Jupiter glows in stunning new James Webb telescope images

New photos from the James Webb telescope highlight Jupiter's auroras.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Jupiter glows with polar lights and shimmering clouds in new imagery from the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST).

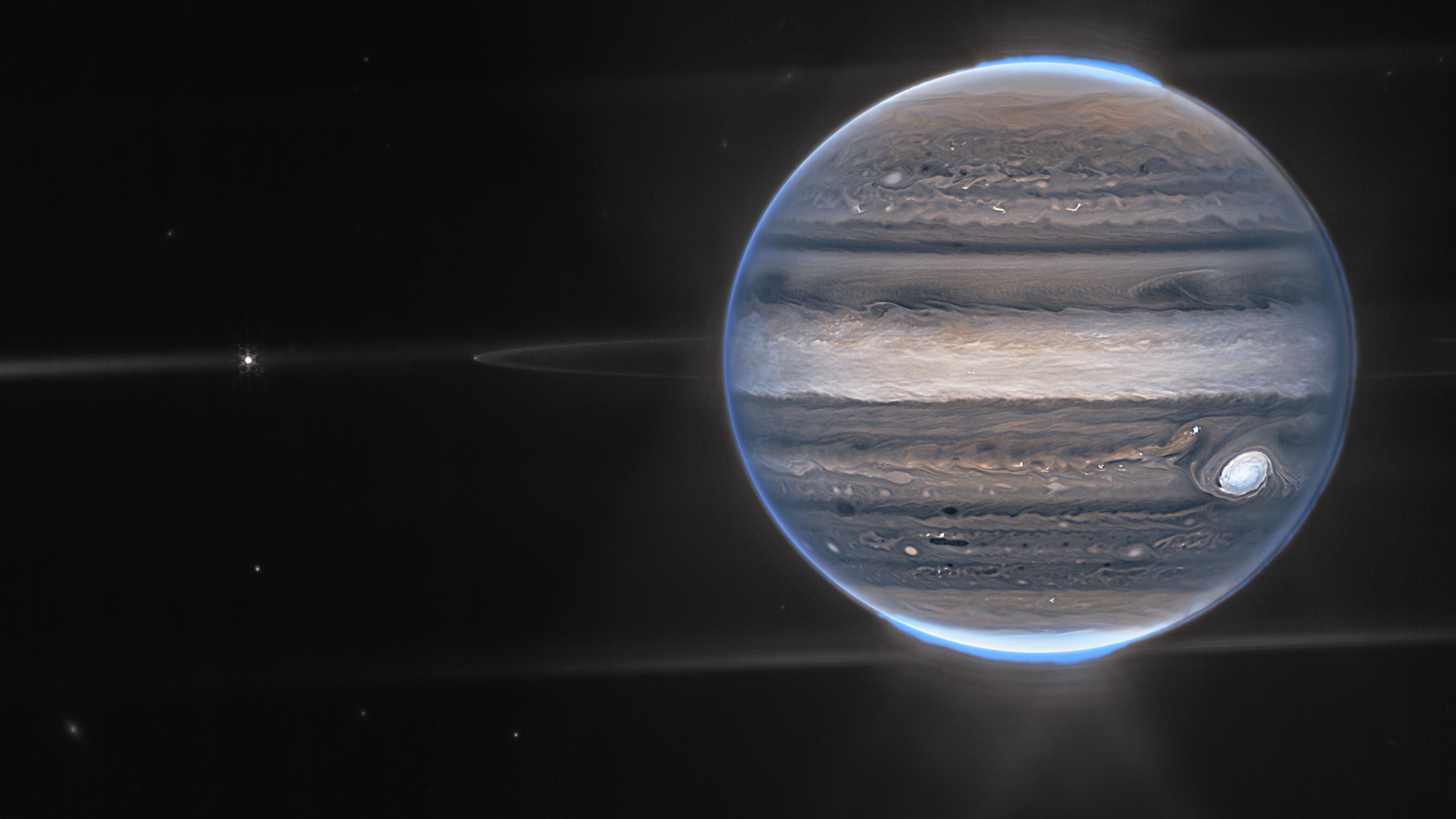

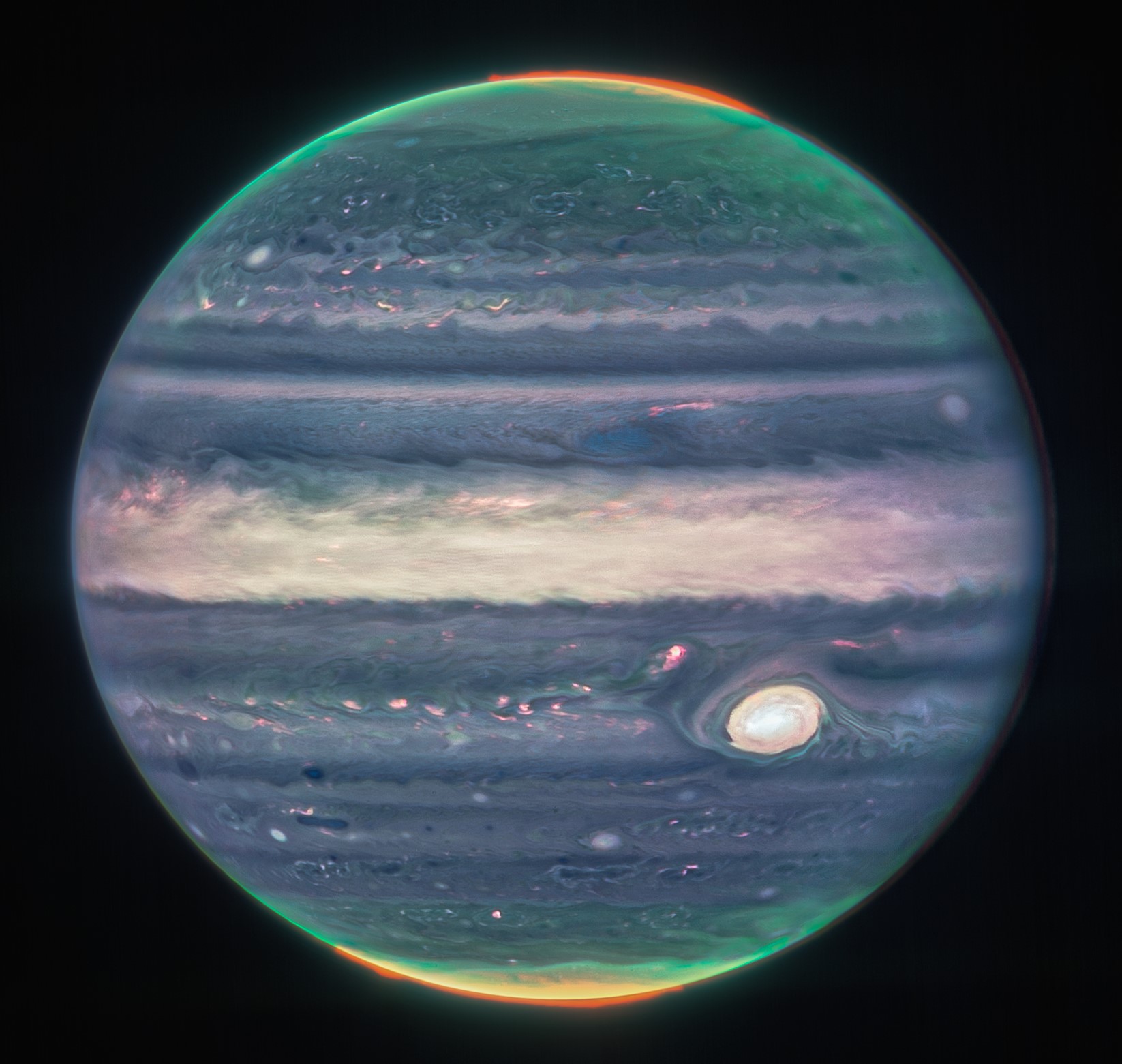

NASA released the sharp new pictures Monday (Aug. 22). The images are composites from several different wavelengths of light. In some of the new images, two of the planet's moons, Amalthea and Adrastea, sparkle in the gas giant's orbit, and Jupiter's faint rings glow like a halo. At the planet's North and South poles, the northern and southern lights glow with a pale fire.

"We hadn't really expected it to be this good, to be honest," planetary astronomer Imke de Pater, professor emerita of the University of California, Berkeley, who co-led the observations of Jupiter, said in a statement. "It's really remarkable that we can see details on Jupiter together with its rings, tiny satellites, and even galaxies in one image."

The images come courtesy of NASA's newest space-based telescope, which has already wowed the world with psychedelic images of far-flung galaxies. The JWST is operated primarily by NASA, in partnership with the European Space Agency (ESA) and Canadian Space Agency (CSA). The photos of Jupiter, part of an observation effort led by de Pater and Thierry Fouchet, a professor at the Paris Observatory, showcase what the space telescope can do closer to home.

Related reading: Jupiter, the king of planets

The Near-Infrared Camera (NIRCam) on the telescope captured the images, which were then converted to color visible to the human eye. The longest wavelengths are visible in red, while shorter wavelengths are blue. The planet's Great Red Spot, a centuries-old storm so big it could engulf Earth, appears white due to reflected sunlight, as do other high-altitude clouds. Dark lines indicate little cloud cover.

"The brightness here indicates high altitude — so the Great Red Spot has high-altitude hazes, as does the equatorial region," Heidi Hammel, Webb interdisciplinary scientist for solar system observations and vice president for science at the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy (AURA), said in the statement. "The numerous bright white 'spots' and 'streaks' are likely very high-altitude cloud tops of condensed convective storms."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Just as on Earth, particles from the sun interact with Jupiter's upper atmosphere to create light shows called auroras. These auroras are visible at both the northern and southern poles of Jupiter in the new images.

The incredible views were lined up by Judy Schmidt, a citizen scientist with no formal training in astronomy who has been processing astronomy images as a hobby for more than a decade. Because the data that comes in from telescopes like the JWST comes in the form of numbers, not pictures, image processors must translate the data to make sense to the human eye. For instance, Schmidt had to stack imagery from JWST to account for Jupiter's rapid rotation (the enormous planet does a complete rotation once every 10 hours). The result sums up the gas giant at a glance, Fouchet said in the statement.

Originally published on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus