Fossilized brain of 525 million-year-old deep sea worm likely the oldest ever discovered

An ancient worm unearthed in China has one of the oldest fossilized brains ever found. The brain's shape could also help solve a centuries-old debate about the evolution of arthropods.

A 525 million-year-old fossilized worm unearthed in China has what is likely the oldest example of a brain ever discovered. The surprising shape of the brain offers clues about the evolution of arthropods — a group that includes insects, arachnids and crustaceans — and could help solve a mystery that's been puzzling researchers for more than a century.

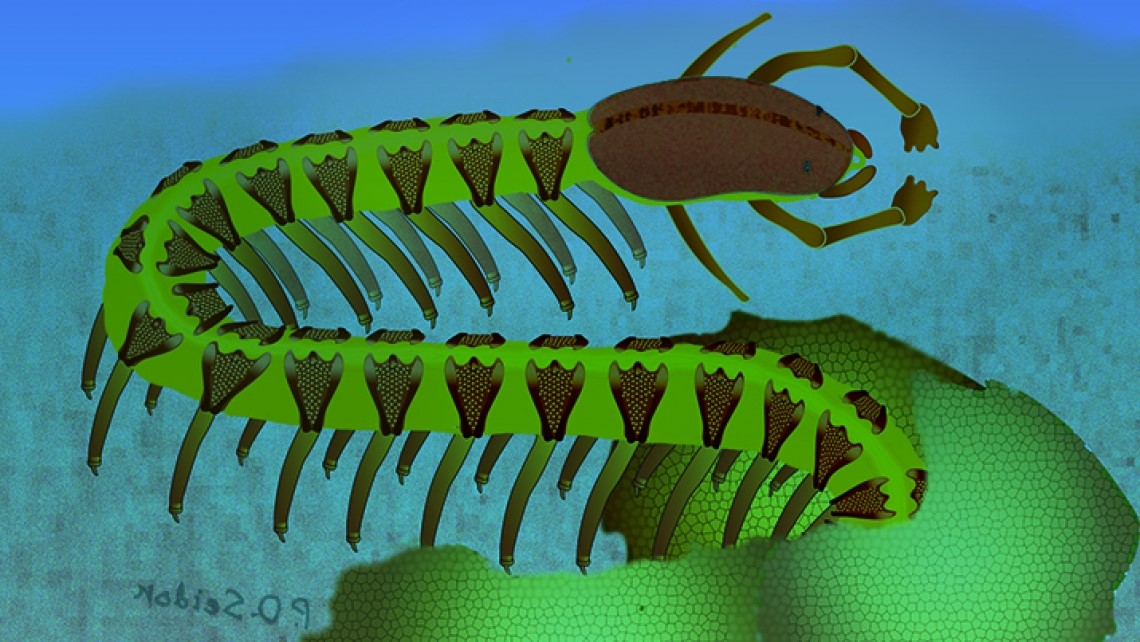

The ancient critter, known as Cardiodictyon catenulum, was discovered in 1984 along with numerous other fossils, collectively known as Chengjiang fauna, at a site in China's Yunnan province. The worm-like creature belongs to the phylum Lobopodia — a group of extinct, seafloor-dwelling arthropod ancestors with armored shells and stubby legs that were abundant during the Cambrian period (541 million to 485.4 million years ago).

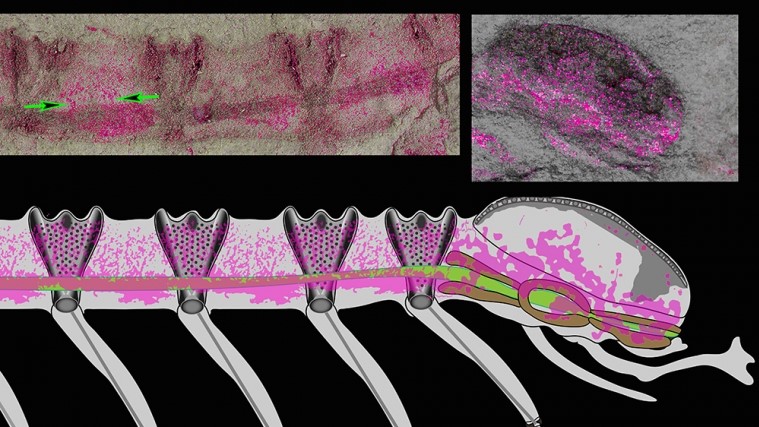

In a new study, published Nov. 24 in the journal Arthropod Evolution, another team of scientists reanalyzed the fossilized specimen and found that it had been hiding an astonishing secret — a preserved nervous system, including a brain.

"To our knowledge, this is the oldest fossilized brain we know of, so far," study lead author Nicholas Strausfeld, a neurobiologist at The University of Arizona in Tucson, said in a statement.

Related: Perfectly preserved 310-million-year-old fossilized brain found

It took almost 40 years for scientists to discover C. catenulum's brain because researchers previously believed that any soft tissue in the animal had been lost over time.

"Until very recently, the common understanding was [that] brains don't fossilize," study co-author Frank Hirth, an evolutionary neuroscientist at King's College London in the U.K., said in the statement. Due to the small size and age of the fossil, past researchers "would not even dare to look at it in hopes of finding a brain," he added.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But recent investigations of similar fossils dating to around the same time have changed this preconception. To date, primitive fossilized brains have also been found in a 500 million-year-old penis worm relative; an exceptionally well-preserved bug-like critter from around 500 million years ago; a 520 million-year-old "sea monster"; and dozens of three-eyed sea creatures dating to around 506 million years ago.

Upending arthropod evolution

As surprising as it was to find the ancient brain, the researchers were more taken aback by the shape and structure of the critter's cranium. The head and brain are both non-segmented, meaning that they are not split up into multiple parts. But, the rest of the fossil's body is divided into segments.

"This anatomy was completely unexpected," Strausfeld said. For more than a century, researchers thought that the brains and heads of long-extinct arthropods were segmented just like those of modern arthropods; most fossils of other ancient arthropod ancestors also display segmented heads and brains, he added.

Related: Ancient armored 'worm' is the Cambrian ancestor to three major animal groups

Even more surprising, C. catenulum had small clumps of nerves, known as ganglia, running through its segmented body. As a result of this discovery, the researchers believe that the segmented brains and heads seen in modern arthropods may have evolved separately from the rest of the nervous system, which likely became segmented first.

However, the study authors noted that C. catenulum's fossilized brain still shares some key characteristics with modern arthropod brains, which suggests that the "basic brain plan" has not changed too drastically in the last half-a-billion years, Strausfeld said.

The researchers next want to compare the fossilized brain with the brains of other animal groups to try and uncover more about how different brains have diversified over time.

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus