The 165-year reign of oil is coming to an end. But will we ever be able to live without it?

Like whale blubber, oil as a dominant source of energy will gradually be phased out over the next decades. Here's what that transition may look like.

Between the 17th and 20th centuries, humans killed millions of whales for oil. They stripped their blubber, spinning the iconic creatures in the water and pulling off the fat in a huge spiral like the peel of an apple. The blubber was boiled into oil, then strained into barrels to be used in everything from oil lamps to industrial lubricants.

This was the bloody process that brought light to society.

"It is horrible," Charles Nordhoff wrote of his experience on a whaling vessel in 1895. "Yet old whalemen delight in it. The fetid smoke is incense to their nostrils. The filthy oil seems to them a glorious representative of prospective dollars and delights."

For over 100 years, the voracious hunger for whale blubber drove blue, humpback and North Atlantic right whales to the brink of extinction.

Now, commercial whaling is all but banned, whale blubber is used in just a handful of products, and whale populations have rebounded somewhat.

A similar sea change is coming for petroleum, though when and how it will play out is still incredibly hazy.

The best superforecasters, combined with machine learning, are only accurate at predicting geopolitical events up to a year in advance, Luke Kemp, research affiliate with the Centre for the Study of Existential Risk and at the University of Cambridge, told Live Science. At best, "we have general pictures we can paint."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But the general trends are clear. We've already transitioned much of our home energy use away from oil. And as climate change pushes us to accelerate that transition, we're developing new technologies that will help the world outgrow its oil dependence ever faster, experts say. In a few industries, like shipping and plastic, the decayed bones of long-dead animals will be the primary energy source for a long time to come.

But a post-oil world is coming.

"The whaling industry is a very good analogy," David MacDonald, a professor of petroleum geology at the University of Aberdeen in the U.K., told Live Science. At its peak, "The whaling industry was huge." But over the decades, "it was an inexorable decline," he said.

Related: How much oil is left and will we ever run out?

Origins of oil

Humans have been using oil for millennia. In fact, around 40,000 years ago, people in what is now Syria used bitumen — a byproduct of crude oil — to stick handles onto their tools. Fast-forward 35,000 years, and the Mesopotamians used the same sticky substance to waterproof their boats. The Babylonians used it to build the Hanging Gardens, and the Egyptians used it to embalm mummies.

In China, people burned crude oil and gas for heat and light as early as 500 B.C. By the fourth century A.D., they were drilling for these natural resources and transporting it via bamboo pipes.

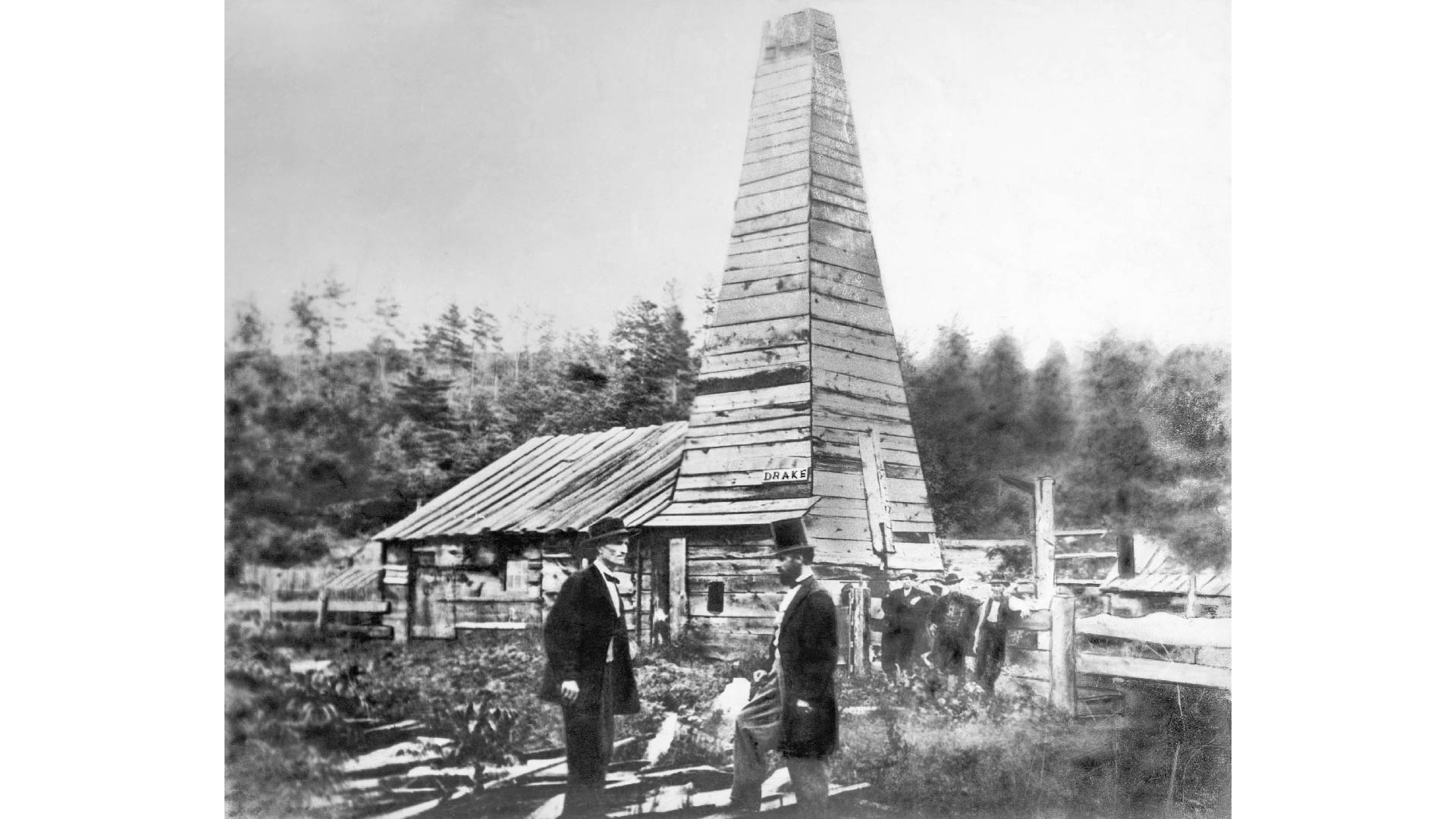

But it wasn't until 1859, when Edwin "Colonel" Drake struck it big in Pennsylvania, that oil was sought at scale. With the same, albeit modernized drilling technique used in China more than 1,500 years earlier, Drake hit a reservoir 69.5 feet (21 meters) down, and the U.S. oil industry was born.

Crude oil, which is composed of simple strings of carbon and hydrogen, forms from the remains of animals and plants that sank to the bottom of swamps, lakes and oceans. Over millions of years, layers of sand and rock covered them, and intense heat and pressure turned these remains into oil and natural gas. They were then locked away in reservoirs — some close to the surface, others thousands of feet below — with gas sitting atop a lake of oil.

For the past 165 years, crude oil has transformed virtually every aspect of society.

If oil vanished tomorrow, global trade would break down as the shipping and aviation industries ground to a halt. Food security would be precarious, with no petroleum to fuel large-scale agriculture or packaging to keep food fresh. Medical care would be set back generations without the sterile equipment needed in hospitals. Renewable energy projects would be frozen without the components required to make solar panels or wind turbines.

Planes, trains, boats and automobiles

Our transition away from oil will be far gentler than that, of course. We've largely stopped using oil for electricity. In October last year, a report by the International Energy Authority found demand for oil will peak this decade.

The rise of electric vehicles (EVs) will usher in the next big drop in oil use.

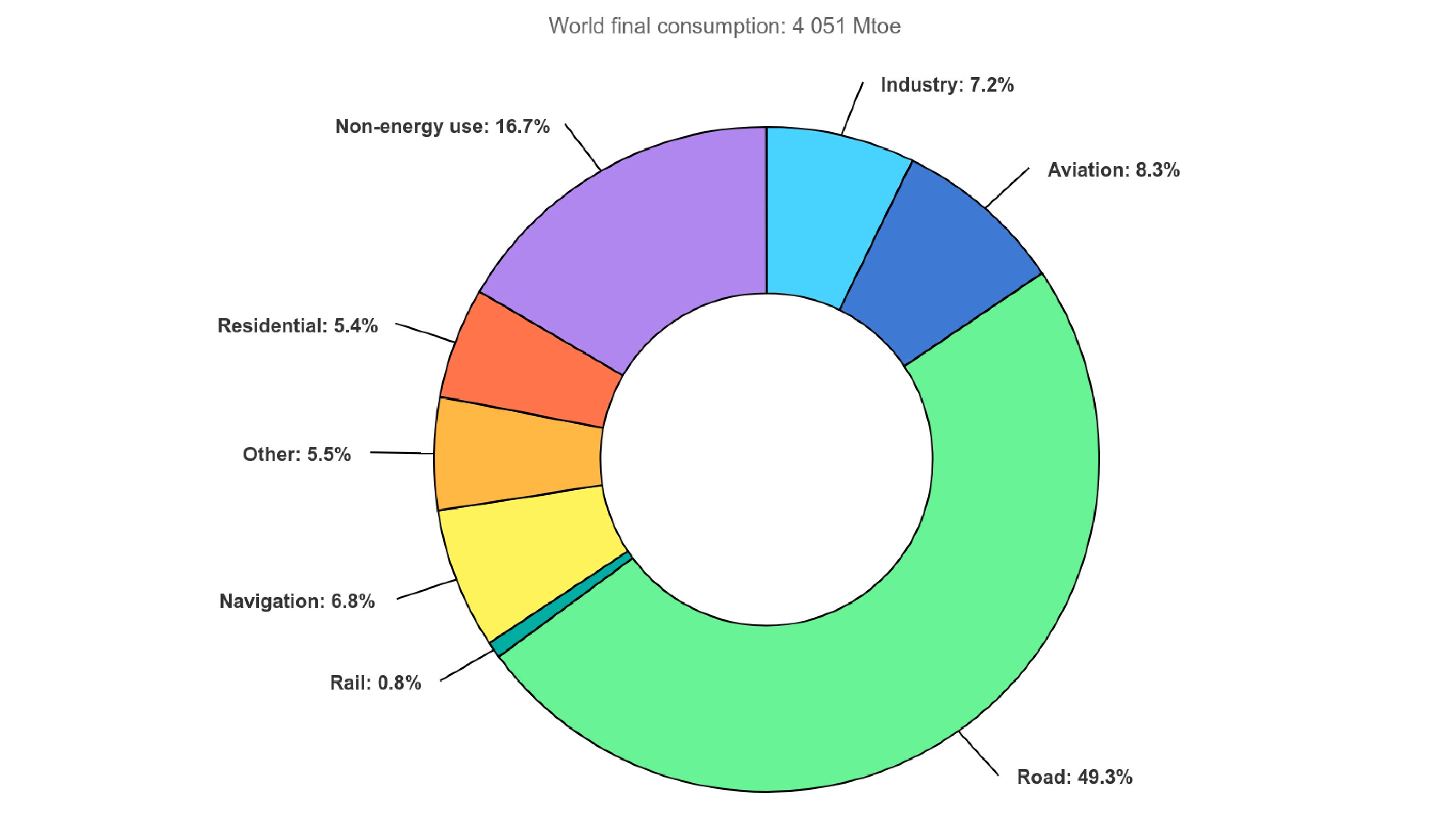

Currently, road vehicles make up almost 50% of global crude oil use, according to a 2018 report by the International Energy Agency (IEA). But this percentage will plummet in the coming decades. It's estimated that EV sales will account for over two-thirds of the global market by 2030. If we are particularly aggressive in slashing fossil fuel emissions by three-quarters by 2050, the EV industry could be responsible "for more than half of the reduction in total oil demand," according to the BP Energy Outlook 2023, which forecasts future fuel use.

In 50 years, most of this car-driven oil usage could be eliminated.

Aviation also largely relies on oil for fuel. Planes last decades and cost tens of millions to hundreds of millions of dollars to build. But technology is moving fast in this sector. New aircraft are far more fuel efficient than aircraft were 40 years ago, and the industry is engaged in reaching net-zero emissions by 2050.

Sustainable aviation fuels (SAFs) will be key to ditching oil. These biofuels are derived from the raw materials used for industrial processes, including waste, biomass, cooking oil and animal fat waste. SAFs have the added benefit of being compatible with current aircraft engines, and they can be blended up to 50% with traditional jet fuel. Boeing plans to make all of its commercial aircraft capable of flying on SAFs by 2030. By 2050, if we aggressively cut carbon emissions, SAFs will account for between 30% and 45% of aviation fuels, BP estimates.

Shipping is a more stubborn problem. Ships run on oil. Like planes, they are wildly expensive to build, last decades and will be hard to phase out. Around 90% of world trade is carried out by the international shipping industry, with over 105,000 merchant ships currently sailing the oceans and accounting for around 5% of oil consumption today.

Without ships transporting goods all over Earth, "half the world would starve and the other half would freeze," according to the International Chamber of Shipping. The problem for this industry is, you can't just change the fuel.

Fredric Bauer, an associate senior lecturer at Lund University in Sweden, researches low-carbon innovation in energy and industrial systems. He's not convinced the shipping industry will be able to transition away from oil anytime soon. The International Maritime Organization published its first climate strategy in 2018 and has generally been "incredibly conservative" in shifting away from fossil fuels, Bauer said.

Hydrogen is a potential alternative fuel. Ships could be retrofitted with hydrogen fuel cells, but that strategy comes with problems. For example, to remain liquid, the fuel must be stored at extremely low temperatures. Its energy density is low, increasing the amount of storage required on each ship. Hydrogen is also extremely explosive.

Hydrogen-powered ships are still in their very early stages. The first ferries and small ships using this technology are being tested, but large, hydrogen-fueled oceanic cargo ships are still in the design phase.

Jay Apt, a professor at Carnegie Mellon University's Tepper School of Business and the Department of Engineering and Public Policy, told Live Science that shipping will likely be a voracious oil user for decades.

"If I was to look into the cloudy crystal ball, I would say that long-haul shipping would be one of the large-scale uses of petroleum that we would see 100 years from now," Apt said.

Related: Solar power generated enough heat to power a steel furnace

Plastic fantastic

Single-use plastics are littering Earth in ever-increasing quantities. They take hundreds of years to degrade and then become microplastics, which are choking the ocean, littering the tops of mountains and congregating inside our bodies.

"The use of plastic is in many ways the more dangerous part of the oil industry, rather than the burning of hydrocarbons," MacDonald said. "If humanity disappeared from Earth tonight, in 1,000 years the levels of CO2 in the atmosphere will be back to normal — whatever normal is — but there would be plastic in the oceans and soils for millions of years."

Synthetic plastic is made from oil, and it is extremely cheap to produce.

Around 12% of the oil extracted today goes toward the petrochemical industry, which makes plastic and fertilizers, along with clothing, medical equipment, detergents and tires. And this number is set to grow: The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development estimates that under current policies, the global use of plastics could triple by 2060.

Related: 10 surprising things that are made from petroleum

Plastic is extremely useful because its density can be varied. We can try to move away from plastic in products like food packaging, but phasing out medical plastic is more challenging. Plastic is everywhere in hospitals, including in disposable syringes, IV bags, catheters, gloves and bed linens. It's not just that plastic is cheap, durable and malleable. It's also sterile, so helps curb the spread of infections.

If humanity disappeared from Earth tonight, in 1,000 years the levels of CO2 in the atmosphere will be back to normal — whatever normal is — but there would be plastic in the oceans and soils for millions of years.

David MacDonald

"I couldn't even imagine health care without plastics, and I don't even think we should go there," Dr. Jodi Sherman, founding director of the Yale Program on Healthcare Environmental Sustainability, told Live Science. "I would argue that plastic has allowed very important innovation of medical devices and supplies, and is here to stay."

Related: Will we ever be able to stop using plastic?

Right now, primary plastics are "ridiculously and unsustainably cheap," so oil-free alternatives can't compete on cost, Bauer said.

Bioplastics, made from crops, could provide a way forward, MacDonald said. But the story of biofuels serves as a cautionary tale. Soybean fields have taken over large swaths of U.S. farmland — in part because of its use as a biofuel.

"We have a finite amount of agricultural land," MacDonald said. "If we turn a lot of it over to growing fuels, what do we do about feeding people? It's not an easy equation. Everything is related and interlinked."

The beginning of the end of oil

"The oil industry isn't going to collapse because we run out of oil, there's plenty of oil left," MacDonald said.

But at some point, clean energy technologies will become so cheap that it won't pay off to drill and extract oil.

The first method to be phased out will be wildcat drilling, in which an area with unproven reserves is explored, MacDonald said. This is risky and extremely costly if you don't find anything. Even drilling new wells in areas with known oil reserves is eye-wateringly expensive: Companies spend tens to hundreds of millions to get wells and rigs staffed up and running, and then it's years before they turn a profit.

"You're spending money like a drunken sailor in the hope you're going to get some money back," MacDonald said. "It ain't a quick process. That's why oil companies are big — they have to be as they're carrying a huge amount of risk."

Still, oil wells will continue to pump in the vast sand fields of Saudi Arabia for decades. In the U.S., production will continue at high levels through 2050.

Femke Nijsse, a complexity scientist at the University of Exeter in the U.K. whose research focuses on modeling climate, energy systems and the economy, told Live Science she's hopeful that global oil use will be cut by 95% by 2065, with aviation and shipping as the remaining strongholds.

MacDonald predicts a "less spectacular" decline, falling a quarter by 2050. "At some point you'll get to a cliff where it will go down quite rapidly," he added.

Some experts can't imagine a post-oil future at all. Kevin Book, managing director of ClearView, a research firm that looks at energy trends, told Live Science that artificial intelligence and geoengineering will change oil extraction and refining, but that oil won't disappear until a technology that doesn't exist yet, like fusion energy, makes it obsolete.

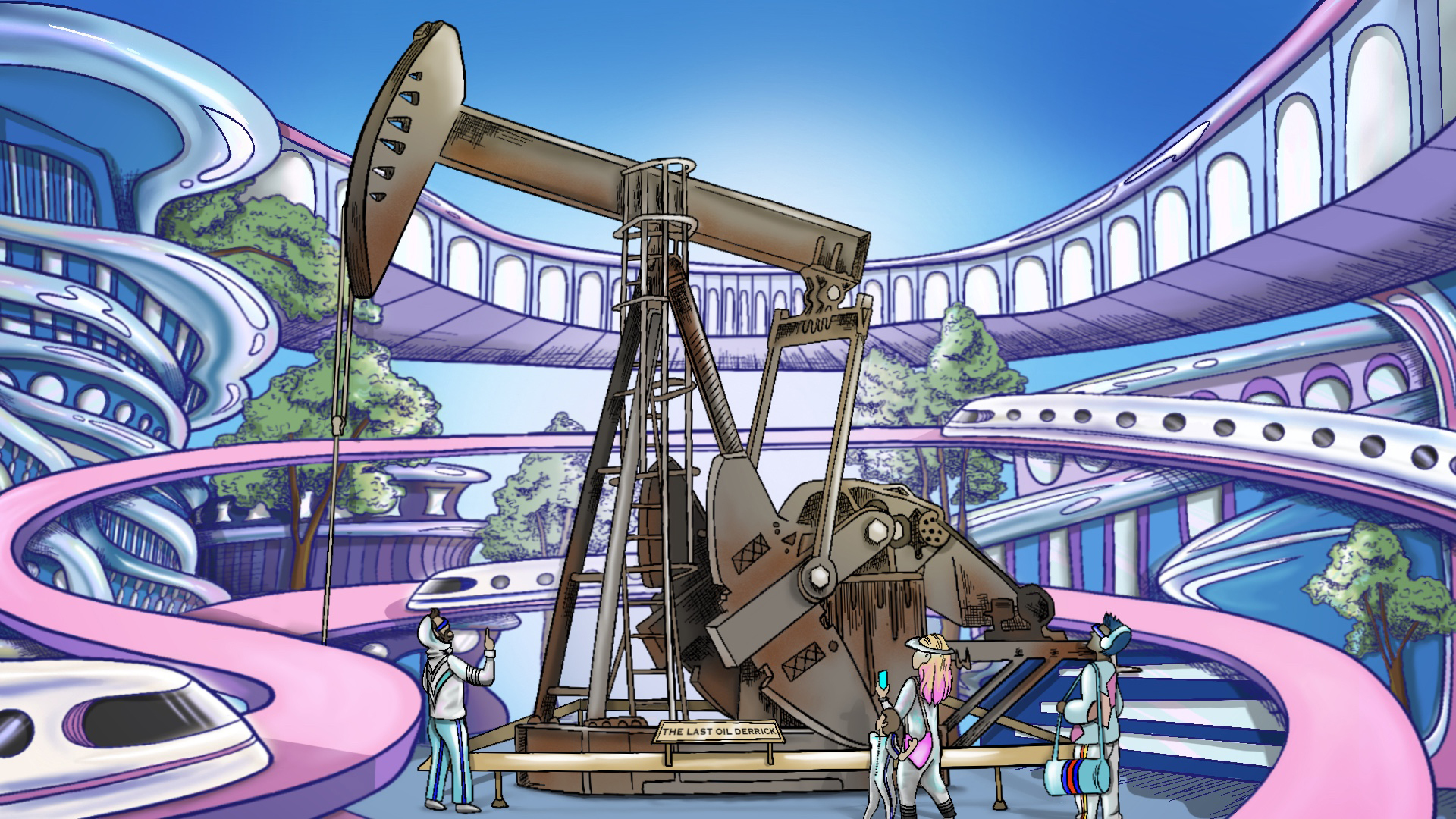

But the push for decarbonization means oil will eventually become a flash in the pan in our history. Like industrial whaling, our taste for it will dissipate until just a few small strongholds remain.

Fifty to 100 years from now, oil derricks and drilling fields in the U.S. may start to look like the abandoned mine museums and gold-rush ghost towns that litter the American West — tourist attractions that paint a picture of a lost way of life, an economy firmly in the past.

Hannah Osborne is the planet Earth and animals editor at Live Science. Prior to Live Science, she worked for several years at Newsweek as the science editor. Before this she was science editor at International Business Times U.K. Hannah holds a master's in journalism from Goldsmith's, University of London.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus