'First species discovered on Twitter' is a parasitic fungus that dines on millipede genitals

Turns out social media is a great place for discovering parasites.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Researchers have discovered a parasitic fungus that sucks nutrients out of the reproductive organs of millipedes. They named it after Twitter.

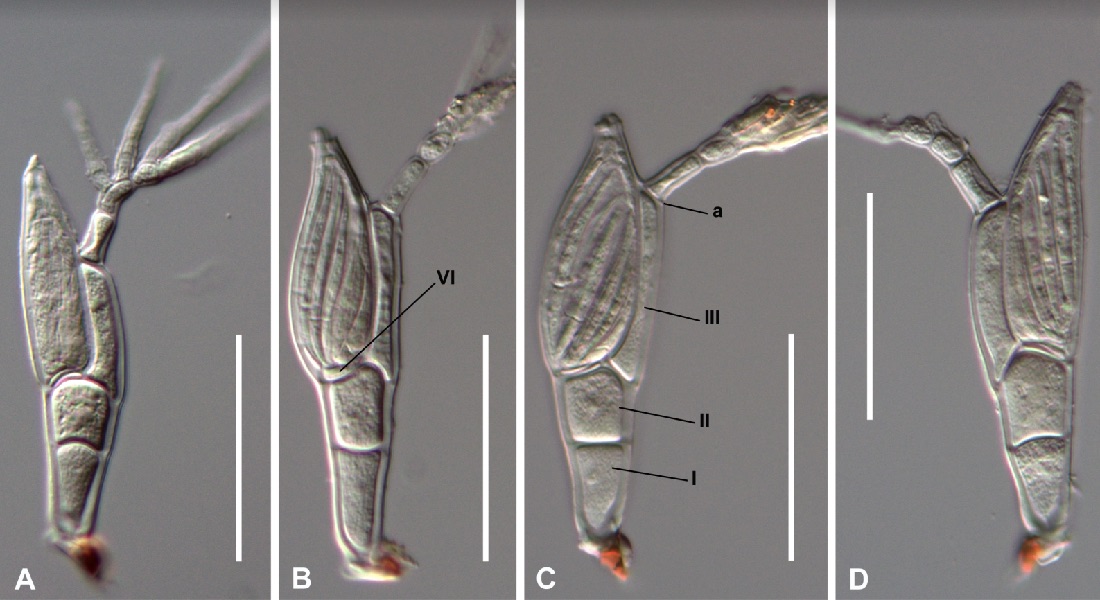

Meet Troglomyces twitteri. This near-microscopic parasite looks like a larva and is about 100 micrometers long — comparable to the average diameter of a human hair. Each spore spends its entire lifecycle hanging around the genitals of a single male or female millipede. However you may feel about Twitter, the researchers who discovered the unfortunately-placed parasite weren't trying to throw shade at the social media site when naming this newfound fungus; rather, they were paying homage to how the parasite was discovered.

According to study co-author Ana Sofia Reboleira, an entomologist at the Natural History Museum of Denmark at the University of Copenhagen, the parasite first came to her attention when she saw a colleague share a photo of a North American millipede on Twitter. Two strange, white dots flecked the millipede's exoskeleton; Reboleira instantly pegged them as parasites.

Related: 6 times parasites grossed us out in 2019

After examining several American millipede specimens in the museum's collection, Reboleira and her colleagues found more examples of the novel fungus, which nobody had ever noticed or described before.

"Until then, these fungi had never been found on American millipedes," Reboleira said in a statement. "As far as we know, this is the first time that a new species has been discovered on Twitter."

T. twitteri belongs to the insect-loving fungal order Laboulbeniales, and is one of about 30 species in the order that exclusively attack millipedes. With its head buried beneath its host's exoskeleton and its bum poking into the air, T. twitteri parasites feast on nutrients from one end, while the other prepares spores to infect their next victim. Millipede mating (an intimate affair that can resemble human mating, only with a lot more legs) provides the parasites with a perfect opportunity to spread their spores, likely explaining why the study authors so often detected them near the hosts' reproductive parts, the team wrote.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

While millipede-infecting Laboulbeniales were never seen in North America until now, they have been spotted widely around the world, including in Europe, Asia, Africa, the Middle East, Australia and New Zealand. Many of these species were only discovered in the last six years, leading Reboleira to suspect that there are many, many more of the creepy crawlies out there waiting to be discovered. It'll take a lot of retweets to find them.

The study was published May 14 in the journal MycoKeys.

- 8 Awful Parasite Infections That Will Make Your Skin Crawl

- Images: Human Parasites Under the Microscope

- The 10 most diabolical and disgusting parasites

Originally published on Live Science.

OFFER: Save 45% on 'How It Works' 'All About Space' and 'All About History'!

For a limited time, you can take out a digital subscription to any of our best-selling science magazines for just $2.38 per month, or 45% off the standard price for the first three months.

Brandon is the space / physics editor at Live Science. With more than 20 years of editorial experience, his writing has appeared in The Washington Post, Reader's Digest, CBS.com, the Richard Dawkins Foundation website and other outlets. He holds a bachelor's degree in creative writing from the University of Arizona, with minors in journalism and media arts. His interests include black holes, asteroids and comets, and the search for extraterrestrial life.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus