Dangerous strep infection surging in the UK may be spreading in US

Federal health officials are investigating a potential uptick in dangerous strep infections in U.S. children.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

As U.K. health officials grapple with an ongoing surge of "invasive" strep infections in children, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) is investigating whether U.S. children are experiencing a similar uptick in infections.

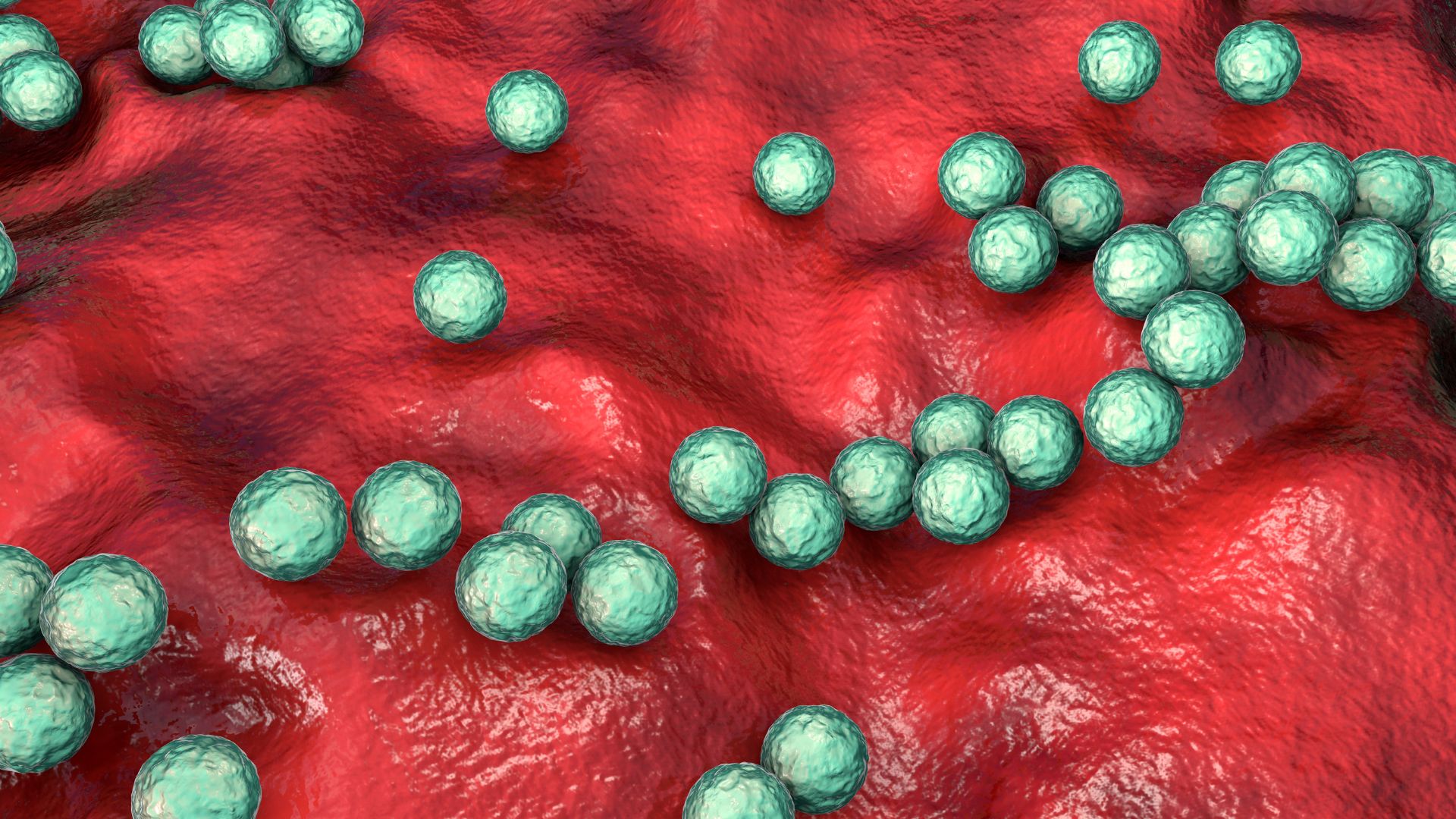

According to the agency's website, "CDC is looking into a possible increase in invasive group A strep (iGAS) infections among children in the United States." These severe infections are caused by Group A Streptococcus bacteria, the same bugs behind strep throat, an infection of the throat and tonsils; and scarlet fever, which causes a red, sandpapery skin rash.

Compared with these relatively mild ailments, invasive strep A infections occur when the bacteria spread to the blood, lungs or muscles, and can lead to life-threatening complications, according to the CDC. For example, the infections can trigger the "flesh-eating disease" necrotizing fasciitis, in which tissues rapidly die due to aggressive inflammation, and streptococcal toxic shock syndrome, a condition marked by a flood of inflammatory molecules, a dangerous drop in blood pressure and widespread organ damage.

In the U.K., the number of reported iGAS cases is higher than expected for this time of year, particularly among children, the U.K. Health Security Agency reported Dec. 15. So far in the U.K., 213 children have developed an invasive infection, 111 of whom were 1 to 4 years old. Sixteen children have died of iGAS infections so far this season in the U.K.

Related: Why flesh-eating bacteria can look like the flu

Other European countries — including France, Ireland, the Netherlands and Sweden — have reported similar infection rates among young children, the World Health Organization said.

As of Dec. 5, the CDC hadn't "heard of any notable increase" in iGAS cases in the U.S., Barbara Mahon, acting director of the agency's proposed Coronavirus and Other Respiratory Viruses Division, said at a news conference. However, since then, several children's hospitals in Arizona, Colorado, Texas and Washington have reported higher-than-average numbers of cases this season compared with the same time in past years, CNBC reported.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

As the CDC investigates these reports, the agency is encouraging children's caregivers to make sure kids are up to date on flu and chickenpox vaccinations, "since getting these infections can increase risk for getting an iGAS infection." The CDC also recommends becoming familiar with the initial signs of necrotizing fasciitis and streptococcal toxic shock syndrome:

Necrotizing fasciitis: These symptoms typically arise after an injury or surgery, as the bacteria most often enter the body through broken skin.

- A red, warm or swollen area of skin that spreads quickly

- Severe pain, including pain beyond the area of the skin that is red, warm or swollen

- Fever

Streptococcal toxic shock syndrome: After the initial symptoms below start, it usually takes about 24 to 48 hours for low blood pressure to develop. Once this happens, much more serious symptoms arise, such as tachycardia (faster than normal heart rate), tachypnea (rapid breathing) and signs of organ malfunction.

- Fever and chills

- Muscle aches

- Nausea and vomiting

- Hypotension (low blood pressure)

Caregivers should "seek medical care quickly if they think their child has one of these infections," the CDC states. Treatment involves antibiotics as well as surgery to remove infected tissues and supportive care, such as fluids, as needed.

Nicoletta Lanese is the health channel editor at Live Science and was previously a news editor and staff writer at the site. She holds a graduate certificate in science communication from UC Santa Cruz and degrees in neuroscience and dance from the University of Florida. Her work has appeared in The Scientist, Science News, the Mercury News, Mongabay and Stanford Medicine Magazine, among other outlets. Based in NYC, she also remains heavily involved in dance and performs in local choreographers' work.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus