Beat-up duck-billed dinosaur had cracked tailbones and 'cauliflower' tumor. But it just wouldn't die.

The tenacious hadrosaur lived for some time after it was injured.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

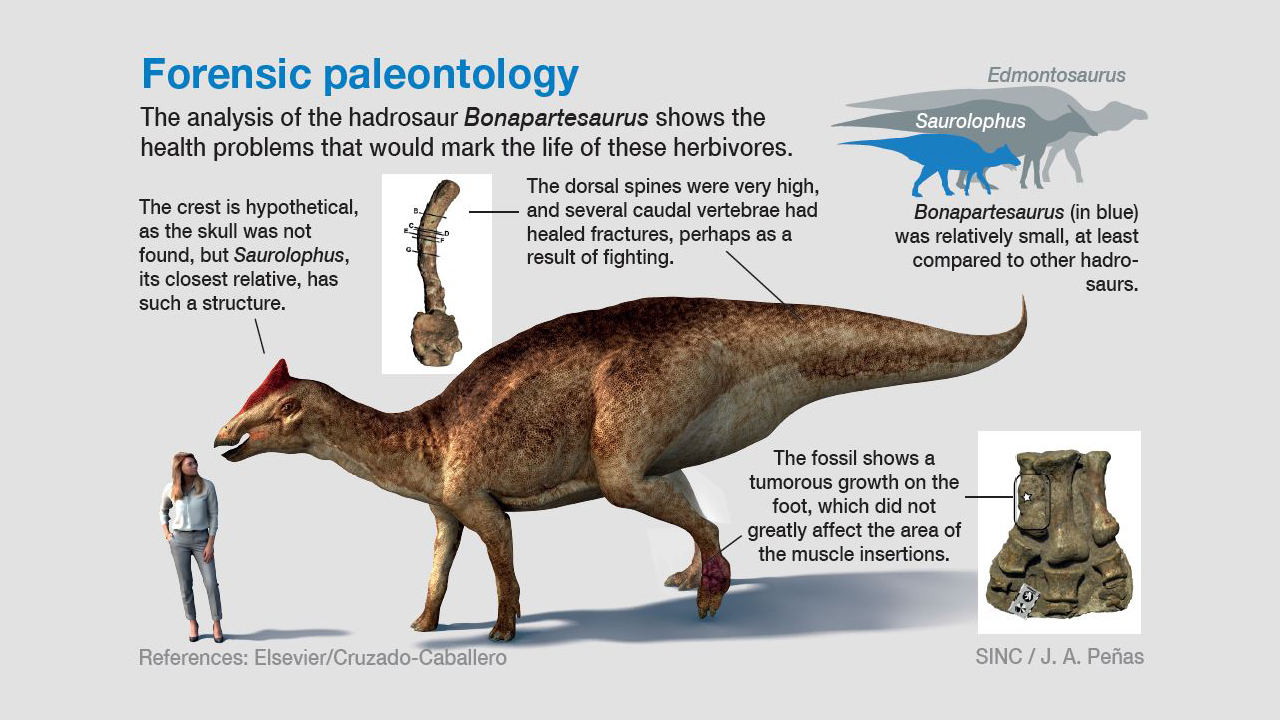

A dinosaur that lived about 70 million years ago suffered from fractured tailbones and a "cauliflower-like" foot tumor, a new fossil analysis shows.

But despite these painful maladies, the dinosaur survived for some time after it was hurt.

When late paleontologist Jaime Eduardo Powell discovered the skeleton in Argentina's Río Negro Province in the 1980s, he observed that one of the feet was injured, and he described the injury as a possible fracture. However, when researchers recently reexamined the fossil, they found that the foot deformity was instead caused by a large, possibly cancerous tumor.

Related: Photos: Digging up "Superduck," a new hadrosaur

Using computed X-ray tomography (CT) scans and microscopic analysis of bone samples, the researchers also identified fractures in two vertebrae in the middle of the dinosaur's tail, and there were erosions in the bone around the fractures that may have been caused by infections. As the fractures were partially healed, they likely weren't directly responsible for the dinosaur's death, scientists reported in a new study, published in the August 2021 issue of the journal Cretaceous Research.

"We cannot quantify how long it lived afterwards, which means that it could have lived for months or years," lead study author Penélope Cruzado-Caballero, a scientist in the Research Institute of Paleobiology and Geology for Argentina's National Scientific and Technical Research Council (CONICET), said in a statement.

Who was this beat-up dinosaur? Bonapartesaurus rionegrensis was a 30-foot-long (9-meters) hadrosaur — plant-eating dinosaurs known for their broad, ducklike mouths. Hadrosaurs were large and mostly bipedal ornithischians, or bird-hipped dinosaurs, that lived during the latter part of the Cretaceous period (about 145.5 million to 65.5 million years ago) in the Americas, Asia and Europe.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Some hadrosaur species sported ornate crests on their skulls, which may have been used for communication. Paleontologists don't know if Bonapartesaurus had a crest (the skeleton was missing its skull), but what attracted their attention was the dinosaur's left hind limb, where a large, bony overgrowth gave the foot "a cauliflower-like appearance," Cruzado-Caballero said in the statement.

The study authors found no fracture when they examined the bulging bone lump, but CT scans showed reduced bone density and ravaged bone tissue in surrounding areas, suggesting that the lump was a tumor. Dinosaurs in this group walked with most of their weight on their toes, and they had a high foot pad. This pad could have cushioned Bonapartesaurus' foot, and the injury — as dire as it appeared — might not have caused a limp, the researchers reported.

Their scans also revealed a first hint of cracks in two tail bones and subsequent infections in the surrounding bone. Fractures such as these could have happened because the hadrosaur was trampled, struck by an object, attacked by a predator, "or simply due to running stress," the scientists wrote in the study. "These are all good hypotheses, but we cannot determine which one is more likely."

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus