in science communication from Imperial College London. Her work has appeared in The Guardian and the health website Zoe. Besides writing, she enjoys playing tennis, bread-making and browsing second-hand shops for hidden gems.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus