Meat eaten by city-dwelling Americans produces more CO2 than the entire UK — but there are easy ways to slash it

Halving how much edible food is thrown away, swapping beef for pork or chicken and having one meatless day a week could slash the carbon "hoofprint" of U.S. cities by up to 51%, a new study finds.

The meat consumed in U.S. cities creates the equivalent of 363 million tons (329 million metric tons) of carbon emissions per year, a new study finds.

That's more than the entire annual carbon emissions from the U.K. of 336 million tons (305 million metric tons).

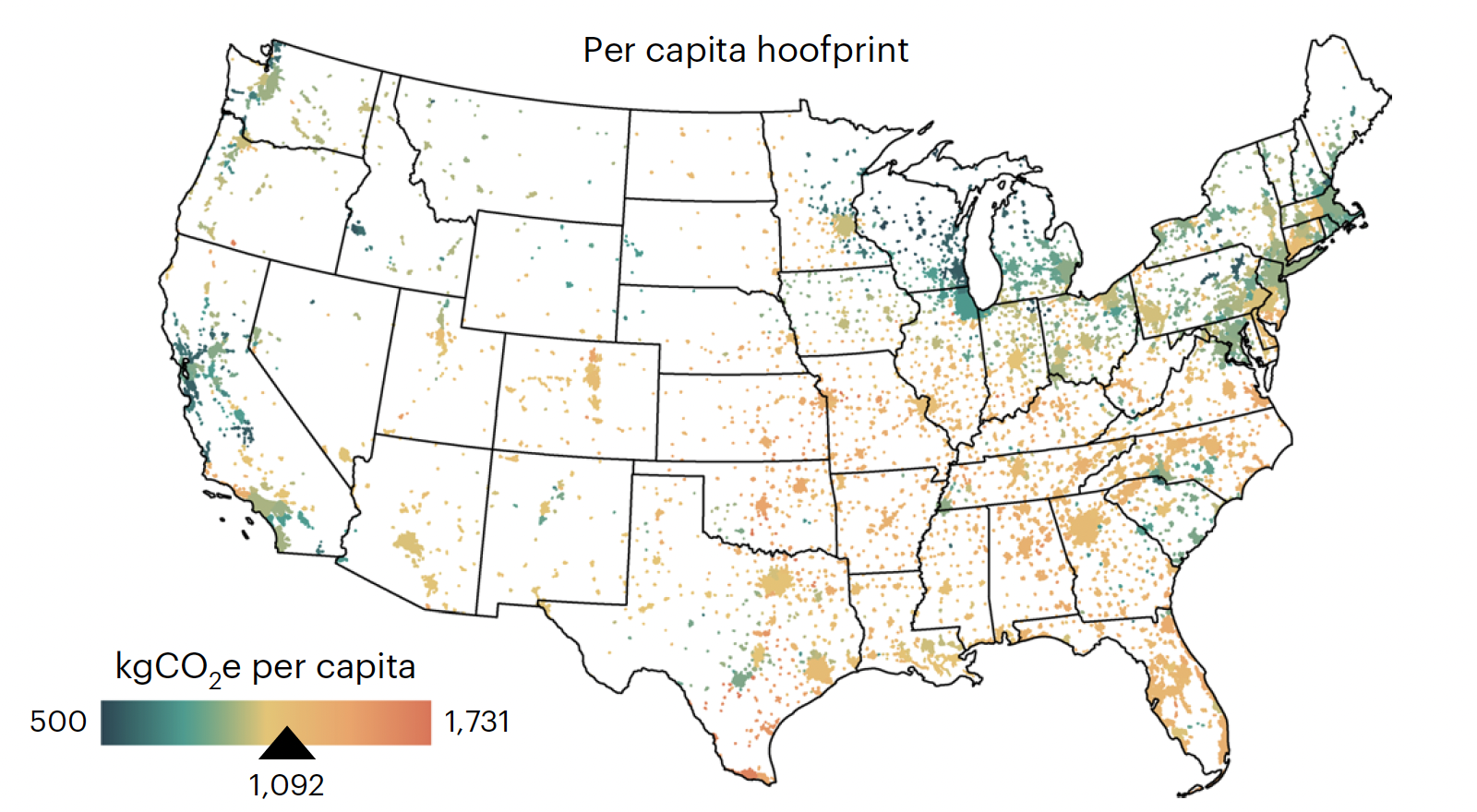

Even though city dwellers are estimated to eat roughly similar amounts of meat per person on average across the U.S., the "carbon hoofprint" — the greenhouse gas emissions from beef, pork and chicken consumption — varies substantially depending on where and how the animals are reared and processed, according to a study published Monday (Oct. 20) in the journal Nature Climate Change.

By tracing the route from where the animal feed is produced all the way to where the meat is ultimately eaten, the researchers revealed that the largest hoofprint per person — in Richmond, Missouri — is more than three times that of the smallest hoofprint per person, in Houghton, Michigan.

The amount of greenhouse gases emitted varies significantly because each city "has different sourcing geographies, and [there are] different production practices across the country," study co-author Benjamin Goldstein, an assistant professor of environment and sustainability at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, told Live Science.

Although scientists already had a good idea of the greenhouse gas footprint of meat at the regional or national level, city-level information is needed to combat these emissions, the researchers wrote in the study.

To fill this gap, the scientists developed a model, funded in part by organizations in the animal agriculture and food retail sectors, that mapped the meat supply chain for 3,531 cities in the mainland U.S., covering 93% of the U.S. population.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The team used county-level data from a national health and nutrition survey and the 2017 U.S. census to estimate the amount of meat consumed per person in each city. Then, they reconstructed the connections linking the 3,143 counties involved in animal feed production, animal husbandry and meat processing to every urban area.

They found that 5.1 million tons (4.6 million metric tons) of chicken, 4.1 million tons (3.7 million metric tons) of beef and 3 million tons (2.7 million metric tons) of pork are eaten by residents of U.S. cities every year — producing a combined carbon hoofprint of 362 million tons of carbon dioxide equivalent. This is comparable to the carbon emissions from U.S. domestic fossil fuel use, which stands at 368 million tons (334 million metric tons).

Beef production makes up 73% of the hoofprint, on average, but the contribution varies by city, depending on whether the cows graze or are in feedlots. The intensity of greenhouse gas emissions for beef varies by a factor of 4.3 across cities, while chicken varies by a factor of 4.9 and pork by 15.

Differences in feed production is the main reason for this variation, including the rates of nitrogen fertilizer application and resulting nitrous oxide emissions, the researchers wrote in the study.

Reducing or eliminating beef consumption is already recognized as important for our planet's health. This new research found that halving edible food waste, eating chicken instead of beef, and having a meatless day once a week would slash a city's carbon hoofprint by 51% — a "nontrivial" contribution toward aligning diets with the requirements of the 2015 Paris Agreement, Goldstein said.

While the study clarified the links connecting rural food producers and urban consumers, "I'd say the broad contours of what we need to do remain unchanged," Goldstein added. "There's still no such thing as a low carbon cow."

Anu Ramaswami, a professor of civil and environmental engineering at Princeton University who was not involved in the research, noted that the model the researchers developed in the study was well crafted and that revealing variation in hoofprints across cities is "very new and insightful."

Although the conclusion that beef production is the largest greenhouse gas emitter is not new, the research does highlight that individuals do not have to become vegan or vegetarian to have a meaningful impact on the carbon hoofprint, she told Live Science in an email. The proposed shift from beef to other meats is a "more viable" dietary intervention than eliminating meat altogether, Ramaswami added.

Sophie is a U.K.-based staff writer at Live Science. She covers a wide range of topics, having previously reported on research spanning from bonobo communication to the first water in the universe. Her work has also appeared in outlets including New Scientist, The Observer and BBC Wildlife, and she was shortlisted for the Association of British Science Writers' 2025 "Newcomer of the Year" award for her freelance work at New Scientist. Before becoming a science journalist, she completed a doctorate in evolutionary anthropology from the University of Oxford, where she spent four years looking at why some chimps are better at using tools than others.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus